How Extreme Weather Is Quietly Reshaping Agricultural Trade Between U.S. States

Extreme weather events are no longer rare disruptions—they are becoming a regular stress test for agriculture in the United States. While the country remains largely self-sufficient in food production, new research shows that droughts and floods can ripple through state-to-state agricultural trade in ways that are easy to overlook but important to understand.

A recent study from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, takes a close and data-driven look at how extreme weather in one state affects agricultural output, interstate trade flows, and food manufacturing across the country. The findings reveal both vulnerabilities and a surprising degree of resilience in the U.S. agrifood system.

The Backbone of U.S. Food Security: Interstate Trade

The United States produces about 80% to 85% of the food consumed domestically, relying heavily on a complex network of farms, storage facilities, processing plants, and transportation systems. Interstate trade is a critical part of this system. Crops grown in one state often travel hundreds or even thousands of miles before being turned into food products elsewhere.

A significant share of agricultural production is not consumed directly by households. Roughly 57% of grains and 77% of livestock produced in the U.S. are used as inputs for domestic food manufacturing, while smaller portions go straight to consumers or are exported internationally. This interconnected structure means that weather shocks in one region rarely stay local.

What the Study Set Out to Do

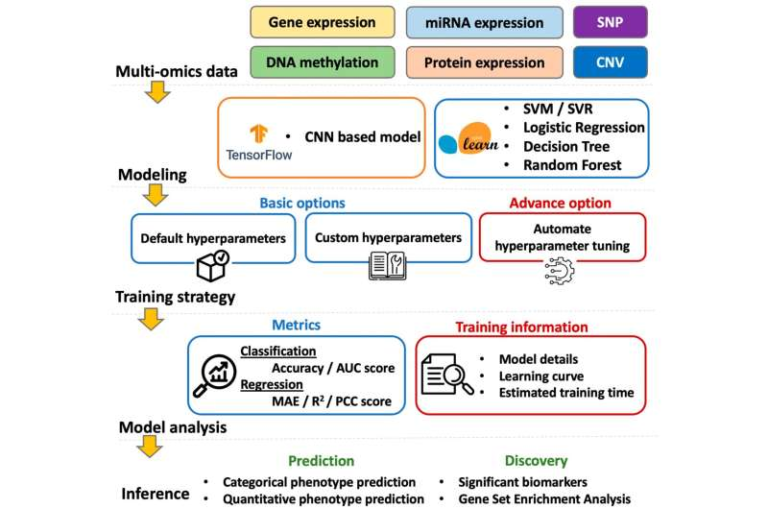

The research team, led by doctoral student Hyungsun Yim and co-authored by Sandy Dall’erba, wanted to understand something that had not been fully mapped before: how extreme weather events in a single state propagate through the national food supply chain.

To do this, the researchers combined:

- Two decades of state-to-state trade flow data from the U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics

- Detailed weather data, including temperature, precipitation, drought, and excessive wetness

- Agricultural output data across crops, livestock, fruits, and vegetables

They focused on extreme conditions such as droughts and flooding, measured using the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI), a widely used metric that captures both moisture shortages and excesses.

The 2012 Midwest Drought as a Key Example

One of the most striking case studies in the research is the 2012 drought that hit major grain-producing states in the Midwest. Under normal conditions, Iowa, Illinois, and Nebraska together account for about 34% of all grain traded domestically in the U.S.

During the 2012 drought, that share dropped sharply. Reduced grain production had immediate consequences:

- Nebraska increased imports of agricultural commodities to feed its livestock

- Texas shifted grain sourcing toward alternative suppliers such as Kansas, Oklahoma, and Louisiana

- Prices for key crops like wheat, corn, and soybeans rose by up to 20%

These price increases affected food manufacturers nationwide, illustrating how localized weather shocks can influence national food costs.

