Microbes May Hold the Key to Brain Evolution and How the Gut Shapes the Brain

A growing body of research has been pointing to an unexpected player in brain health and development: the gut microbiome. Now, a new study from Northwestern University adds a major piece to that puzzle by showing that gut microbes don’t just influence digestion or immunity — they can directly shape how the brain functions, and possibly how brains evolved in the first place.

The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), provides the first strong experimental evidence that differences in gut microbiomes across primate species can lead to meaningful differences in brain activity and gene expression. In simple terms, microbes may have helped fuel the evolution of large brains, including the human brain.

Why Brain Size Matters in Evolution

Humans stand out among primates for having the largest relative brain size compared to body mass. While this has long been linked to advanced cognition, social behavior, and problem-solving, it also creates a major biological challenge: brains are extremely energy-hungry organs.

Despite decades of research, scientists still don’t fully understand how mammals with larger brains evolved ways to meet the intense energy demands needed to grow and maintain them. Genetics and diet clearly play important roles, but they don’t tell the whole story.

This is where the gut microbiome enters the picture.

The Gut Microbiome as an Energy Partner

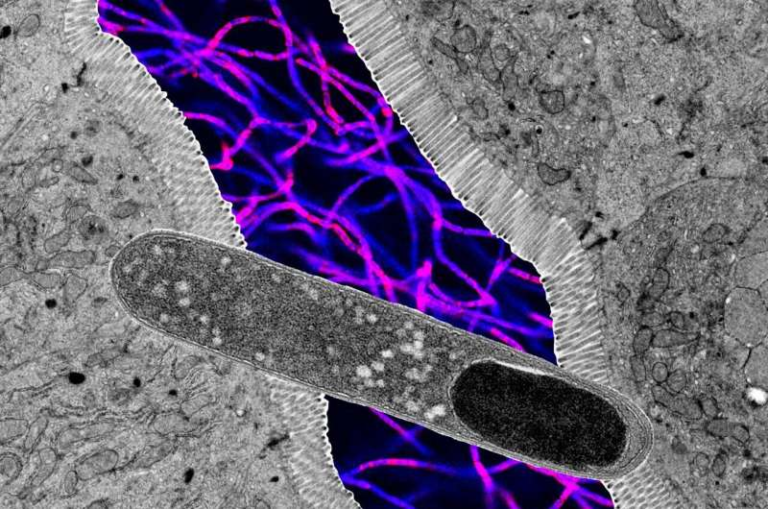

The gut microbiome is made up of trillions of bacteria, viruses, and other microorganisms that live in the digestive tract. These microbes help break down food, produce essential compounds, and regulate metabolism.

Earlier research from the same lab had already shown something intriguing: gut microbes from larger-brained primates generate more metabolic energy when transferred into laboratory mice. That finding suggested microbes might help support the high energy needs of bigger brains.

The new study took this idea one step further by asking a direct and critical question: Do these microbes also change how the brain itself works?

How the Experiment Was Designed

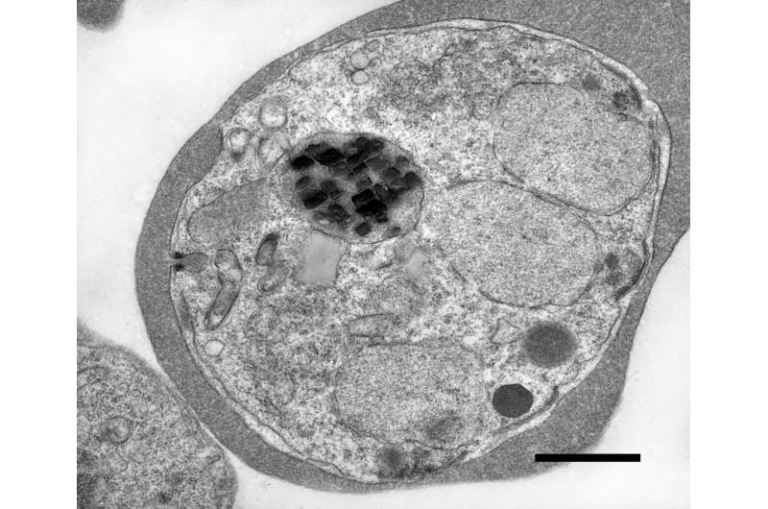

To answer this, researchers conducted a carefully controlled laboratory experiment using germ-free mice, which are mice raised without any gut microbes at all. This allowed scientists to precisely control which microbes the animals were exposed to.

