Microbial Engineering and Smart Design Offer New Hope for Tackling Global Plastic Waste

Researchers at the University of Waterloo are combining synthetic biology, microbial engineering, and engineering design in an ambitious effort to turn the world’s growing plastic waste problem into an opportunity for creating valuable new resources. This collaborative push focuses on breaking down plastics more efficiently, transforming plastic-derived molecules into usable products, and even redesigning certain plastics so they can be more easily recycled in the first place. The project brings together experts across chemical engineering, biology, and mathematics who believe that stepping out of their traditional research silos is essential for making real progress on one of the planet’s most persistent environmental challenges.

According to the United Nations Environment Program, an estimated 19 to 23 million tons of plastic leak into ecosystems every year. These materials can take centuries to degrade, and along the way they fragment into microplastics and nanoplastics that are now found everywhere—from ocean water and soil to the bodies of animals and humans. Recycling systems around the world struggle to keep up, and most plastics ultimately end up burned, buried, or lost in the environment. The Waterloo researchers argue that biological systems may offer a much more sustainable path forward by degrading plastics under mild conditions and turning them into helpful, rather than harmful, products.

How Synthetic Biology Could Change Plastic Recycling

One of the goals of the Waterloo team is to help build a circular plastics economy, where plastics at the end of their life are no longer treated as waste but instead reused as feedstocks for new products. Unlike traditional recycling methods—which typically rely on high heat, strong chemicals, and large amounts of energy—synthetic biology allows scientists to engineer organisms that can break down plastics gently and efficiently.

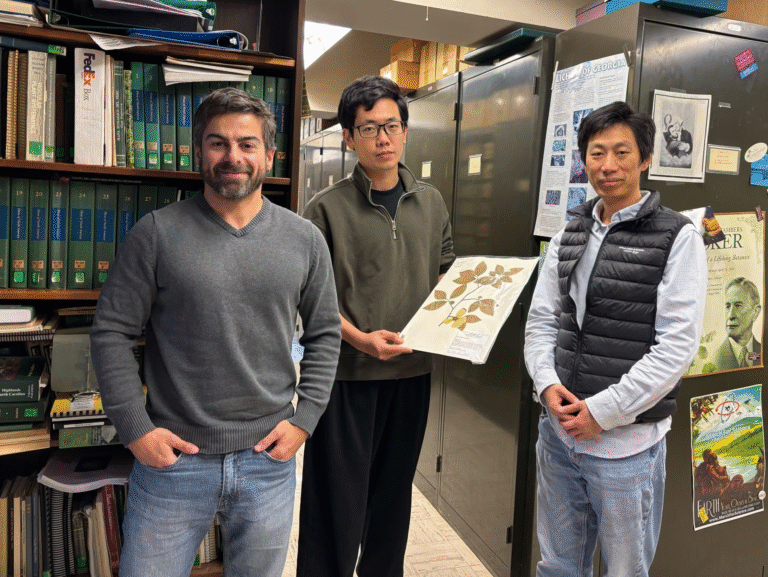

Researchers in this collaboration include Marc Aucoin, Christian Euler, Brian Ingalls, Yilan Liu, and Elisabeth Prince, each contributing expertise from their own fields. By working together, they’re evaluating a wide range of biological and biochemical strategies to degrade and upcycle plastics.

One major angle they are exploring is how engineered microbes can consume plastic-derived molecules and turn them into useful compounds. By modifying metabolic pathways, it becomes possible to encourage microbes to break plastics apart and convert the fragments into something valuable, such as chemical precursors, fuels, or biopolymers.

