New Breakthrough Shows How Human Stem Cells Can Finally Thrive Inside Animal Embryos

Scientists have taken a major step toward the long-imagined goal of growing human organs inside animals, and the new findings offer an unexpectedly clear explanation for why this has been so difficult until now. A research team at UT Southwestern Medical Center has identified a specific biological barrier that prevents human stem cells from surviving inside animal embryos—and, more importantly, they’ve shown how to switch that barrier off. This discovery, published in the journal Cell, outlines a straightforward yet powerful method that dramatically improves the ability of human cells to integrate into a developing mouse embryo. In the long run, this could open a practical path toward generating human-compatible organs in animals for medical transplantation.

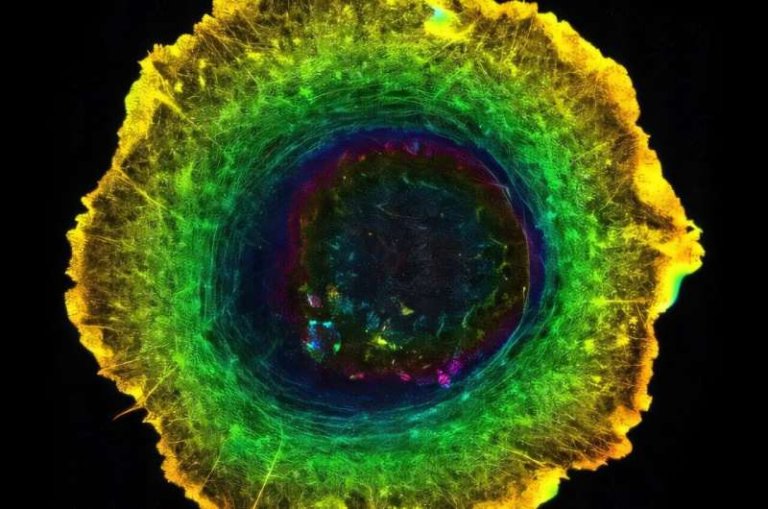

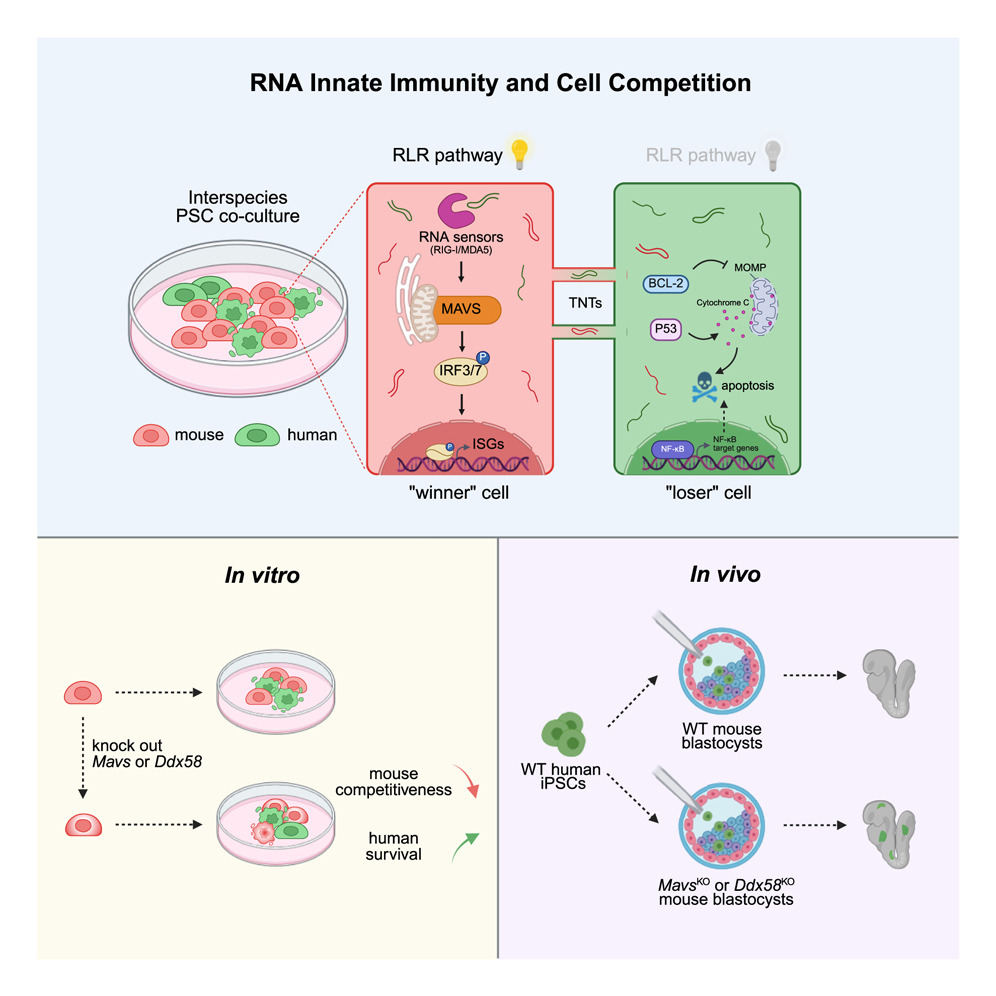

To understand why this matters, it helps to look at the central problem researchers have been facing. When scientists combine human pluripotent stem cells with mouse embryonic cells in a lab environment, something consistent happens: the mouse cells almost always outcompete the human cells. Human cells either fail to survive