Hydrogel Cilia Set a New Standard in Microrobotics and Low-Voltage Microactuation

Cilia are micrometer-scale, hair-like structures found throughout nature, and despite their tiny size, they play critical roles in the human body. From helping clear mucus out of the lungs to guiding brain development and transporting reproductive cells, their fast, coordinated, three-dimensional beating motion is essential for life. Now, researchers have taken a major step toward replicating this natural marvel using engineering, creating artificial hydrogel cilia that closely match real biological ones in size, speed, and motion.

A collaborative team of scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems (MPI-IS) in Stuttgart, The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, and Koç University in Istanbul has developed micrometer-scale hydrogel cilia that can be precisely controlled using extremely low electrical voltages. Their work, published in the journal Nature, is titled 3D-printed low-voltage-driven ciliary hydrogel microactuators, and it represents a significant milestone in microrobotics, soft robotics, and bioinspired engineering.

Why Cilia Matter in Biology

In nature, cilia are everywhere. In the human brain, their motion is vital for proper neuronal development. In the respiratory system, cilia beat rhythmically to clear dust, bacteria, and mucus from the airways. In the reproductive system, they help transport gametes. When cilia fail to function properly, the consequences can be severe, leading to neurodevelopmental disorders, chronic respiratory diseases, infertility, and embryonic malformations.

Despite their importance, studying real cilia in action has always been difficult. Biological cilia are fragile, tiny, and difficult to manipulate individually. Until now, scientists could mostly observe them passively. This new artificial system changes that.

