More Trees, More Wildlife How Riparian Forest Cover Boosts Biodiversity in Agricultural Landscapes

A growing body of research has shown that trees do much more than simply shape the scenery of rural landscapes. A new study from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign adds strong evidence to this idea, revealing that increasing tree cover along streams and rivers in agricultural areas can significantly improve terrestrial biodiversity. In simple terms, more trees near farmland mean more wildlife, and the relationship is surprisingly measurable.

The research focuses on riparian buffers, which are strips of vegetation—often forested—located alongside waterways. Farmers and land managers have long used these buffers to reduce soil erosion, improve water quality, and manage runoff. What this study highlights is that these same buffers also act as vital refuges for land-based animals living in heavily farmed regions.

A Clear Link Between Tree Cover and Species Richness

The central finding of the study is striking. For every 10% increase in forest cover along riparian zones adjacent to agricultural fields, researchers detected one additional terrestrial species. This relationship held consistently across dozens of study locations, showing a direct and scalable benefit of tree cover.

Even more compelling, sites with complete forest cover along streams supported three times as many terrestrial vertebrate species as sites with little or no tree cover. These differences were not minor fluctuations but clear shifts in biodiversity levels that tracked closely with how much forest was present.

The research was led by Olivia Reves, who conducted the work as part of her master’s degree, alongside Eric Larson, an associate professor in the Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences. Their work took place across 47 sites in Central Illinois, a region dominated by intensive agriculture and ideal for studying how conservation practices influence wildlife.

How Environmental DNA Helped Reveal Hidden Wildlife

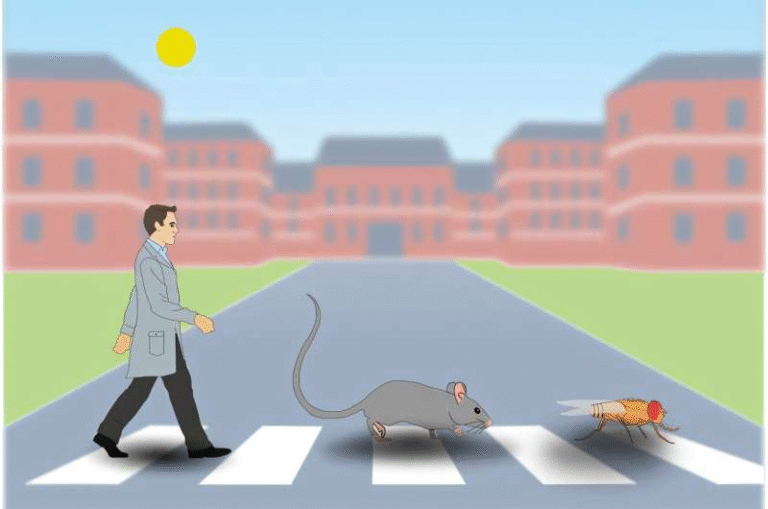

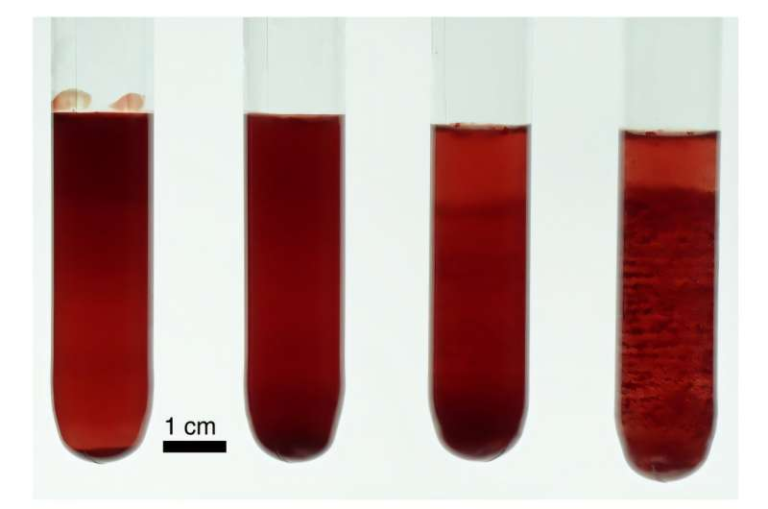

One of the most interesting aspects of this research is how the scientists measured biodiversity. Instead of relying solely on traditional wildlife surveys, they used a method called environmental DNA metabarcoding, often shortened to eDNA.

