New Chemical Method Makes It Easier to Select Desirable Traits in Crops

Crops around the world are under growing pressure to perform well in tougher environments. Drought, high soil salinity, and rising temperatures are no longer occasional challenges but persistent realities in many agricultural regions. While traditional plant breeding has helped farmers improve yield, resilience, and quality for centuries, it has one major limitation: it can only work with the genetic variation that already exists in a crop.

For many modern crops, that variation is surprisingly limited. Years of domestication and selective breeding have narrowed genetic diversity, making it harder to develop new varieties that can handle today’s rapidly changing conditions. A recent study published in PLOS Genetics introduces a promising workaround—a chemical-based method that allows researchers to generate large-scale genetic changes in plants without relying on radiation.

Why Genetic Diversity Is a Bottleneck in Crop Improvement

Selective breeding depends on naturally occurring differences between plants. Breeders cross plants with desirable traits and select the best offspring over multiple generations. This approach works well when a species has a wide genetic pool, but many crops have passed through domestication bottlenecks, where only a small number of plants contributed to modern varieties.

As a result, key traits such as salt tolerance, heat resistance, or improved water-use efficiency may simply not exist in current populations. This limitation has pushed scientists to explore mutation breeding, a strategy that deliberately introduces genetic changes and then screens plants for useful traits.

Mutation Breeding and the Limits of Radiation

One of the most common mutation-breeding tools involves radiation, which can create structural variants—large DNA changes such as deletions, duplications, or rearrangements that may affect multiple genes at once. These large-scale changes can produce dramatic and sometimes beneficial traits.

However, radiation-based approaches come with significant drawbacks. They require specialized facilities, involve strict regulations, and are not easily accessible to many research groups or breeding programs. These barriers restrict which crops can be studied and who can realistically use the method.

A Chemical Alternative to Radiation

The new method described in PLOS Genetics offers a simpler and more accessible alternative. Researchers led by Mary Gehring, a member of the Whitehead Institute and a professor of biology at MIT, developed a technique that uses etoposide, a drug commonly used in chemotherapy.

Etoposide interferes with topoisomerase II, an enzyme that plays a critical role in managing DNA structure during cell division. When this enzyme is disrupted, DNA strands can break. As plant cells attempt to repair this damage, errors in the repair process can occur, leading to large-scale genomic rearrangements.

What makes this approach especially useful is that these changes can become heritable. Seeds collected from treated plants carry the altered DNA and pass it on to the next generation.

