Long-Term Pesticide Exposure Accelerates Aging and Shortens Lifespan in Fish, New Study Finds

Long-term exposure to low levels of a widely used agricultural pesticide can speed up biological aging and significantly shorten the lifespan of fish, according to new research led by a biologist from the University of Notre Dame. The findings add to growing concerns that chemicals considered “safe” at low concentrations may still cause serious harm over time—damage that standard toxicity tests often fail to detect.

The study focuses on chlorpyrifos, a common insecticide that has been used globally for decades. While the chemical is known to cause acute toxicity at high doses, this research shows that chronic, low-dose exposure can quietly accelerate aging at the cellular level, leading to earlier death without obvious short-term symptoms.

How the Research Began: Field Studies in China

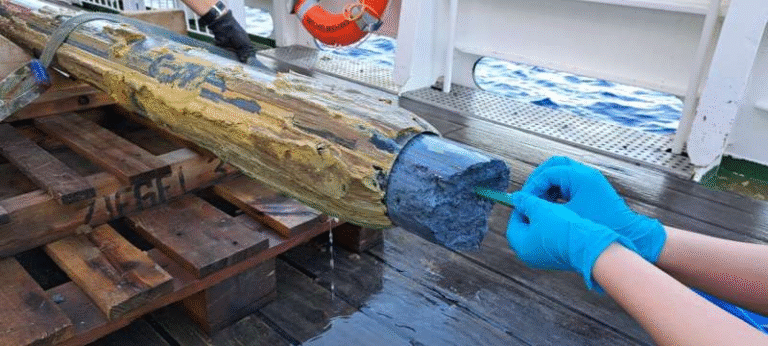

The investigation started with extensive field studies in China, where researchers examined thousands of fish collected over several years from multiple freshwater lakes. These lakes varied in their levels of pesticide contamination, allowing scientists to compare fish populations living in relatively clean environments with those exposed to agricultural runoff.

One striking pattern quickly emerged. Fish populations in contaminated lakes lacked older individuals, while fish from cleaner lakes included many older specimens. Importantly, this was not because contaminated lakes produced fewer fish. Instead, the data suggested that fish in polluted environments were dying earlier in life, before reaching old age.

This observation raised a crucial question: were these fish simply succumbing to toxic effects, or was something more subtle happening over time?

Measuring Aging at the Cellular Level

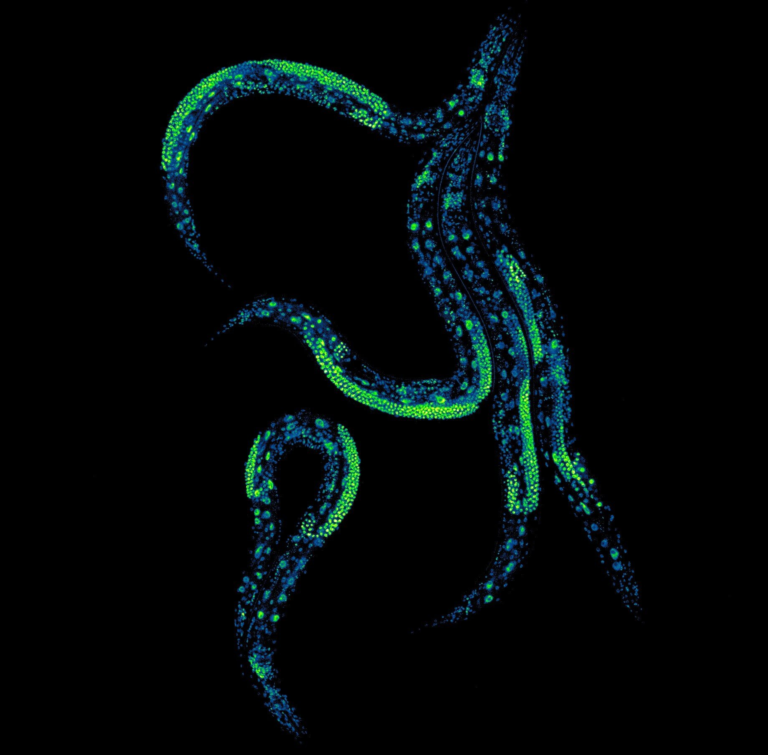

To answer that question, the research team analyzed two well-established biological markers of aging in the fish: telomere length and lipofuscin accumulation.

Telomeres are protective caps at the ends of chromosomes. They are often compared to the plastic tips on shoelaces because they prevent chromosomes from fraying during cell division. As organisms age, telomeres naturally shorten. Faster telomere shortening is widely recognized as a sign of accelerated biological aging.

Lipofuscin, on the other hand, is a buildup of cellular waste made up of damaged proteins, fats, and metals. It accumulates over time in long-lived cells and is often referred to as “aging pigment.”

