Mitochondria Move Toward the Cell Edge When Glucose Levels Rise and Scientists Are Finally Figuring Out Why

Mitochondria are often introduced as the “powerhouses of the cell,” but that label barely scratches the surface of what these tiny organelles actually do. New research now shows that mitochondria are not just busy producing energy — they are also highly mobile and capable of reorganizing themselves inside cells in response to changing conditions. A recent study published in the Biophysical Journal reveals that when pancreatic beta cells are exposed to high glucose levels, their mitochondria actively migrate toward the cell membrane, a movement that could have important implications for insulin secretion and metabolic health.

This finding adds an important new layer to how scientists understand the internal organization of cells, especially those involved in regulating blood sugar.

Mitochondria Are Not Fixed Structures Inside Cells

Unlike organs in the human body, organelles inside cells are not permanently anchored in place. They constantly move, interact, and reorganize, but scientists still know surprisingly little about when, where, and why these movements occur.

Previous research has shown that in neurons, mitochondria are strategically positioned in axons and dendrites, regions that are far from the cell’s center and require large amounts of energy. However, neurons have unusual shapes and extreme energy demands, so many researchers assumed this kind of targeted mitochondrial positioning was a special case.

Pancreatic beta cells, by contrast, are relatively compact and simple in shape, making them an unlikely candidate for complex mitochondrial choreography. That assumption turned out to be wrong.

What Happens to Mitochondria When Glucose Levels Rise

The researchers focused on pancreatic beta cells, the specialized cells responsible for producing and releasing insulin. These cells continuously sense glucose levels in the blood and adjust insulin secretion accordingly.

To observe mitochondrial behavior, the team labeled mitochondria in lab-grown beta cells using a fluorescent dye. The cells were then exposed to two glucose conditions:

- Low glucose: 2.5 millimolar

- High glucose: 25 millimolar

For comparison, normal human blood glucose levels typically range between 3.9 and 5.6 millimolar.

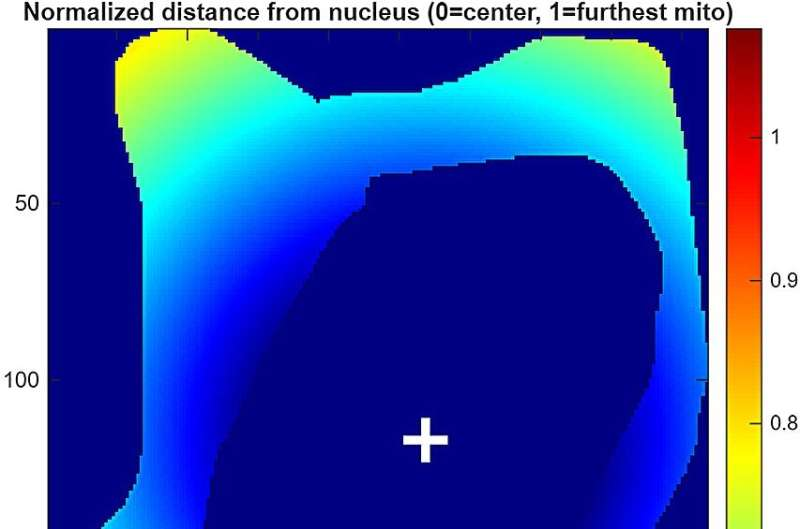

Under the microscope, a clear pattern emerged. In low-glucose conditions, mitochondria were distributed more evenly throughout the cell. But when glucose levels were high, mitochondria shifted toward the outer edge of the cell, clustering near the cell membrane.

This redistribution was not subtle. Quantitative analysis showed a significantly higher density of mitochondria at the cell periphery under high-glucose conditions.

Why This Movement Matters for Beta Cells

Mitochondria play a central role in how beta cells respond to glucose. When glucose enters these cells, mitochondria metabolize it to produce ATP, the cell’s main energy currency. Rising ATP levels then trigger a chain of events that leads to calcium influx and, ultimately, insulin release.

Because insulin secretion occurs at the cell membrane, the positioning of mitochondria closer to that membrane could potentially make the process faster, more efficient, or more precisely regulated. While the study does not yet prove a direct causal link between mitochondrial location and insulin output, it strongly suggests that where mitochondria sit inside the cell may be just as important as how much ATP they produce.

The Role of Microtubules in Mitochondrial Migration

To understand how mitochondria move toward the cell edge, the researchers examined the role of the cytoskeleton, specifically microtubules. Microtubules are structural protein filaments that act like internal highways, allowing cellular components to be transported from one location to another.

When the team chemically disrupted microtubules, mitochondrial movement toward the cell periphery was significantly reduced, even when glucose levels were high. This demonstrated that mitochondrial migration depends heavily on intact microtubule networks.

In other words, mitochondria are not drifting randomly — they are being actively transported.

cAMP Signaling Helps Drive the Process

The study also investigated the role of cAMP, a well-known signaling molecule involved in many cellular processes, including transport along microtubules.

When cAMP signaling was inhibited, mitochondria again failed to accumulate near the cell membrane, despite high glucose availability. This indicates that glucose likely triggers a signaling cascade involving cAMP, which then promotes mitochondrial attachment to microtubules and directed movement toward the cell edge.

This finding helps explain how cells translate a metabolic signal (high glucose) into a physical rearrangement of internal structures.

ATP Production Is Not the Driving Force

One of the more surprising findings of the study was what didn’t matter. When researchers inhibited mitochondrial ATP production, mitochondrial redistribution still occurred.

This means that the movement of mitochondria does not depend on their energy-producing activity. Instead, it is regulated by structural transport systems and signaling pathways, not by mitochondrial output itself.

This challenges the common assumption that mitochondria move simply to supply energy where it is needed most. In this case, their movement appears to be part of a broader regulatory mechanism tied to glucose sensing.

Insights From Computational Modeling

To tie everything together, the researchers developed a computational model that incorporated their experimental data. The model showed that when mitochondria bind to microtubules, their movement becomes faster and more directional, especially toward the cell periphery.

The model supports the idea that glucose acts as a trigger, enhancing mitochondrial–microtubule interactions and promoting edge-directed transport rather than random motion.

Why This Research Matters for Metabolic Health

Understanding how mitochondria behave in beta cells could have long-term implications for diseases like type 2 diabetes, where insulin secretion is impaired.

If mitochondrial positioning influences insulin release, then disruptions in this process could contribute to beta-cell dysfunction. Future research may explore whether defects in mitochondrial transport, microtubule structure, or cAMP signaling play a role in metabolic disease.

The researchers are now working on methods to directly visualize mitochondrial movement in real time and to test whether altering mitochondrial positioning changes insulin secretion levels.

A Broader Look at Organelle Dynamics

This study adds to a growing body of evidence that organelles are dynamic, responsive, and deeply integrated into cellular decision-making. Cells do not just rely on chemical signals; they also reorganize their internal architecture to adapt to changing conditions.

Mitochondria, in particular, are emerging as central hubs that connect metabolism, signaling, and cellular structure. Their ability to move in response to glucose highlights how finely tuned cellular systems really are.