Exploring Mixotrophy to Transform Plastic Waste and CO₂

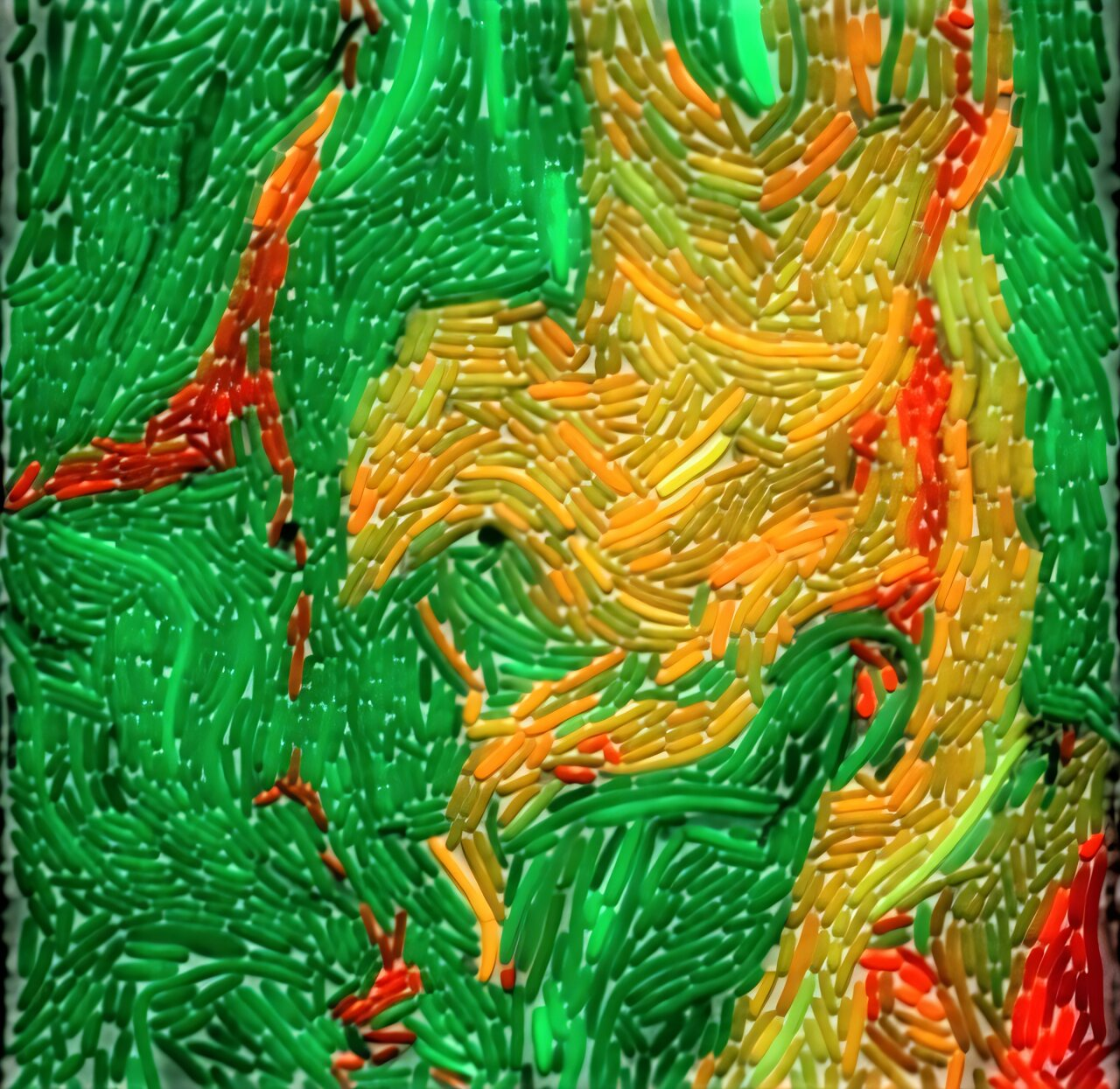

A recent study from Euler’s research group, published in PLOS Computational Biology, examined whether carbon sources derived from plastic waste could provide the energy needed for microbes to convert carbon dioxide (CO₂) into beneficial products. This metabolic strategy—called mixotrophy—involves microorganisms using multiple types of “food” at the same time. Most microbes typically favor one carbon source over another, but mixotrophic metabolism allows them to process both CO₂ and carbon from plastic waste.

Their analysis showed that several plastic-derived molecules can indeed support microbial CO₂ conversion. This means that a well-designed microbe could, in theory, address two environmental issues simultaneously: removing plastic waste and capturing CO₂. It’s a promising direction, because combining these processes inside a single organism could lead to more efficient and cost-effective recycling systems.

Their findings also reinforce the importance of degrading plastics early—such as inside wastewater treatment plants—before they break into microplastics that escape into natural ecosystems. Breaking down plastics at the source could significantly lower the amount of plastic pollution reaching waterways and soil.

Using Enzymes to Break Down PET Plastics

Another arm of the Waterloo initiative focuses on using enzymes to degrade polyethylene terephthalate (PET), one of the most widely used plastics in packaging, textiles, and consumer goods. PET is notoriously durable, but certain natural enzymes—like PET-degrading hydrolases—can break it down under the right conditions.

Aucoin, along with Ingalls and former Ph.D. researcher Aaron Yip, developed a process that uses such an enzyme to degrade PET. Their aim is to distribute either the enzyme itself or its genetic instructions among microbial communities commonly found in municipal wastewater systems. If these microbial populations can be engineered or encouraged to express the PET-degrading enzyme, wastewater facilities could become an early interception point for plastic pollution.