The mice were given gut microbiomes from three different primate species:

- Humans, representing a large-brained primate

- Squirrel monkeys, another large-brained primate

- Macaques, a primate species with a relatively smaller brain

This setup allowed the researchers to compare the effects of microbes linked to brain size, rather than just genetic relatedness between species.

Clear Changes in Brain Function

Within eight weeks of altering the mice’s gut microbiomes, the researchers observed significant differences in how the animals’ brains were functioning.

Mice that received microbes from large-brained primates showed increased activity in genes related to:

- Energy production

- Neural metabolism

- Synaptic plasticity, which is the biological basis of learning and memory

In contrast, mice that received microbes from macaques showed lower expression of these same gene pathways.

This was a critical finding. It showed that gut microbes alone — without changing the animals’ DNA — could influence core brain processes tied to cognition and development.

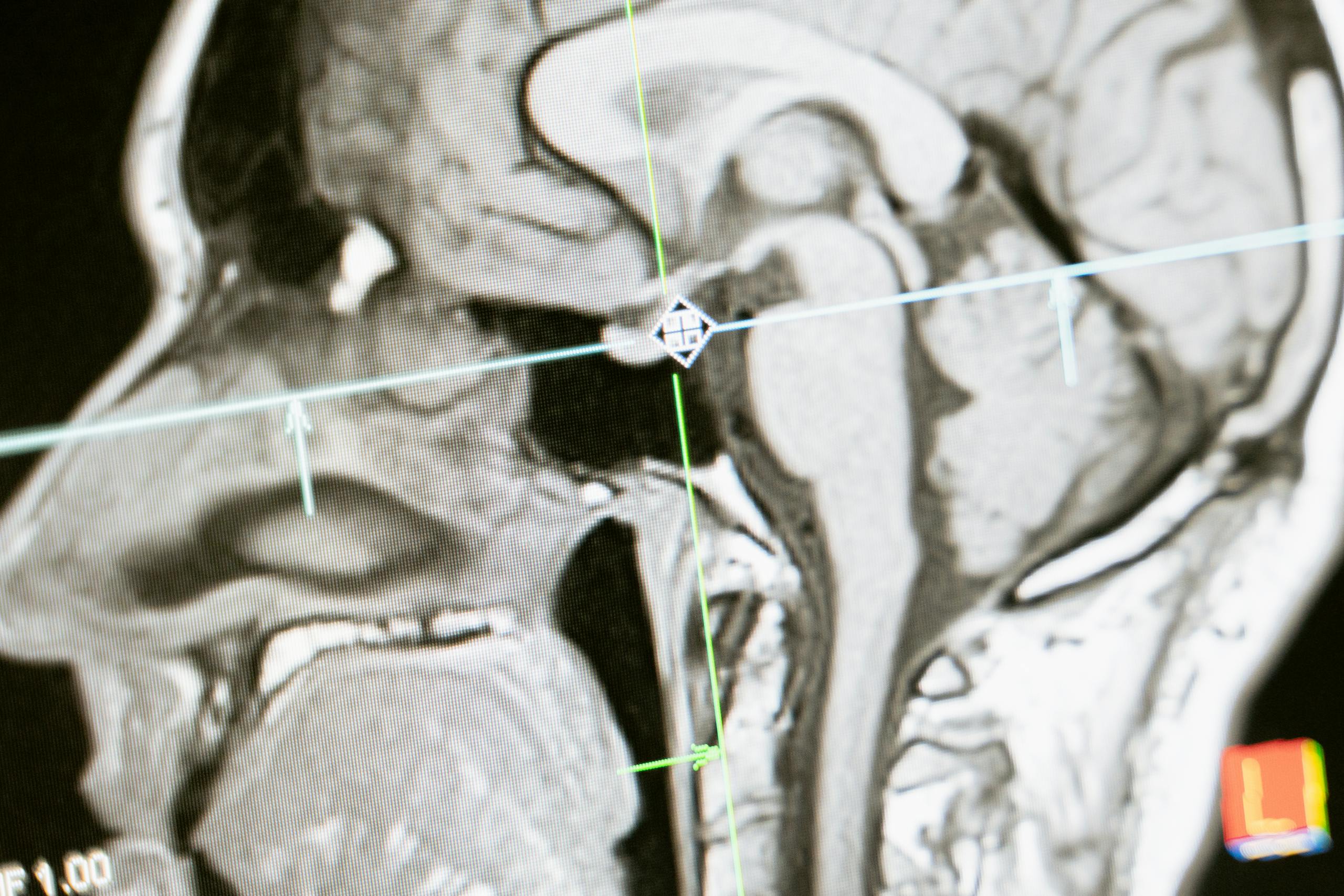

Mouse Brains That Resembled Primate Brains

One of the most surprising results came when researchers compared the mice’s brain data with existing data from actual primate brains.

The patterns of gene expression seen in the mice closely matched the patterns observed in the primates from which the microbes originated. In other words, the gut microbes from humans caused mouse brains to behave more like human brains at the molecular level, while macaque microbes pushed mouse brains toward macaque-like patterns.

This finding strongly suggests that microbes don’t just influence brain function in general — they may help shape species-specific brain traits.

Links to Neurodevelopmental Conditions

Another striking discovery emerged when researchers examined genes associated with neurological and psychiatric conditions.

Mice colonized with microbes from smaller-brained primates showed patterns of gene expression linked to conditions such as:

- ADHD

- Autism

- Schizophrenia

- Bipolar disorder

It’s important to be clear here: this does not mean that these microbes directly cause these disorders in humans. However, the findings add to growing evidence that the gut microbiome may play a causal role in shaping brain development, rather than simply being correlated with these conditions.