or contribute so minimally that the resulting embryo offers little useful insight. For years, scientists assumed this came down to differences in developmental timing or general cellular incompatibility. What the UT Southwestern team found is far more specific. Mouse cells, it turns out, activate a defensive mechanism whenever human RNA enters their environment. This defense belongs to what is known as RNA innate immunity, a system normally used to detect viral RNA and trigger antiviral responses.

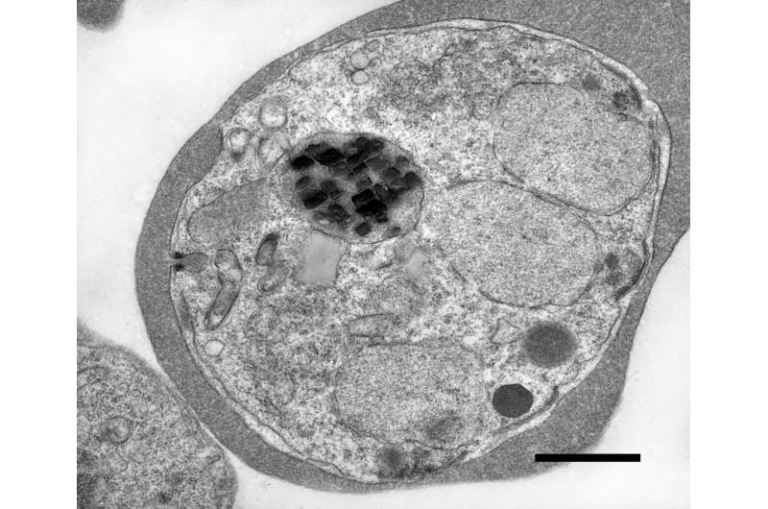

The mouse cells interpret human RNA as something foreign—something dangerous. They activate this immune response, and the cascade of effects weakens or eliminates nearby human cells. This built-in immune vigilance gives mouse cells a natural competitive edge, especially in early embryonic development where survival depends on subtle biochemical balances. Human cells don’t stand a chance when this immune machinery is active. This new research pinpoints the exact component responsible for kicking off this response: a gene called MAVS (short for mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein). MAVS is a core switch in RNA-based immunity. Without MAVS, the immune pathway does not activate in the same way.