This approach would turn everyday bacteria into plastic-processing agents, capable of breaking down PET before it enters rivers, lakes, and oceans.

Engineering Microbes That Can Survive on Plastic Alone

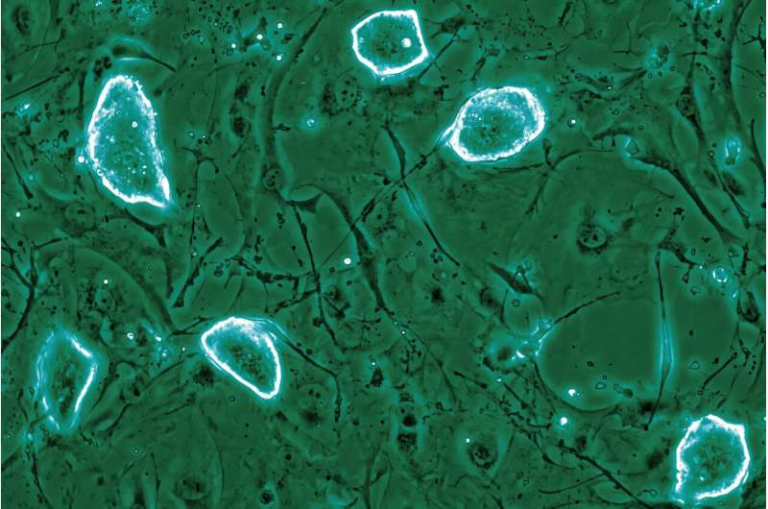

Meanwhile, chemical engineering professor Yilan Liu is taking a more radical approach: evolving microbes that can use plastic waste as their only food source. Her group works on designing synthetic symbiotic bacterial consortia, which are carefully balanced microbial communities that cooperate to degrade plastics more efficiently than individual strains could on their own.

Instead of relying on a single engineered microbe, her method uses groups of microbes with complementary metabolic roles. Some bacteria may specialize in breaking long plastic chains into smaller pieces, while others convert those fragments into new chemical building blocks. This cooperative strategy mirrors natural microbial ecosystems, which often achieve complex tasks through multiple interacting species.

If successful, these consortia could become highly efficient plastic-processing systems capable of transforming large amounts of waste.

Redesigning Plastics to Make Recycling Easier

The Waterloo collaboration doesn’t stop at breaking down the plastics we already have; it also looks at how future plastics should be designed. Elisabeth Prince, another researcher in the group, is developing ways to make traditionally non-recyclable materials—such as rubber tires, epoxy coatings, and thermoset polymers—recyclable without requiring manufacturers to overhaul their existing production systems.

She has created a technique that allows thermoset materials to be reprocessed simply by making minor changes to their chemical formulation. Since thermosets make up a huge category of durable goods but are rarely recyclable, this innovation could dramatically expand the types of materials that can participate in a circular economy.

Prince’s work shows that solving the plastic problem isn’t just about managing waste—it’s also about building smarter materials from the start.

Why Biological Solutions Matter in the Bigger Picture

Biological solutions are gaining attention worldwide because of the limitations of today’s recycling systems. Many plastics are not economically viable to recycle, and even when they are, the resulting materials are often lower in quality. Microbial and enzymatic methods offer several advantages:

- Lower energy requirements

- More targeted degradation

- Ability to upcycle plastics into higher-value materials

- Potential to capture CO₂ during the process

- Minimal toxic byproducts

As researchers develop more powerful enzymes and more efficient microbial consortia, biological recycling systems could become a key component of global waste management. This is especially important because plastic production is still increasing, and without new strategies, environmental pollution will continue to rise.

What Makes the Waterloo Initiative Stand Out

What’s notable about the University of Waterloo effort is not just the science, but the collaboration. Each member of the team contributes a different piece of the puzzle—enzyme engineering, microbial metabolism, polymer design, mathematical modeling, and systems engineering. This kind of interdisciplinary structure is becoming increasingly necessary for environmental research, where no single field has all the answers.

By combining their expertise, they are building a platform that can degrade plastics, upcycle waste streams, redesign materials, and propose systemic improvements to recycling infrastructure.

The ultimate goal is a true circular plastics economy, where materials continuously flow through productive loops instead of leaking into the environment.

Research Paper Reference

Harnessing synthetic biology to empower a circular plastics economy (Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 2025)

https://doi.org/10.1139/cjm-2025-0053