mRNA Vaccine Technology Shows Promise in Reducing Snakebite-Related Muscle Damage

Snakebites remain one of the world’s most neglected health threats, causing around 140,000 deaths and 400,000 permanent disabilities each year. A major reason snakebites are so devastating is the severe local tissue destruction that occurs before victims can reach medical care. Now, researchers have found that the same mRNA technology used in COVID-19 vaccines could help protect muscle tissue from venom damage, offering a potential new tool in the fight against snakebite injuries.

A collaborative team from the University of Reading (UK) and the Technical University of Denmark has demonstrated that specially designed mRNA wrapped in lipid nanoparticles can teach muscle cells to produce antibodies that shield tissues from venom toxins. Their study focused on venom from the Bothrops asper snake, a species common in Central and South America and known for causing extensive muscle degeneration and long-term disability.

How the Experimental Treatment Works

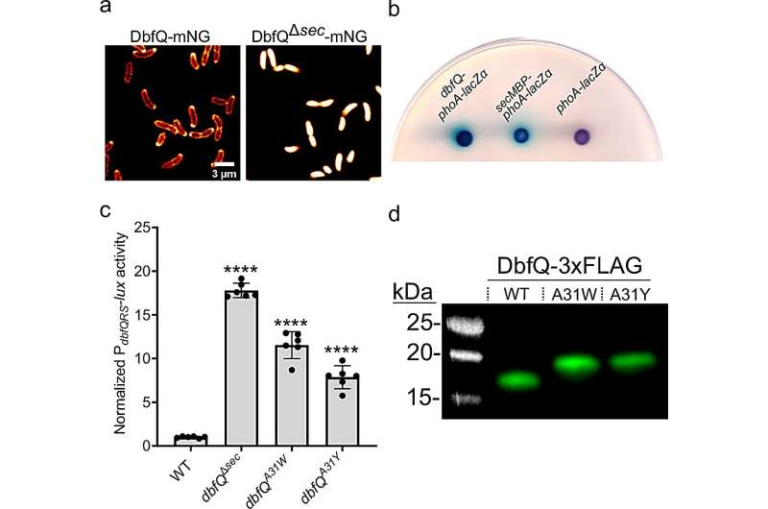

The researchers created mRNA molecules engineered to encode single-chain antibody fragments capable of neutralizing specific toxins found in the snake’s venom. These mRNA molecules were enclosed in tiny fat-based carriers, or lipid nanoparticles, similar to those used in COVID-19 vaccines. When injected into muscle, this formulation instructs the body’s own cells to produce protective antibodies directly at the site where venom damage typically occurs.

Protective antibody levels appeared in tissue within 12 to 24 hours of injection. In laboratory experiments using cultured human muscle cells, the treatment reduced muscle cell damage when exposed both to a single purified toxin and to whole venom.

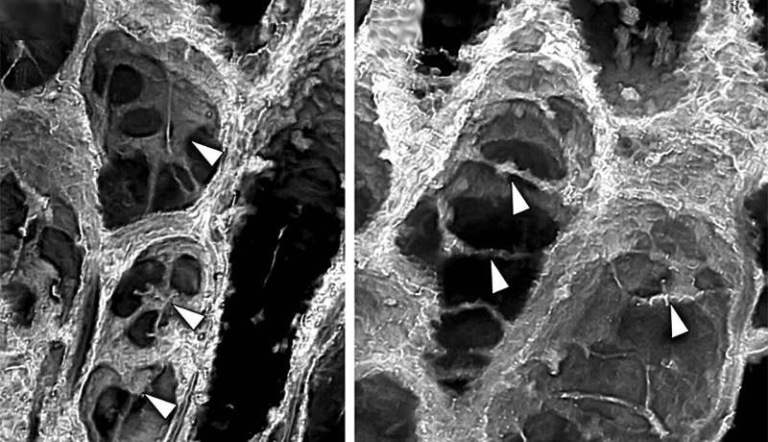

In live animal testing, mice received a single mRNA injection 48 hours before toxin exposure. Those treated mice showed significantly less muscle injury, much lower levels of biomarkers such as creatine kinase and lactate dehydrogenase, and better preservation of muscle structure compared to untreated animals. These biomarkers typically rise sharply in the bloodstream when muscle tissue is damaged, so their reduction is an important indicator of the treatment’s protective effect.