Artificial Cilia That Match Nature in Scale

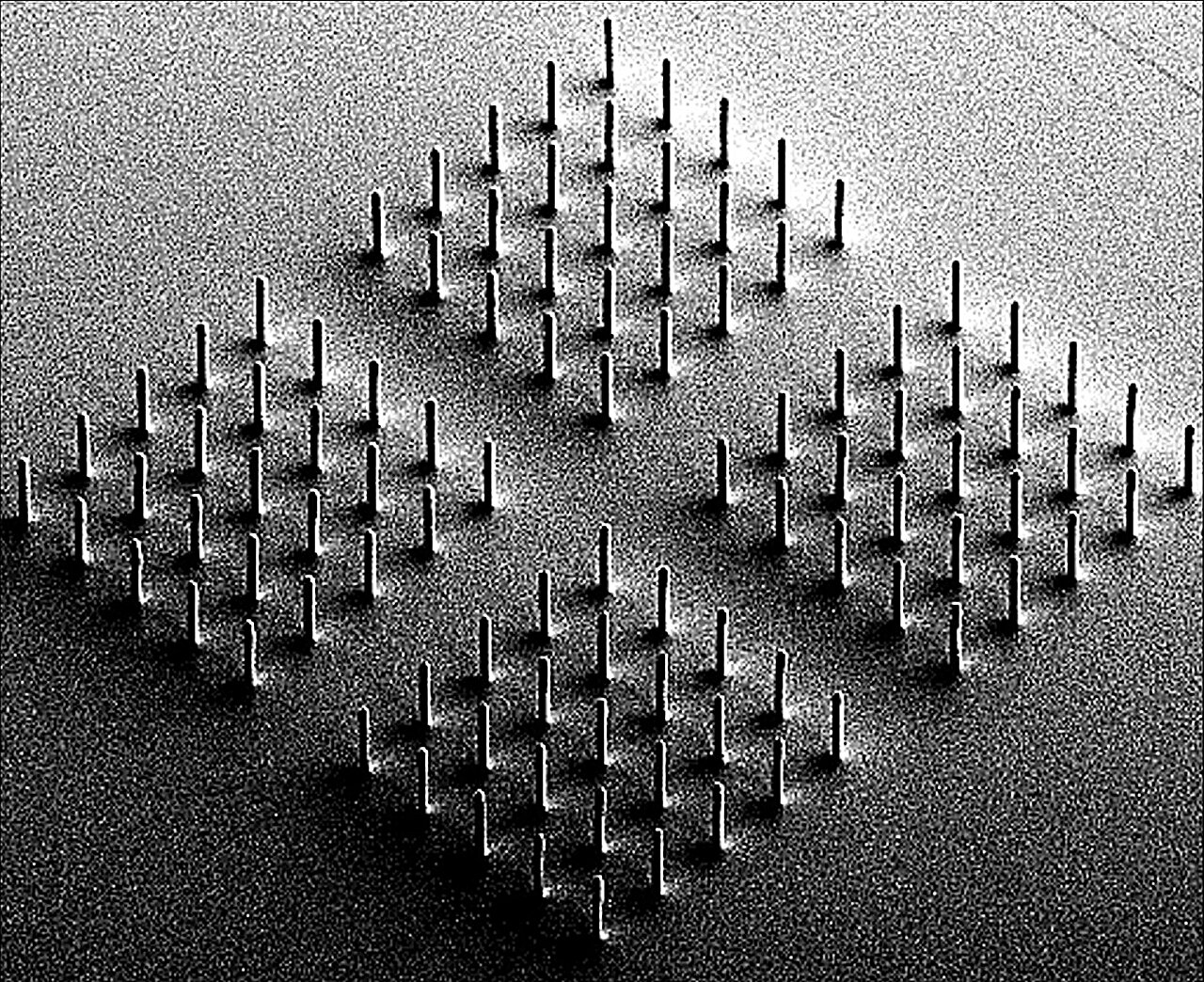

Each artificial hydrogel cilium developed in this research measures approximately 18 micrometers in length and around 2 micrometers in diameter, making them nearly identical in size to natural cilia. Hundreds of these microactuators are arranged on a flexible, foil-like substrate that contains integrated microscopic electrodes.

Because the structures are far too small to be seen with conventional optical microscopes, researchers used Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to visualize their fine details. The images reveal highly uniform, precisely fabricated microstructures with remarkable consistency across large arrays.

How the Hydrogel Cilia Move

The motion of these artificial cilia is driven by ion migration inside a soft hydrogel, controlled by an external electric field. Around each individual cilium, researchers placed four tiny electrodes. When activated, these electrodes generate an electric field that causes ions within the hydrogel to move, dragging water molecules with them. This internal movement leads to bending, twisting, or rotating motion of the cilium.

By selectively powering different electrodes, scientists can control both the direction and type of motion:

- Activating electrodes on one side causes the cilium to bend toward that side

- Activating the electrodes in a timed sequence causes the ions to move in a circular path, resulting in smooth, three-dimensional rotation

This allows the artificial cilia to reproduce the high-frequency, 3D beating motions seen in real biological systems, typically ranging from 5 to 40 hertz.

Extremely Low Voltage, High Performance

One of the most impressive aspects of this work is the low voltage required to drive the system. The hydrogel cilia operate at just 1.5 volts, which is below the electrolysis threshold in water. This means the system does not produce harmful chemical reactions and is considered safe for use in biological environments, including potential applications inside the human body.

This low-voltage actuation is inspired by how muscles work in living organisms, where electrical signals control ion distribution to generate motion. By translating this principle into a micrometer-scale hydrogel system, the researchers achieved fast, efficient, and biologically compatible actuation.

Advanced Fabrication Using 3D Printing

To build these structures, the team used Two-Photon Polymerization (2PP), a high-resolution 3D printing technique capable of producing features at the nanometer scale. The hydrogel cilia are printed layer by layer, allowing precise control over their internal network structure.

The hydrogel contains nanometer-scale pores, which act like tiny highways for fluid and ion movement. These pores dramatically increase how quickly ions and water can move through the material, resulting in rapid response times and strong actuation, even at low voltages.

Durability and Performance in Real Fluids

The researchers extensively tested the durability of their artificial cilia. Each structure was actuated more than 330,000 times, showing almost no signs of wear or performance degradation. This corresponds to roughly a full day of continuous beating at 5 hertz, similar to the natural operational lifespan of real cilia.

Importantly, the hydrogel cilia were also shown to function in biologically relevant fluids, including human serum and mouse plasma. This demonstrates their robustness and reinforces their potential for medical and biomedical applications.

A New Platform for Studying Cilia Behavior

Beyond engineering, this technology offers something biology has long needed: a controllable, programmable platform for studying cilia dynamics. Researchers can now explore how cilia move individually, how they coordinate in groups, and how their collective motion affects fluid transport and mixing.

This opens the door to deeper investigations into developmental biology, sensory processes, and disease mechanisms related to ciliary function. Instead of simply observing natural cilia, scientists can now actively test hypotheses using artificial systems.

Future Applications in Medicine and Microrobotics

The implications of this research extend far beyond the lab. In the future, soft, controllable hydrogel cilia could inspire medical devices designed to replace or assist damaged cilia in patients with respiratory, reproductive, or neurological disorders.

From an engineering perspective, the work establishes a foundation for next-generation microrobots, microfluidic systems, and soft microdevices. The combination of fast response, low power consumption, and precise control makes these actuators ideal for applications where traditional mechanical systems fail.

The team even demonstrated a flapping micromachine, showing how these cilia can be integrated into larger microrobotic systems capable of complex motion.

Why This Research Stands Out

Previous artificial cilia systems often relied on magnetic fields, optical stimulation, or bulky external setups, which limited their speed, scalability, or compatibility with biological environments. This hydrogel-based, electrically driven approach offers a more natural, efficient, and scalable solution, closely mirroring how living systems generate motion.

By combining materials science, microfabrication, and bioinspired design, this research sets a new benchmark for what is possible in microscale actuation.

Research paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09944-6