The results were clear. Fish of the same chronological age from contaminated lakes showed shorter telomeres and higher lipofuscin levels than fish from cleaner lakes. In other words, even though they were the same age on paper, fish exposed to pesticides were biologically older.

Identifying the Culprit: Chlorpyrifos

Chemical analyses of fish tissues revealed something even more important. Among the various pollutants measured, chlorpyrifos was the only compound consistently linked to signs of accelerated aging.

This finding pointed strongly toward chlorpyrifos as the key driver behind the shortened lifespans. However, field studies alone cannot prove cause and effect. To confirm that chlorpyrifos was directly responsible, the researchers turned to controlled laboratory experiments.

Laboratory Experiments Confirm the Findings

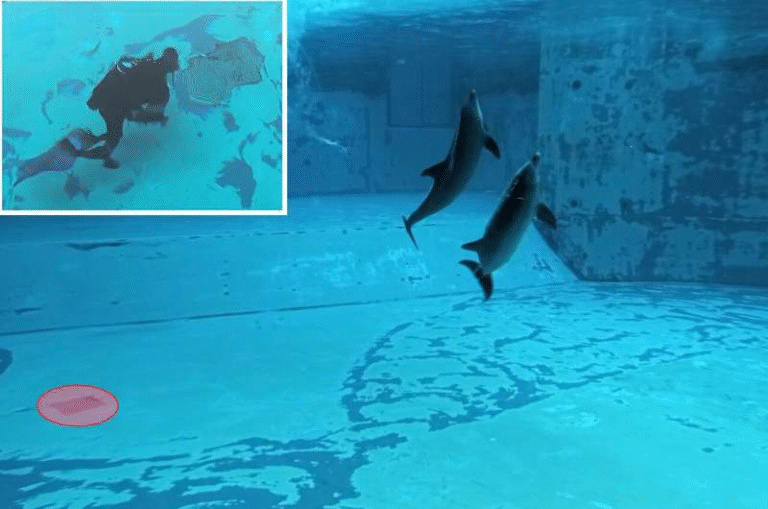

In the lab, researchers exposed fish to chronic low doses of chlorpyrifos that closely matched the concentrations found in the contaminated lakes. These doses were far below levels known to cause immediate poisoning.

Over time, the exposed fish showed progressive telomere shortening, increased lipofuscin accumulation, and reduced survival rates. The effect was especially strong in fish that originated from contaminated lakes, suggesting that previous exposure had already pushed them closer to physiological aging limits.

To rule out the possibility that brief but intense exposure events were responsible, the team conducted another experiment using short-term, high-dose exposure. These high doses caused rapid toxicity and death, as expected, but they did not produce the same aging markers seen with long-term low-dose exposure.

This distinction was crucial. It demonstrated that chronic accumulation, not short-term poisoning, was driving the accelerated aging process.

Why Losing Older Fish Matters

The absence of older fish in contaminated lakes is more than a demographic curiosity. Older individuals often play an outsized role in ecosystems. They tend to produce more offspring, contribute to genetic diversity, and help stabilize populations during environmental fluctuations.

When older fish disappear, entire aquatic ecosystems can become more vulnerable to collapse. This loss can ripple through food webs, affecting predators, prey species, and even water quality.

Implications Beyond Fish

One of the most concerning aspects of the study is that aging mechanisms such as telomere biology are highly conserved across vertebrates, including humans. While this research does not directly examine human health effects, it raises serious questions about how long-term, low-level pesticide exposure might affect other animals—and potentially people.

Chlorpyrifos has already been linked in previous studies to neurological and developmental harm. The new findings add accelerated aging to the list of potential risks, suggesting that damage may accumulate silently over time.

Regulatory Gaps and Global Use of Chlorpyrifos

The findings arrive amid ongoing debates about pesticide regulation. The European Union has largely banned chlorpyrifos, citing health and environmental concerns. However, the chemical is still used in China, parts of the United States, and many other countries.

Perhaps most troubling is that the aging effects observed in the study occurred at concentrations below current U.S. freshwater safety standards. This challenges the long-standing regulatory assumption that chemicals are safe as long as they do not cause immediate or obvious harm.

Standard safety assessments typically rely on short-term toxicity tests, which may completely miss slow, cumulative processes like accelerated aging.

Why This Study Matters

This research highlights a critical blind spot in how environmental risks are evaluated. Low-level chemical exposure may not cause visible damage right away, but it can quietly erode health over time by speeding up fundamental biological processes tied to aging and survival.

For environmental scientists, regulators, and public health experts, the study underscores the need for long-term testing frameworks that go beyond acute toxicity. For the rest of us, it serves as a reminder that “safe” does not always mean harmless—especially when exposure is constant and prolonged.

As future research expands to other species and chemicals, the findings could reshape how pesticide safety is assessed worldwide.

Research paper: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.ady4727