How One of the Simplest Animals Folds Itself With Origami-Like Precision

Scientists have long been fascinated by how living organisms change shape. From the folds of the human brain to the twisting of tissues during embryonic development, shape-shifting is a core feature of life. Now, new research from Stanford University’s Prakash Lab has revealed that even one of the simplest animals on Earth can perform remarkably complex folding behaviors—without a brain, muscles, or nervous system.

The study focuses on a tiny marine animal called Trichoplax adhaerens, a member of the placozoa phylum. Despite its extreme simplicity, this animal can fold and unfold its body with a precision that resembles living origami. The findings, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) in 2025, uncover a completely new type of tissue folding never observed before in nature.

A Brainless Animal That Can Change Shape

Trichoplax adhaerens is often described as one of the most primitive animals still alive today. It has no brain, no nerves, no muscles, and no organs. Its body is essentially a thin, flat sheet made up of only a few thousand cells arranged in simple layers.

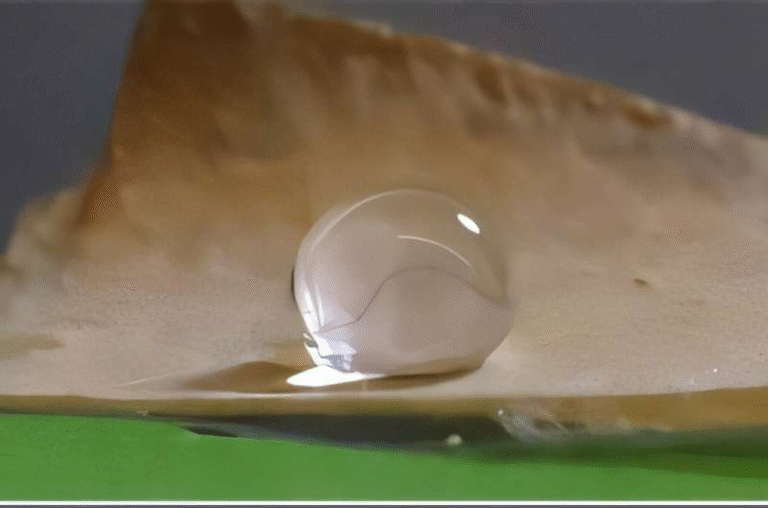

Yet, when researchers observed these animals under high-magnification live imaging, they saw something unexpected. The animals didn’t just glide along surfaces. They folded themselves into complex three-dimensional shapes, then unfolded again, repeatedly and reliably.

This behavior wasn’t random or accidental. The folding patterns were controlled, reversible, and surprisingly sophisticated for an organism with such a minimal body plan.

A New Kind of Tissue Folding

The research team, led by bioengineer Manu Prakash and graduate student Charlotte Brannon, identified this behavior as a previously unknown form of epithelial folding. Unlike tissue folding in embryos or organs, which is typically driven by changes in cell shape, growth, or genetic patterning, this mechanism works very differently.

In Trichoplax, the folding emerges from physical interactions between cells and their environment, rather than from any centralized biological control system. The animal transitions between a flat, two-dimensional sheet and folded, three-dimensional forms entirely through local cellular activity.

This discovery adds a new dimension to how scientists think about tissue organization and form in living systems.

The Surprising Role of Cilia

At the center of this discovery is a familiar cellular structure: cilia.

Cilia are tiny, hair-like projections found on the surface of many cells across plants and animals. They are usually associated with functions like moving fluids, sensing the environment, or helping cells and organisms move.

In Trichoplax adhaerens, cilia were already known to help the animal glide along surfaces. But the Stanford team discovered that cilia do much more than that.

The researchers found that the animal’s cilia can “walk” along the surface beneath it, generating localized forces that pull and bend the tissue sheet. As groups of cilia coordinate their motion, they create tension across the body, causing the flat animal to fold into ridges, valleys, and layered shapes.

This means that cilia alone are capable of shaping entire tissues, without muscles or nerves. It’s a striking example of how simple cellular components can generate complex, large-scale behavior.

Folding Without a Fixed Blueprint

One particularly interesting aspect of this folding mechanism is that it is not hard-coded or stereotyped.

In many animals, tissue folding follows strict genetic programs. The folds of the brain or the structure of organs develop in predictable, species-specific ways. Trichoplax folding, by contrast, is highly adaptable.

The exact shapes the animal forms depend on factors like surface geometry, available space, and environmental conditions. When the substrate changes, the folding patterns change as well. This makes the system flexible and responsive rather than rigidly predetermined.

Folding and unfolding can happen over seconds to minutes, showing that these shape changes are fast, dynamic, and reversible.

Visualizing Living Origami

To help communicate their findings, the researchers created a paper-based stop-motion video inspired by origami principles. The animation illustrates how simple rules of folding can generate complex forms, mirroring what happens in the living tissue of Trichoplax.

High-magnification videos included in the study show live animals folding in real time. In some images, the ventral surface of the animal is labeled with a plasma membrane stain, making the folds and transitions clearly visible.

These visuals highlight just how organized and repeatable the folding process is, even in the absence of any centralized control.

Implications for Early Animal Evolution

Beyond the immediate discovery, this research raises big questions about how shape and form evolved in early animals.

Placozoans diverged very early in animal evolution, hundreds of millions of years ago. The fact that Trichoplax can generate complex shapes using only cilia suggests that mechanical and physical principles may have played a key role in early body plans, long before the evolution of nervous systems and muscles.

Prakash and Brannon propose that basic physical interactions at the cellular level could have been enough to produce organized structures in the earliest animals. Genetic regulation and neural control may have come later, refining and stabilizing these processes.

This idea challenges traditional views that complex shape always requires complex control systems.

Why Tissue Folding Matters More Than You Think

Tissue folding isn’t just an obscure biological curiosity. It’s a fundamental process in all multicellular life.

In humans, folding helps shape the brain, allows organs to fit efficiently within the body, and plays a crucial role during embryonic development when tissues bend, merge, and separate. Errors in folding can lead to serious developmental disorders.

By revealing a minimal, physical mechanism for tissue folding, this study offers new insights into how such processes might be initiated and controlled at their most basic level.

Inspiration Beyond Biology

The implications of this work extend beyond evolutionary biology and developmental science.

Understanding how simple systems generate complex shapes could inspire new approaches in soft robotics, biomimetic materials, and self-folding structures. Engineers are increasingly interested in designs where shape change emerges from local interactions rather than centralized control—exactly what Trichoplax demonstrates so elegantly.

The idea of origami-like folding driven by microscopic forces could influence how future materials and devices are designed.

A Small Animal With Big Lessons

What makes this discovery especially compelling is its reminder that complexity doesn’t always come from complexity. Sometimes, simple rules and basic components are enough to create astonishing behavior.

By studying one of the most minimal animals known, the Prakash Lab has uncovered principles that may apply across biology, from the earliest animals to modern humans—and possibly beyond biology altogether.

Research paper:

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2517741122