The study suggests that exposure to certain microbial communities during early development could influence how the brain is wired, potentially increasing or decreasing vulnerability to neurological differences.

What This Means for Brain Development

Taken together, the results point to a powerful idea: the gut microbiome may be actively involved in guiding brain development, especially during early life.

If the developing brain is exposed to microbial communities that are mismatched for its species or environment, brain function could be altered in lasting ways. This adds a new dimension to how scientists think about brain health, evolution, and developmental disorders.

An Evolutionary Perspective on the Gut–Brain Axis

From an evolutionary standpoint, these findings are especially fascinating. They suggest that microbes may have helped primates overcome the energetic barriers of evolving larger brains.

Instead of evolution relying solely on genetic mutations or dietary changes, gut microbes could have acted as metabolic partners, improving energy extraction and supporting enhanced brain function. Over time, this could have contributed to the dramatic brain expansion seen in humans.

Extra Context: How the Gut Talks to the Brain

The connection between the gut and the brain is often referred to as the gut–brain axis. This communication system involves multiple pathways, including:

- Neural signals via the vagus nerve

- Hormonal signaling

- Immune system interactions

- Microbial metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids

Gut microbes can influence neurotransmitter production, inflammation, and even stress responses. This study adds another layer by showing that microbes can also affect gene expression during brain development.

What Comes Next

The researchers emphasize that this is just the beginning. Future studies will aim to identify:

- Which specific microbes drive these effects

- How timing of microbial exposure influences brain outcomes

- Whether similar mechanisms operate in human development

The work opens new doors for understanding psychological disorders, evolutionary biology, and the possibility of microbiome-based interventions in the future.

Research Paper:

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2426232122