How the Method Works in Practice

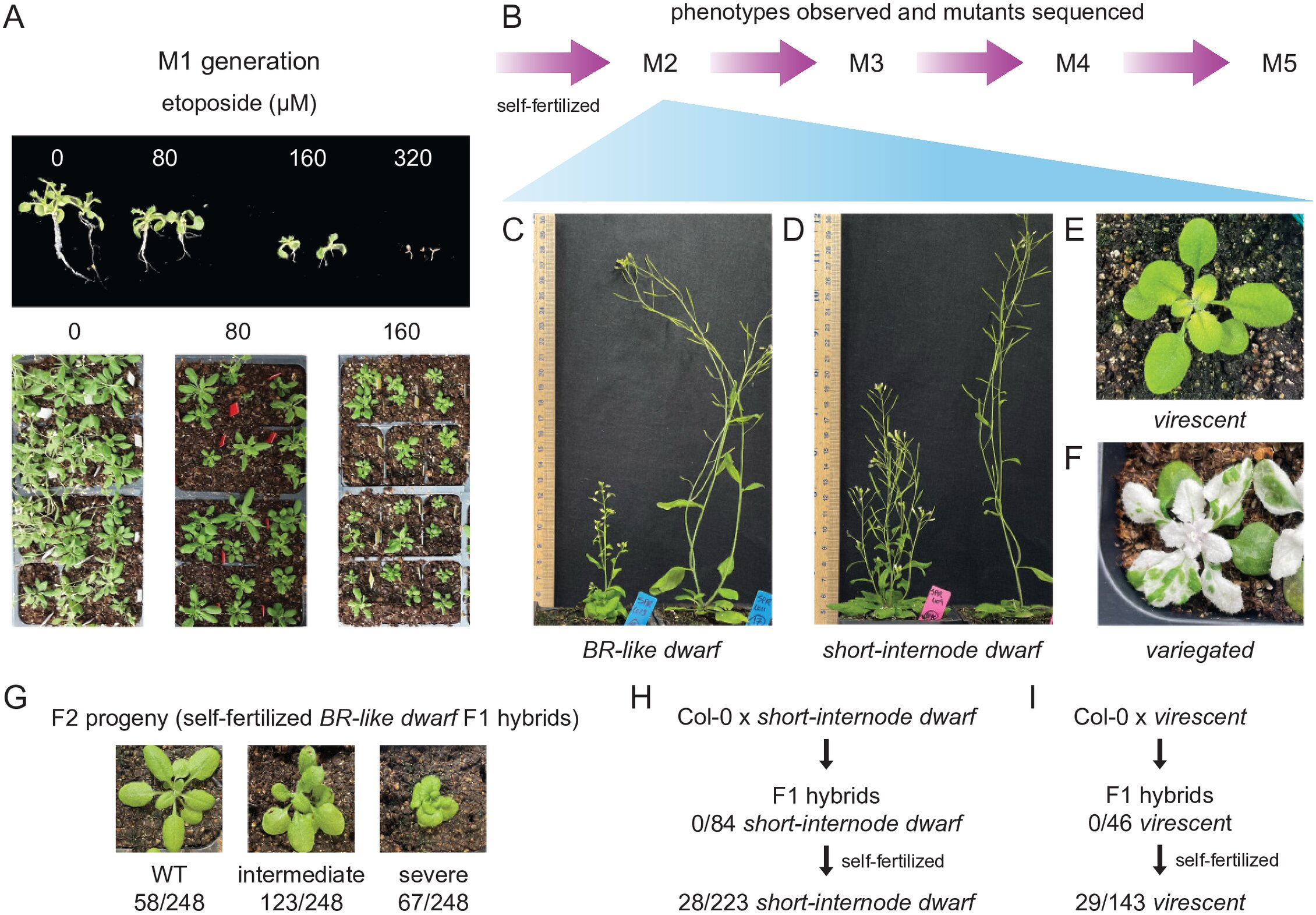

The process itself is relatively straightforward and relies on standard laboratory techniques. Seeds are germinated on growth media that contains etoposide during early development. After this initial treatment, the plants are transferred to soil and allowed to complete their life cycle normally.

This simplicity is a key advantage. Unlike radiation-based methods, there is no need for specialized irradiation facilities. The chemical treatment can be carried out in many plant biology labs using existing equipment.

Strong Results in Arabidopsis

The researchers first tested their approach using Arabidopsis thaliana, a widely studied model plant in genetics and plant biology. The results were striking. About two-thirds of treated plant lines showed visible differences in the very first generation.

These changes included variations in leaf shape, plant size, pigmentation, and fertility. Detailed genetic analyses revealed that these traits were linked to large structural changes in the genome, such as deletions and duplications of DNA segments.

In some cases, researchers were able to connect a specific physical trait to a specific genetic alteration. One dwarf plant with thick stems and unusual leaves had a major DNA change that disrupted a gene involved in leaf development. Another plant displayed green-and-white mottled leaves due to a deletion in the IMMUTANS gene—a gene known from radiation-induced mutants identified more than 60 years ago. This parallel strongly suggests that the chemical method can recreate the types of mutations traditionally achieved through radiation.

Expanding the Approach to Pigeon Pea

Beyond model plants, the team is applying this method to pigeon pea, a drought-tolerant legume that plays an important role in diets across parts of Asia and Africa. Pigeon pea is often classified as an orphan crop, meaning it receives relatively little research attention despite its importance for food security.

One major challenge with pigeon pea is its lack of genetic diversity, caused by a historical cultivation bottleneck. Many traits breeders would like to improve are simply not present in existing populations.

By using the etoposide-based method, researchers aim to artificially expand genetic diversity in pigeon pea. The team is currently screening treated plants for salt tolerance, a trait that strongly influences where crops can be grown and how well they perform in saline soils. Although pigeon pea takes longer to grow than Arabidopsis, the researchers have already reached the second generation and identified several promising lines.

How This Compares to Gene Editing Tools

Modern gene-editing technologies such as CRISPR allow scientists to make highly precise changes to DNA. However, CRISPR often depends on genetic transformation, a technically difficult step that many plant species do not tolerate well.

This limitation makes CRISPR challenging to use in numerous agricultural and horticultural crops. The chemical approach described here does not require genetic transformation and therefore offers a complementary option, especially for species that are hard to edit using current gene-editing tools.

Why Structural Variants Matter

Structural variants can have a much larger impact on plant traits than small genetic changes like single base mutations. By altering multiple genes or regulatory regions at once, they can produce dramatic phenotypic effects, both positive and negative.

Understanding how these large-scale genomic changes influence plant development is still an active area of research. To support this effort, Gehring’s lab plans to develop comprehensive collections of Arabidopsis mutants with well-characterized structural variants. These resources could help scientists better predict how genome structure shapes plant performance.

A Practical Step Forward for Crop Research

Rather than replacing existing tools, this chemical method expands the toolbox available to plant scientists and breeders. By lowering technical and regulatory barriers, it opens the door for more widespread experimentation, particularly in underutilized crops that are crucial for global food security.

As climate pressures intensify, approaches that increase genetic diversity quickly and efficiently could play a major role in developing crops that are more resilient, adaptable, and productive.

Research paper: https://journals.plos.org/plosgenetics/article?id=10.1371/journal.pgen.1011977