Marine Predators Struggle with Uneven Nutrition as Prey Quality Varies Widely Across the Ocean

Scientists at the University of California, San Diego (UC San Diego) have uncovered something that changes how we think about life in the ocean: not all prey are created equal. Even within the same species, two fish of the same size can differ dramatically in their nutritional value, and this discovery could have major implications for marine ecosystems, predator survival, and fisheries management.

The research, published in the Journal of Animal Ecology in 2025, was led by Dr. Stephanie Nehasil, a former UC San Diego doctoral student, alongside Professor Carolyn Kurle and collaborators from the Southwest Fisheries Science Center (NOAA) and UC Santa Cruz. Their work started after a mass starvation event hit marine animals along the California coast during a 2014–2016 marine heat wave. That event, part of the California Current Ecosystem (CCE), disrupted food availability for sea lions, seabirds, and fish, leaving scientists wondering whether the problem was not just about how much food was available—but how nutritious that food really was.

How the Study Began

The California Current Ecosystem is one of the most productive ocean regions in the world, stretching for thousands of miles along the West Coast of North America. It supports everything from plankton to large marine mammals. But in 2014, a massive North Pacific heat wave—nicknamed “The Blob”—reduced the normal upwelling of cold, nutrient-rich water from the deep ocean. This lack of nutrients weakened the entire food web, beginning with microscopic zooplankton, and the effects rippled upward.

Marine mammals such as California sea lions were among the hardest hit. Many sea lion mothers were found emaciated and unable to feed their pups, leading researchers to ask a deeper question: was the issue only about prey quantity, or had prey quality itself dropped?

Digging into Prey Quality

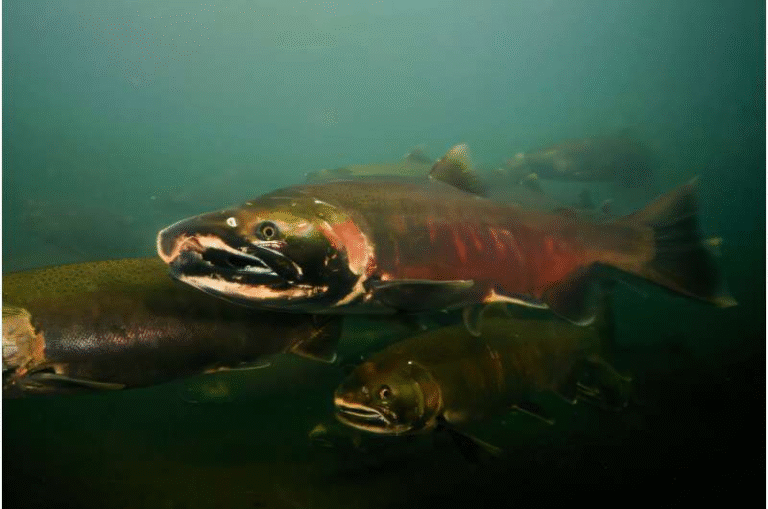

To find answers, Nehasil and her team conducted a multi-year investigation into the energy value of common sea lion prey—namely northern anchovy, Pacific sardine, and market squid.

Using data from NOAA fish surveys, California Department of Fish and Wildlife samples, and even bait barges, the team measured how much energy different individuals of the same species provided. To do this, they used a bomb calorimeter, an instrument that burns a sample and measures the heat it gives off—revealing how much energy density it contains.

Surprisingly, even within one species, the team found enormous variation. Two anchovies or sardines of identical length and weight could offer completely different amounts of energy. In other words, a predator could eat two fish of the same size but get twice the nutrition from one compared to the other.

What This Means for Predators

This finding has serious implications for marine predators like sea lions, seabirds, and larger fish that rely on consistent food energy to survive. The researchers discovered that if a predator feeds on lower-quality prey, it might need to double its intake to meet its daily energy needs.

