How University of Missouri Researchers Are Helping Farmers Prevent Livestock Losses Through Smarter Composting and Biosecurity

Farmers have a tough job. They juggle feeding animals, managing crops, handling machinery, and dealing with endless paperwork. But one often overlooked responsibility is the disposal of dead livestock—a sensitive but essential task for maintaining animal health and preventing disease outbreaks. Recently, researchers from the University of Missouri (MU) have been leading the charge in helping farmers across the state handle this problem more safely and efficiently through livestock mortality composting and biosecurity education.

The Core Problem: What Happens When Animals Die on a Farm

Every livestock operation, whether it’s a poultry farm or a cattle ranch, will face animal deaths. Leaving carcasses unattended or disposing of them improperly can allow disease pathogens to spread, endangering entire herds or flocks. Common methods like burial or rendering can be costly, environmentally risky, or logistically challenging.

This is where composting comes in as a practical and eco-friendly solution. When done correctly, composting not only breaks down carcasses safely but also creates nutrient-rich material that can be reused to enrich soil. However, it’s not as simple as throwing a carcass in a pile and waiting for nature to do its job. It requires knowledge of temperature control, carbon-nitrogen balance, and moisture management—and that’s where MU’s research and workshops step in.

The Missouri Approach: Science Meets Practical Training

The University of Missouri Extension, in collaboration with the Missouri Department of Agriculture and the Missouri Department of Natural Resources, has been working for over a decade to educate farmers about best practices for animal mortality management. Under the leadership of Teng-Teeh Lim, an extension professor in the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources, and graduate student Rana Das, the team has taken their research directly to the people who need it most—farmers.

They have conducted hands-on workshops across Missouri, teaching participants how to build and maintain compost piles that can safely decompose carcasses without spreading disease. Farmers get to see firsthand how specific materials—wood chips, sawdust, and old compost—play a role in achieving the right decomposition balance.

The secret to safe composting, according to the MU team, is maintaining the internal compost pile temperature at 131°F (55°C) for at least three consecutive days. At this level, most pathogens are destroyed, ensuring the composted material poses no disease risk.

What the Research Found

The findings from this work are published in the journal Compost Science & Utilization, in a paper titled “Enhancing On-Farm Biosecurity Education and Mortality Composting Practices in Missouri, USA.” The study highlights how controlled composting using specific carbon sources—like wood chips and sawdust mixed with nitrogen-rich material—leads to effective carcass breakdown.

At MU’s Beef Research & Teaching Farm, researchers tested several compost piles built under different conditions. Their goal was to find the most efficient combination of carbon materials, moisture levels, and layering techniques. The results showed that with proper management, composting could completely decompose carcasses while neutralizing harmful bacteria and viruses.

Farmers who attended these workshops expressed strong interest in understanding the finer details—such as carbon-to-nitrogen ratios and optimal moisture content—and were eager to apply what they learned to their own operations.

Beyond Composting: Strengthening Farm Biosecurity

The workshops weren’t just about composting; they also introduced farmers to broader biosecurity measures through MU Extension’s Biosecurity Outreach Program. This program uses a mobile biosecurity trailer to demonstrate the Danish Entry System, a strict hygiene protocol used internationally in livestock farming.

This system involves creating clear “clean” and “dirty” zones on a farm to prevent cross-contamination. Farmers are shown how simple steps—like hand sanitizing, wearing dedicated footwear and clothing, and following structured entry procedures—can significantly reduce the risk of bringing outside pathogens into barns or livestock areas.

According to MU Extension, this educational outreach has been well received. Farmers appreciate seeing the concepts in action rather than just reading about them. The visual and interactive learning helps them understand how small behavioral changes can have big impacts on herd health.

Why This Matters for Animal Health and Food Security

When disease outbreaks like avian influenza or porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strike, they can devastate livestock populations and cripple rural economies. Preventing such events starts with on-farm practices that reduce disease exposure. MU’s research and extension programs provide farmers with tools to prevent outbreaks instead of reacting to them.

Proper carcass disposal is more than just a sanitation measure—it’s a biosecurity safeguard that protects not only individual farms but the broader food supply chain. Composting, when performed correctly, is sustainable, cost-effective, and environmentally responsible compared to alternatives like incineration or landfilling.