Notably, the treatment is intended to work alongside traditional antivenoms, not replace them. Antivenoms circulate through the bloodstream and neutralize systemic toxins well, but they struggle to address local tissue injury, especially in deep muscle around the bite site where antibodies don’t reach easily. The mRNA-based approach could help fill that gap by producing antibodies directly within the affected tissues.

Why Traditional Antivenoms Aren’t Enough

Snake venoms contain dozens of different molecules, many of which destroy tissues or disrupt important physiological functions. Antivenoms are highly effective at blocking toxins circulating in the bloodstream, but they do not always prevent localized muscle necrosis, which can occur within minutes of a bite.

Victims often arrive at medical facilities only after significant delay, allowing localized damage to advance beyond the reach of antivenom therapy. Even when delivered quickly, existing treatments struggle to stop venom components that embed themselves in muscle, causing long-term disability.

This is why researchers have long sought ways to neutralize toxins before they cause irreversible harm to muscle fibers. The mRNA-based method represents the first demonstration that it may be possible to program the body’s own cells to produce protective molecules in anticipation of venom exposure or potentially even after injury, once further development is completed.

Important Limitations and Challenges Ahead

Although the concept is promising, several hurdles remain before this technology can be used in real-world snakebite treatment.

First, the therapy currently targets only one toxin from the complex mixture present in Bothrops venom. Real-world snakebites involve multiple toxins acting simultaneously, so any usable treatment would need to protect against several venom components at once. Researchers plan to expand the mRNA approach to encode antibodies for additional toxins.

Second, the protective antibodies take several hours to develop after the mRNA is injected. For snakebite victims, minutes matter, and most people do not have access to preventive treatment. Scientists aim to shorten the time required for antibody production so that the therapy can be effective after a bite, not only before.

Third, mRNA formulations generally require cold storage, often at temperatures difficult to maintain in rural regions where snakebites are most common. Developing heat-stable formulations will be necessary for deploying this technology in remote areas.

The research teams both acknowledge these limitations but emphasize that the findings represent a major step forward. They plan to test whether the treatment can work when administered after venom exposure, and whether expanded mRNA cocktails can neutralize more venom components simultaneously.

Possible Applications Beyond Snakebites

While the current focus is on venom neutralization, the underlying approach has broader implications. Many diseases involve locally acting toxins, including certain bacterial infections. Because mRNA can be programmed to make many different antibody types, the platform could theoretically be adapted to:

- Block tissue-damaging toxins produced by bacteria during infection

- Deliver therapeutic antibodies directly to specific tissues

- Provide rapid, on-demand antibody production without the need for traditional protein manufacturing

Furthermore, mRNA technology is generally faster and more versatile to produce than conventional antibody drugs. This makes it attractive for responding to regional venom variations, emerging infectious diseases, or other toxin-related medical emergencies.

Understanding the Bothrops asper Snake

The Bothrops asper, commonly called the terciopelo or fer-de-lance, is responsible for a significant share of severe snakebite cases in Central and South America. Its venom contains powerful proteins that cause:

- Rapid muscle breakdown

- Severe swelling and bleeding

- Destruction of connective tissues

- Long-term disability, including permanent loss of mobility

Because of its wide distribution and aggressive defensive behavior, the species contributes heavily to the global snakebite burden. Effective treatments that prevent muscle destruction would dramatically improve recovery outcomes for thousands of victims each year.

Why mRNA Is a Strong Candidate for Future Snakebite Therapies

Several features make mRNA particularly suited for venom-related applications:

Speed of development – New mRNA constructs can be designed quickly to target specific toxins.

Flexibility – Multiple antibody targets can be encoded in a single formulation.

Localized expression – Injecting mRNA directly into muscle allows antibodies to be produced where they are needed most.

Reduced manufacturing complexity – Unlike protein-based antibodies, mRNA does not require large-scale cell culture production.

These advantages have already reshaped vaccine development and may soon transform how we approach venom injuries as well.

What This Research Means for the Future

While still in early stages, this study shows that mRNA technology could change how we think about snakebite treatment by focusing not only on survival but also on preserving muscle and reducing disability. Innovations like this could be especially transformative in rural regions where access to fast medical care is limited.

The research provides a compelling example of how scientific breakthroughs from one field — such as pandemic vaccine development — can spark new solutions in completely different areas of medicine. If further studies succeed, mRNA-based venom protection could eventually become a practical complement to traditional antivenom therapy.

Research Paper: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2025.10.017