All animals shed tiny fragments of DNA into their surroundings through skin cells, hair, saliva, waste, and other biological material. In riparian environments, this DNA eventually makes its way into nearby water. By collecting water samples and analyzing the DNA fragments they contain, scientists can identify which species have recently used the surrounding landscape.

This approach allowed the researchers to detect animals that are difficult to observe directly. Common species like raccoons and common snapping turtles appeared frequently in the DNA samples, which was expected. More exciting were detections of species such as bobcats and big brown bats, animals that are elusive and rarely seen during standard surveys.

The key insight here is that streams act as natural collectors of DNA from across the landscape. Any animal that drinks from, crosses, or lives near the water leaves behind genetic traces that can be detected downstream. This makes eDNA a powerful tool for understanding biodiversity patterns, especially in complex agricultural environments.

Different Trees, Different Wildlife Communities

Beyond simply counting species, the researchers also examined how community composition changed with increasing forest cover. They found a clear gradient in the types of animals present.

At sites with low forest cover, the dominant species were those adapted to open or disturbed habitats. These included animals such as mice, ground squirrels, and killdeer, which are well suited to farmland and grassland environments.

In contrast, sites with high forest cover supported a completely different set of species. These included forest-dependent animals such as southern two-lined salamanders, North American river otters, and ruby-throated hummingbirds. The presence of these species indicates that riparian forests can function as genuine habitat, not just transitional zones, even within heavily farmed landscapes.

This turnover in species communities underscores that riparian buffers are not merely increasing numbers but are also supporting ecologically distinct wildlife assemblages that would otherwise struggle to persist in agricultural regions.

Why Riparian Buffers Matter Beyond Biodiversity

Riparian buffers have long been promoted for their environmental benefits, and this study adds another important dimension to their value. Forested buffers help stabilize stream banks, reduce nutrient runoff, and improve water quality by filtering sediments and pollutants before they enter waterways.

From an agricultural perspective, these buffers can also provide ecosystem services that directly benefit farmers. For example, insect-eating bats detected in the study help control agricultural pests, potentially reducing crop damage. Predatory species drawn to forested areas can also keep rodent populations in check.

Despite these advantages, not all landowners are enthusiastic about riparian buffers. Some view them as untidy or worry that they harbor pests. The findings from this study challenge those assumptions, showing that many of the species attracted to forested buffers actually contribute to healthier and more balanced ecosystems.

Environmental DNA as a Conservation Tool

The use of eDNA in this research highlights how rapidly biodiversity monitoring is evolving. Traditional surveys often require extensive field time, specialized expertise, and may still miss rare or nocturnal species. eDNA offers a non-invasive, efficient way to assess wildlife presence across large areas.

However, researchers are careful to note that eDNA does not replace all other methods. DNA can persist in the environment for varying lengths of time, and detection does not always indicate population size or long-term residency. Instead, eDNA works best as part of a broader monitoring toolkit, complementing visual surveys, trapping, and acoustic monitoring.

In agricultural landscapes where access and visibility can be limited, this method is especially valuable for uncovering hidden biodiversity benefits of conservation practices.

Implications for Agricultural Policy and Land Management

The results of this study have important implications for both voluntary conservation programs and regulatory approaches across the Midwest and beyond. By quantifying the biodiversity benefits of riparian forest cover, the research provides concrete evidence that can inform incentive programs, conservation planning, and land-use decisions.

Rather than framing riparian buffers solely as tools for water management, this work positions them as multi-benefit conservation features that support wildlife, improve ecosystem resilience, and enhance agricultural sustainability.

As pressures on land use continue to increase, studies like this help clarify how relatively small changes—such as increasing tree cover along streams—can yield significant ecological returns.

The Bigger Picture of Trees in Agricultural Landscapes

This research fits into a broader understanding that trees play a critical role in maintaining biodiversity outside of protected forests. In landscapes dominated by crops, forested riparian corridors can serve as movement pathways, refuges, and breeding habitats for a wide range of species.

They also help reconnect fragmented habitats, allowing wildlife to move more freely across the landscape. Over time, these connections can make agricultural regions more resilient to environmental change, including climate variability and extreme weather events.

By clearly linking tree cover to measurable biodiversity gains, this study reinforces the idea that conservation and agriculture do not have to be opposing forces.

Research Paper Reference

Environmental DNA quantifies the terrestrial biodiversity co-benefit of forested riparian buffers in agricultural landscapes

Journal of Applied Ecology (2025)

https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1365-2664.70206