Additionally, the resulting compost can be used to improve soil structure, fertility, and microbial health—closing the loop between animal agriculture and sustainable farming.

The Science Behind Livestock Composting

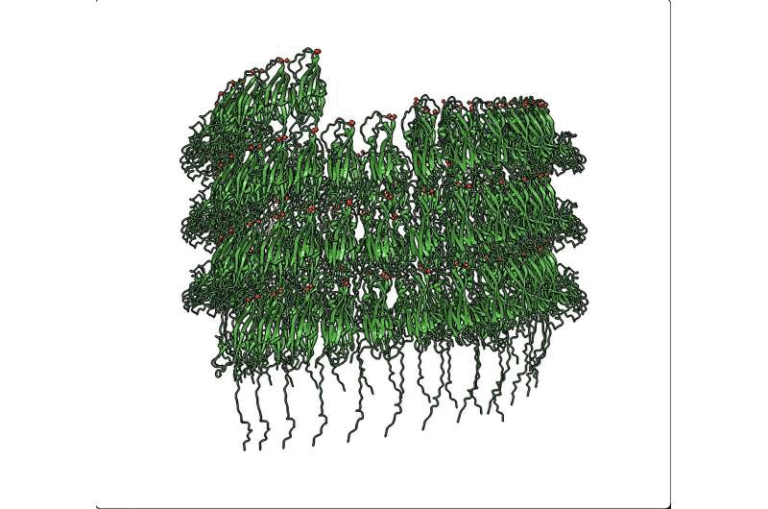

Composting livestock mortalities works on the same biological principles as composting leaves or food waste, just on a larger and more controlled scale. Microorganisms—mainly bacteria and fungi—break down the organic matter, generating heat as a byproduct.

The key stages include:

- Initial heating (mesophilic stage): Microbes begin decomposition, raising pile temperature.

- Thermophilic stage: Temperatures climb above 131°F, killing pathogens and speeding decay.

- Cooling and curing stage: The compost stabilizes, with beneficial microbes converting remaining material into humus.

The carbon-to-nitrogen ratio (C:N ratio) plays a crucial role. Too much nitrogen (from carcasses) leads to odor and ammonia loss, while too much carbon (from sawdust or wood chips) slows decomposition. The ideal C:N ratio for carcass composting typically falls between 25:1 and 30:1.

Maintaining moisture levels of 40–60% ensures microbial activity continues effectively. Farmers are taught to monitor pile temperatures and moisture using simple tools like compost thermometers and hand-squeeze tests.

Missouri’s Model for Other States

Missouri’s program has become a template for other regions facing livestock disposal challenges. States that deal with frequent disease outbreaks or mass mortality events can learn from MU’s data-driven, community-oriented approach.

The combination of research, extension education, and government collaboration makes the initiative particularly strong. By giving farmers both the science and the hands-on skills, it bridges the gap between theory and practice.

Moreover, the outreach model—bringing knowledge to rural communities through mobile demonstrations—shows how agricultural universities can make research directly beneficial to real-world farming problems.

The Bigger Picture: Why Biosecurity Awareness Matters More Than Ever

Biosecurity isn’t just about preventing large-scale epidemics; it’s about protecting everyday farm operations from invisible threats. Diseases can spread through contaminated footwear, shared equipment, feed trucks, or even visitors.

Simple steps—like separating animal groups, cleaning tools regularly, and limiting access to animal areas—can drastically reduce disease risks. The Danish Entry System demonstrated by MU is a proven way to establish a physical and behavioral barrier between potential contaminants and livestock.

As global trade and climate variability continue to increase disease pressures, education and preparedness become essential for farmers everywhere. What MU is doing in Missouri is not just helping local producers—it’s contributing to the broader resilience of animal agriculture.

Final Thoughts

The University of Missouri’s composting and biosecurity initiative is a perfect example of applied agricultural science making a tangible difference. By combining research, education, and community outreach, MU is helping farmers across Missouri prevent livestock losses, strengthen farm hygiene, and promote sustainable practices.

These workshops are more than just training sessions—they’re shaping the next generation of resilient, environmentally responsible, and health-conscious farming.

Research Reference: Enhancing On-Farm Biosecurity Education and Mortality Composting Practices in Missouri, USA – Compost Science & Utilization (2025)