How Virus Social Interactions Can Shape the Success or Failure of Antiviral Drugs

Scientists have long known that viruses mutate quickly, but new research suggests something even more intriguing: viruses don’t act alone. Inside infected cells, they can interact, cooperate, and even undermine one another. A new study from researchers at the University of Washington School of Medicine shows that these viral “social behaviors” can directly influence how effective antiviral drugs are—and, in some cases, help explain why promising treatments fail in real-world clinical trials.

The research focuses on poliovirus and an experimental antiviral drug called pocapavir, offering fresh insight into the complex relationship between viral evolution, population dynamics, and drug resistance.

The Hidden Social Lives of Viruses

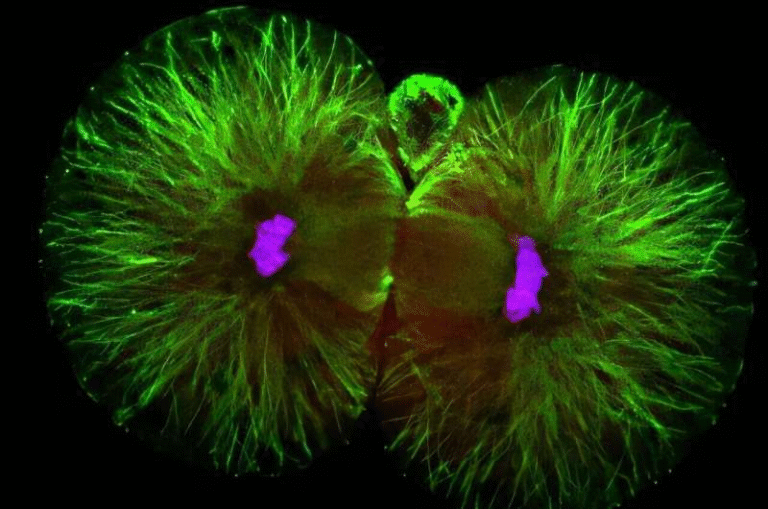

Viruses are often portrayed as solitary invaders: a single virus enters a cell, hijacks its machinery, and produces copies of itself. In reality, infected cells are frequently invaded by multiple virus particles at the same time, a phenomenon known as coinfection.

When coinfection happens, viruses share the same intracellular environment. This allows them to interact in ways that resemble cooperation or competition. They may share proteins, interfere with one another’s replication, or collectively influence how well they survive under stressful conditions—such as exposure to antiviral drugs.

According to this new study, these interactions are not just biological curiosities. They can be central to whether a drug works or fails.

Who Conducted the Study and Why It Matters

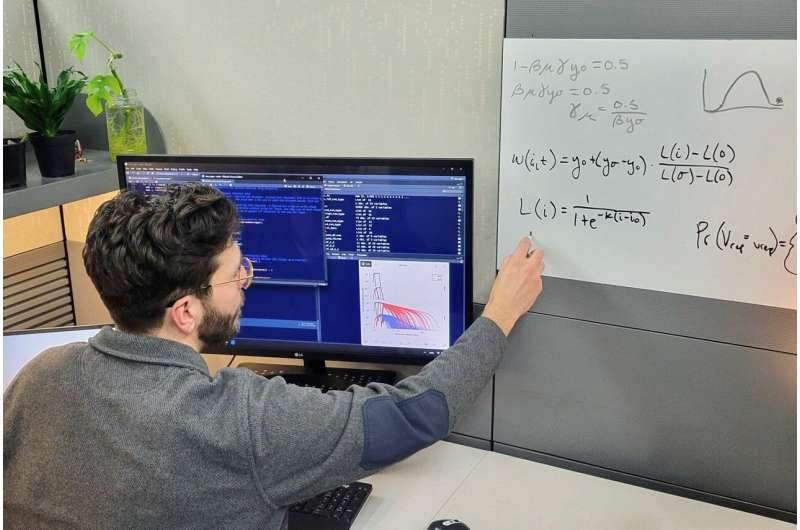

The research was led by Alexander J. Robertson, a Ph.D. student in the Molecular & Cellular Biology program at the University of Washington. Robertson studies how antimicrobial resistance evolves, especially in situations where microbes—or in this case, viruses—must interact with one another.

He worked under the mentorship of Alison Feder, an assistant professor of genome sciences whose lab studies rapid pathogen evolution, and Benjamin Kerr, a professor of biology known for combining mathematics, computer simulations, and experiments to explore evolutionary biology.

Their findings were published in Nature Ecology & Evolution, a leading journal that focuses on how ecological and evolutionary forces shape life.

Why Poliovirus Is Still a Global Concern

Poliovirus may seem like a problem of the past, thanks to widespread vaccination campaigns. However, the virus has not been fully eradicated. New cases continue to appear, particularly in Pakistan and Afghanistan, according to the World Health Organization.

This ongoing risk highlights the need for effective antiviral treatments, especially for immunocompromised individuals or in outbreak scenarios where vaccines alone may not be enough.

Pocapavir emerged as one of the most promising antiviral candidates against poliovirus, making its disappointing performance in clinical trials a serious puzzle.

