Mapping How Humanity Shaped the Global Diversity of Medicinal Plants

A new study published in Current Biology takes a detailed look at how humans and medicinal plants have been intertwined across history, geography, and culture. Instead of relying solely on modern medicine, our ancestors explored the natural world for treatments, fragrances, intoxicants, and various non-nutritional uses. This research uncovers how deeply that relationship runs and why certain regions around the world ended up with significantly more medicinal plant species than others. The study includes every specific data point, comparison, and regional insight uncovered by the researchers, providing a clear picture of how human movement, experimentation, and cultural traditions shaped the global map of medicinal plant diversity.

What the Study Looked At

The research team analyzed more than 32,000 medicinal plant species out of a global database of over 357,000 vascular plant species, revealing that roughly 9% have some documented therapeutic or non-nutritional use. Only vascular plants were included because they make up the overwhelming majority of land plants; non-vascular groups like mosses, liverworts, and hornworts were excluded.

The team studied plant use across 369 regions worldwide. They compared medicinal plant diversity in each area with the region’s total vascular plant diversity. This helps determine whether a region has a higher-or-lower-than-expected number of medicinal species relative to its overall ecological richness.

One consistent pattern held true: plant diversity is lower at high latitudes and increases closer to the equator, and medicinal plant diversity followed the same gradient. Tropical regions, already known for dense species richness, also display the highest medicinal plant counts.

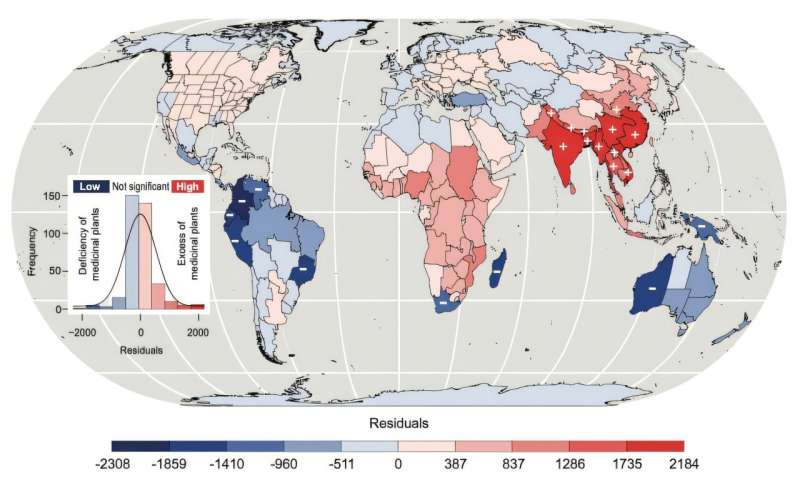

Identifying Hotspots of Medicinal Plant Use

While global diversity patterns make sense from a climate perspective, the researchers uncovered several surprising outliers—regions that had more medicinal plants than expected, even after accounting for their floral richness. These include India, Nepal, Myanmar, and China.

These areas have exceptionally long histories of human presence and longstanding medicinal traditions such as Ayurveda and Traditional Chinese Medicine. The researchers concluded that centuries or millennia of cultural experimentation contributed to this concentration of medicinal knowledge. Humans in these regions had extended periods to explore the natural environment, document remedies, and pass knowledge through generations.

The study suggests that time—not just biodiversity—allowed local populations to refine and expand their understanding of useful plants. The longer humans lived in a place, the more opportunities they had to identify effective treatments, meaning some modern medicinal richness may be the direct result of deep cultural continuity.

The Unexpected Cold Spots

Just as some regions exceeded expectations, others unexpectedly fell short. These cold spots include:

- The Andes

- The Cape Provinces of southern Africa

- Madagascar

- Western Australia

- New Guinea

These regions are globally recognized as megadiverse botanical areas. They contain many unique species and a rich evolutionary history, yet they have fewer documented medicinal plants than expected.

The authors note that this does not necessarily mean traditional medicinal use was absent. Instead, the lower counts may reflect:

- Incomplete ethnobotanical documentation

- Knowledge lost or erased by colonial disruptions

- Insufficient integration of local traditions into global datasets

The researchers highlight that many of these cold-spot regions still possess substantial unrecorded knowledge held by Indigenous or local communities. This points to a broader challenge in ethnobotany: scientific records often fail to capture the full range of human-plant relationships, especially in areas impacted by historical upheaval.

Human Settlement as a Key Predictor

One of the most important findings of the study is that the time of settlement by modern humans is the second-strongest predictor of medicinal plant diversity in a region. This factor has not been heavily examined in past research.

The comparison revealed clear distinctions:

- Sub-Saharan Africa, home to the earliest modern human populations, shows higher-than-expected medicinal plant usage.

- South America, settled relatively recently (between 25,000 and 15,000 years ago), has fewer medicinal plant species in use, even at similar latitudes.

This supports the idea that medicinal knowledge grows cumulatively. The more generations that interact with an environment, the more plant uses they discover, test, refine, and preserve.

Medicinal Plants Throughout Human History

The study also highlights how deeply plant-based medicine is embedded in human civilization. Examples include:

- Quinine, derived from fever bark (Cinchona lancifolia) and used to treat malaria

- Digitoxin compounds from foxglove (Digitalis purpurea), still used in heart medications

- Vincristine and vinblastine from the Madagascar periwinkle (Catharanthus roseus), essential chemotherapy drugs

- Paclitaxel (Taxol) from the Pacific yew (Taxus brevifolia), another major anticancer treatment

Evidence suggests these practices go back even further than written history. Certain primates use plants for wound care or digestive issues. Archaeologists discovered traces of medicinal plants like yarrow and chamomile in the dental plaque of ancient hominins.

The earliest written record of plant medicine appears on a 5,000-year-old Sumerian clay tablet listing more than 250 plant-based recipes. Ancient texts across cultures—including the Bible, the Talmud, the Iliad, and the Odyssey—reference medicinal plants. Early Greek physicians provided detailed lists of remedies, showing how ubiquitous plant-based healing was across civilizations.

The Threat to Biodiversity and Knowledge

Today, this entire heritage faces serious threats. The rapid loss of plant biodiversity worldwide means that species with potential medicinal value may disappear before scientists even study them. At the same time, traditional medicinal knowledge in many communities is fading as younger generations shift toward urban lifestyles or globalized health systems.

The researchers emphasize that conservation efforts must protect both biodiversity and cultural knowledge. Losing either one poses a risk to future scientific discoveries, including the possibility of finding new lifesaving drugs. Regions with long medicinal traditions—and even those where knowledge may have been disrupted—need focused attention to preserve their plant resources and revive or record their healing practices.

Additional Background: Why Medicinal Plants Matter Now

Medicinal plants remain essential even in the modern pharmaceutical world. An estimated 25% of prescription drugs contain ingredients derived from plants. Natural compounds often serve as templates for synthetic drugs because they are products of millions of years of biological refinement.

Ethnobotany, the field studying how humans use plants, continues to reveal leads for new medical research. Many breakthroughs in cancer treatment, pain management, and infectious disease control started as observations of how Indigenous or local groups used specific plants.

Understanding global patterns of medicinal plant diversity helps researchers identify which regions may contain promising species or overlooked traditions. It also creates a roadmap for conservation priorities.

Research Reference

The human fingerprint of medicinal plant species diversity (Current Biology, 2025)

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2025.09.050