Measurable Impacts Across the Supply Chain

The study quantifies the effects of extreme weather in clear terms. On average:

- A 1% increase in drought severity in agricultural commodity–producing states leads to a 0.5% to 0.7% reduction in domestic agricultural exports

- This reduction in trade inputs causes food manufacturing output to decline by about 0.04%

At first glance, that final number may seem small. But it is precisely this modest decline that highlights an important point: the U.S. agrifood supply chain is resilient, but not invulnerable. The system absorbs shocks through trade adjustments, storage, and transportation flexibility—but those buffers have limits.

Why Food Manufacturing States Feel the Impact

Weather shocks do not only matter where crops are grown. States with large food manufacturing sectors—such as California, Texas, Illinois, and New York—can be affected even if their local weather conditions remain stable.

If grain supplies from the Midwest shrink, manufacturers elsewhere must:

- Find new suppliers

- Pay higher input prices

- Adjust production schedules or sourcing strategies

This highlights how interstate dependence is a defining feature of modern U.S. agriculture.

Transportation and Infrastructure Matter More Than Ever

A key takeaway from the research is the importance of transportation infrastructure. Railroads, highways, and river systems allow states to reroute supplies when weather disrupts production in one region.

However, as climate change increases the frequency and intensity of extreme weather, the researchers argue that infrastructure planning must adapt. Anticipating which trade corridors are most vulnerable to droughts or floods could help policymakers prioritize investments in:

- Storage facilities

- Rail and road networks

- River transportation systems

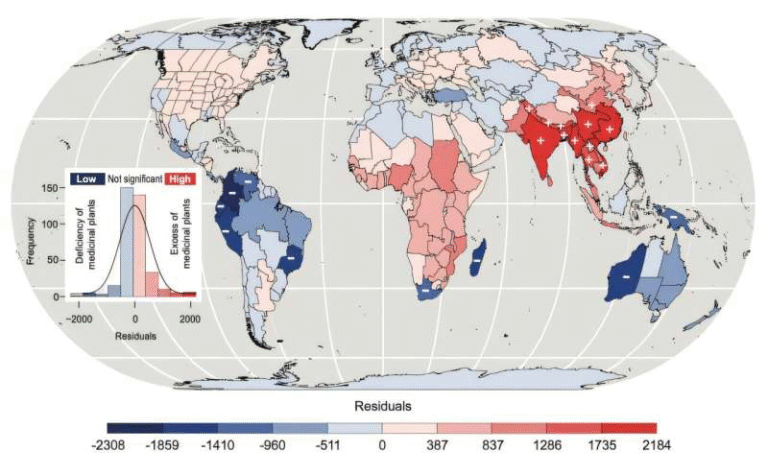

Shifting Geography of Future Agriculture

Another important insight from the study is that agricultural production is already shifting geographically. As temperatures rise, more crops are being grown:

- Further north

- At higher latitudes and elevations

- Closer to regions like the Colorado Rockies

This gradual movement is one way farmers are adapting to warming conditions, but it also means that existing trade patterns will continue to change, placing new demands on transportation and logistics systems.

Implications for Policy and Planning

The findings have practical implications beyond academic research. Understanding how weather shocks spread through the supply chain can help shape:

- Crop insurance programs

- Disaster relief policies

- State and federal investment in resilient infrastructure

The researchers emphasize that preparing for future climate shocks will require multi-state coordination, not just local planning.

A New Tool for Understanding the Food Supply Chain

To support broader use of their work, Yim and Dall’erba have developed a freely available mapping tool that visualizes the domestic agrifood supply chain at the county level. This tool allows policymakers, researchers, and the public to see how food moves across the country—and where vulnerabilities may lie.

Why This Research Matters

Climate change discussions often focus on crop yields or farm-level impacts. This study adds an important layer by showing how trade networks amplify and distribute those impacts nationwide. While the U.S. food system has proven adaptable so far, the research makes it clear that continued resilience will depend on planning, coordination, and investment.

Extreme weather may start in one field or one state, but its effects rarely stop there.

Research paper:

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2424715122