So the researchers experimented with mouse embryos lacking this gene. When they disabled MAVS, the mouse cells no longer mounted a defensive reaction against human RNA. The result was dramatic—human stem cells survived at significantly higher levels and integrated more deeply into the developing chimeric embryo. This increased the overall chimerism, meaning a much larger portion of the embryo’s cells were of human origin. The human stem cells weren’t edited or enhanced in any way. They remained completely unmodified, which is a meaningful point for future transplantation safety. The improvement came entirely from making the mouse host more permissive.

This matters because many ethical and medical frameworks strongly prefer human cells that have not been genetically manipulated. If the host environment can be engineered to accept natural human cells, the path to real medical applications becomes far more realistic. Researchers emphasize that this work is still at the earliest embryonic stage in laboratory settings. No organs have been grown, and no functional chimera is anywhere near implantation or birth. But the discovery reveals a previously unknown barrier to interspecies stem cell integration—and provides a clear strategy to reduce it without altering the human donor cells.

While this specific finding focuses on mice, the implications extend to other species that researchers hope to use for organ generation, especially pigs. Pigs are considered ideal potential hosts because their organs are large enough and physiologically similar enough to human organs to be medically useful. However, human cells have consistently struggled to integrate within pig embryos as well. The same RNA-based immunity pathways exist in many mammals, so suppressing them in a controlled and ethical manner could improve chimerism in multiple host species.

To put the new discovery into context, it helps to understand the broader scientific challenges surrounding interspecies chimerism. Previous studies have shown that human cells often fail because of general cell competition, a natural process where stronger or more compatible cells eliminate weaker ones. In mixed-species environments, host animal cells typically have developmental advantages. Other research has shown that even basic cell adhesion—how cells stick to one another—can differ across species, making integration physically difficult. Developmental timing is another major challenge: human cells develop slowly, while mice develop rapidly, and this mismatch disrupts coordinated growth.

This newly identified immune barrier adds another piece to the puzzle. It shows that animal cells are not just passively outperforming human cells—they actively detect and suppress them through antiviral pathways. By turning off MAVS in host embryos, at least one of these active suppression mechanisms can be removed. The researchers also observed signs of horizontal RNA transfer, the sharing of RNA signals between cells, which triggers the immune detection. Preventing the host cells from reacting to this RNA is what allows human cells to finally establish themselves.

If this line of research continues to progress, its impact on medicine could be substantial. The shortage of transplantable human organs is severe, and thousands of people die each year waiting for compatible donors. The idea of growing personalized human organs inside animals has been a prominent but distant concept for decades. This new study does not complete that journey, but it clarifies a fundamental barrier and demonstrates a method to overcome it. Even though a fully formed organ grown in an animal host is still far off, the field has gained a clearer understanding of what must be solved to reach that point.

For readers who want to understand the science more broadly, RNA innate immunity is one of the oldest and most conserved biological defense mechanisms in the animal kingdom. Its purpose is to detect viral RNA, which often looks unfamiliar compared to the organism’s own RNA. When cells detect foreign RNA, proteins like MAVS trigger responses that include inflammation, cell signaling, and sometimes cell death. In normal biology, this helps protect organisms from infection. But in the context of mixing human and animal cells, the defense pathway becomes an obstacle.

Chimeric research has long walked a tight line of ethical questions, often related to concerns about animal welfare, human identity, and the boundaries between species. Current regulations restrict how far human-animal chimeras may develop, and no researcher is permitted to bring such embryos to full term. These ethical boundaries remain essential, and breakthroughs like this one support progress while staying firmly within regulated laboratory conditions.

Overall, the UT Southwestern team’s work highlights a surprisingly simple idea: sometimes the key to helping human cells thrive in a foreign environment is not to strengthen the human cells but to quiet the host. By adjusting the host embryo’s immune sensitivity, researchers opened a new path toward understanding and improving interspecies cell integration. Every detail discovered at this stage brings the scientific community one step closer to the long-term goal of creating reliable, safe, and scalable sources of human organs for transplantation.

Research Reference:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2025.10.039