In extreme cases, the energy variation was so large that a predator would need to consume tens of thousands of low-quality fish each day to survive—something biologically impossible. This suggests that even if prey numbers appear stable, predators can still starve if the energy content of their food declines.

The researchers incorporated these findings into bioenergetic models—tools that predict how much food predators need to sustain themselves. Traditionally, these models assumed that all prey of the same species and size were equally valuable. Now, with this new data, scientists can refine those models to more accurately reflect how ecosystems work.

Why Prey Quality Differs

The study found that environmental conditions, season, region, prey size, and maturity all influence a prey animal’s energy content. For example:

- In nutrient-rich areas where plankton thrive, prey tend to be fattier and more energy-dense.

- In warmer, less productive waters, prey are often leaner and provide less nutritional value.

- Younger fish tend to use their energy for growth, while older ones use more for reproduction, leading to different energy levels even within the same species.

This variation means that environmental shifts—like marine heat waves or nutrient shortages—can quickly cascade up the food chain, changing how much nourishment predators actually get.

Understanding the Bigger Picture

The results of this research highlight the importance of looking beyond biomass when studying ecosystems. Managers and conservationists often track the number or weight of fish available, assuming that more fish equals more food for predators. But if those fish are low in energy, abundance alone can be misleading.

This is particularly critical in the era of climate change, which is altering ocean conditions faster than many species can adapt. Warming waters, shifting currents, and declining nutrient upwelling can all lower prey quality. When that happens, predators may appear to have plenty to eat—but still face energy starvation.

For scientists and fisheries managers, this study provides a more precise understanding of how marine ecosystems function. Incorporating prey quality into existing food web and population models could lead to better conservation strategies for marine mammals and commercially important fish species.

Lessons from the California Sea Lion

California sea lions are often used as indicator species—animals whose health reflects the state of their environment. When they struggle, it usually signals deeper problems in the ecosystem.

During the 2014–2016 starvation event, thousands of sea lions washed ashore malnourished, and pup survival plummeted. The new research suggests that even if fish were available, their nutritional decline made it nearly impossible for mother sea lions to meet both their own needs and those of their young.

Understanding this helps explain why some recovery efforts based only on prey quantity failed to prevent sea lion starvation. It’s not enough to ensure there’s “enough fish” — those fish must also have sufficient energy density to sustain predators.

Beyond Sea Lions – Why It Matters Globally

While the study focused on the California coast, the concept applies globally. Many predators—from penguins in Antarctica to tuna in the Pacific—depend on prey whose quality fluctuates with changing ocean conditions.

If the same pattern of energy variability exists elsewhere, it could mean that predator populations worldwide are far more sensitive to prey nutrition than scientists once thought. Future studies may use this approach to reassess how environmental changes affect species survival and how we model global marine food webs.

The Future of Marine Food Web Research

The findings open a new chapter in marine ecology. Understanding that “a fish is not just a fish” could reshape how we manage fisheries, assess ecosystem health, and predict the effects of climate-driven ocean changes.

For example, fisheries management might begin measuring energy density alongside population size when evaluating stock health. Similarly, models that guide conservation policies for sea lions, seals, and seabirds could incorporate prey quality to predict future population trends more accurately.

The research also offers valuable baseline data for comparing future conditions. As oceans continue to warm, having detailed information about prey energy content will be essential for forecasting how predator-prey relationships evolve over time.

Final Thoughts

This study reminds us that ecosystems are far more complex than they appear. Two fish of the same size might look identical, but one could be packed with fat and energy while the other offers little sustenance. For a predator trying to survive, that difference can mean the line between thriving and starvation.

By revealing just how uneven the nutritional payoffs in the ocean can be, the UC San Diego team has given us a clearer window into how climate change and ecosystem shifts truly affect marine life. Their work highlights the need to think not just about how much food the ocean provides—but how good that food actually is.

Research Reference:

Nehasil, S. E., Zwolinski, J. P., Dorval, E., & Kurle, C. M. (2025). Intraspecific variation in prey quality affects the consumption rates of top predators. Journal of Animal Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.70155