Pocapavir: Promising in the Lab, Problematic in People

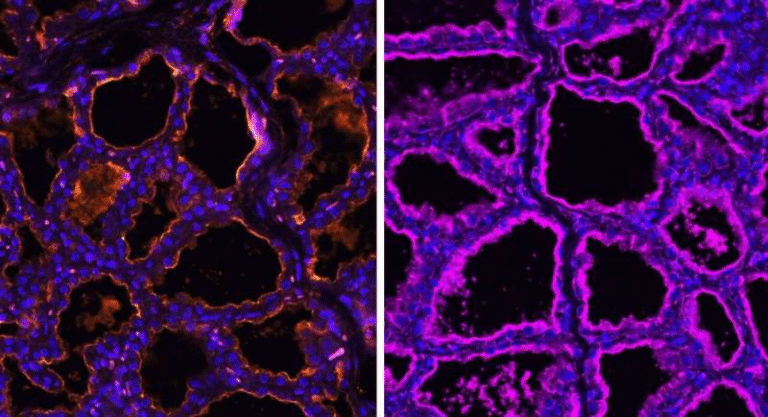

In laboratory cell cultures, pocapavir appeared highly effective. The drug targets the poliovirus capsid—the protein shell surrounding the virus’s genetic material—making it harder for the virus to replicate.

Even more interestingly, earlier experiments suggested that drug-susceptible viruses could help suppress drug-resistant ones. When both types infected the same cell, susceptible viruses produced functional proteins that resistant viruses depended on, effectively sensitizing resistant viruses to the drug.

Yet when pocapavir was tested in human clinical trials, resistance emerged rapidly, and the drug failed to deliver lasting benefits.

This contradiction between lab success and clinical failure prompted researchers to ask a deeper question: what changes between the petri dish and the human body?

The Role of Viral Population Density

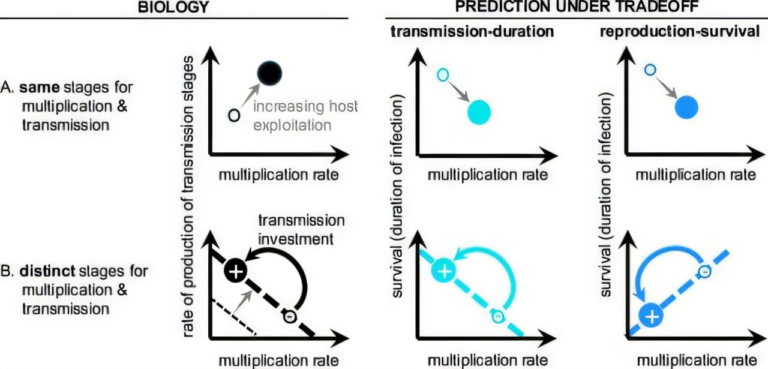

The UW researchers developed a mathematical model to explore how viral populations behave over time under drug treatment. Their key discovery was surprisingly counterintuitive.

At the start of treatment, when the viral population is dense, many virus particles infect the same cells. Under these conditions, coinfection is common, and interactions between susceptible and resistant viruses allow pocapavir to work as intended.

However, pocapavir is a potent drug. As treatment continues, it rapidly reduces the overall number of viruses. While this sounds like success, it has an unintended side effect: fewer viruses means fewer coinfections.

Once the viral population becomes sparse, resistant viruses are more likely to infect cells on their own, without susceptible viruses present. Without those interactions, resistant viruses no longer benefit from shared resources—and crucially, they are no longer suppressed by susceptible ones. This creates ideal conditions for resistant strains to take over.

Why Less Potent Treatment Might Sometimes Be Better

One of the most striking conclusions of the study is that stronger is not always better when it comes to antiviral drugs that rely on viral interactions.

The researchers showed that lowering the potency of pocapavir—at least in theory—could help maintain a population of susceptible viruses long enough to keep interacting with resistant ones. This continued interaction could slow or prevent the rise of resistance, even if the infection takes longer to clear.

This does not mean patients should receive weaker drugs or lower doses without careful testing. Instead, it highlights a trade-off in antiviral strategy:

- Aggressive treatment may clear infections quickly but allow resistance to emerge.

- A more measured approach may take longer but reduce the risk of resistant strains spreading.

Eco-Evolutionary Feedback Inside the Body

The study emphasizes a concept known as eco-evolutionary feedback, where ecological factors (like population size and density) influence evolutionary outcomes (like resistance), which then loop back to affect the ecology of the system.

In this case, drug treatment changes viral population density, which alters how viruses interact, which then shapes how resistance evolves. It’s a feedback loop happening at the microscopic level, inside individual cells.

Understanding these dynamics could help researchers design smarter antiviral therapies that account not just for how drugs attack viruses, but how viruses respond as populations.

Why This Research Goes Beyond Poliovirus

While the study focuses on poliovirus, its implications extend much further. Many viruses—including influenza, HIV, and SARS-CoV-2—frequently infect cells in groups rather than alone.

If viral social interactions influence drug resistance in poliovirus, similar mechanisms may be at play in other viral infections. This could help explain why some antiviral treatments lose effectiveness over time and why resistance evolves so quickly in certain diseases.

Rethinking Antiviral Drug Design

The findings suggest that future antiviral development may need to consider how drugs affect viral populations as communities, not just as individual particles. Dosing strategies, combination therapies, and treatment timing could all be optimized to preserve beneficial viral interactions that suppress resistance.

While these insights are not immediate clinical recommendations, they offer a powerful framework for rethinking how we fight viral diseases in an era of rapid evolution.

Research Paper Reference:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-025-02926-x