New Research Breaks Down the Complex World of Small-Scale Fisheries Into Five Clear Archetypes

Small-scale fisheries make up one of the most varied and essential food-producing sectors on the planet, yet they’ve long been difficult for researchers and policymakers to fully understand. A new Stanford-led study published in Nature Food attempts to bring clarity by analyzing 1,255 marine producers across 43 countries and sorting them into five archetypes based on factors like technology, distance traveled, market role, and what happens to the catch after it leaves the boat. The goal is straightforward: provide a clearer framework so governments, organizations, and consumers can make better decisions that support sustainable fishing, local economies, and global nutrition.

Small-scale fishers harvest around 40% of the world’s wild-caught fish, and their work may help feed up to a quarter of the global population. These are huge contributions, yet the sector has historically been lumped under vague labels like “artisanal” or “traditional,” which hide the realities of how differently small-scale fishers operate around the world. The new research shows just how broad the spectrum really is, spanning low-tech household food gathering to corporate-owned fleets with multiple paid crew members.

The project is part of a global effort called Illuminating Hidden Harvests, launched in 2017 and led by researchers at Stanford, Duke University, WorldFish, and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The initiative focuses on gathering stronger data about the benefits, challenges, and social importance of small-scale fisheries—data that is often missing from national records and global food policy discussions. The newly published analysis builds on this work by offering a more standardized way to classify what small-scale fisheries actually look like today.

Understanding Why Small-Scale Fisheries Are So Diverse

To understand the complexity, consider that small-scale fisheries target more than 2,500 species across environments ranging from coral reefs and shallow coasts to lakes, rivers, and offshore waters. Fishers use an extremely wide range of gear—nets, traps, hooks, hand tools—and boats that may or may not have motors, storage, or refrigeration. Some operators fish to feed only their household. Others supply local markets. Some export to global supply chains or sell to processing factories that turn fish into human food, animal feed, or fertilizer.

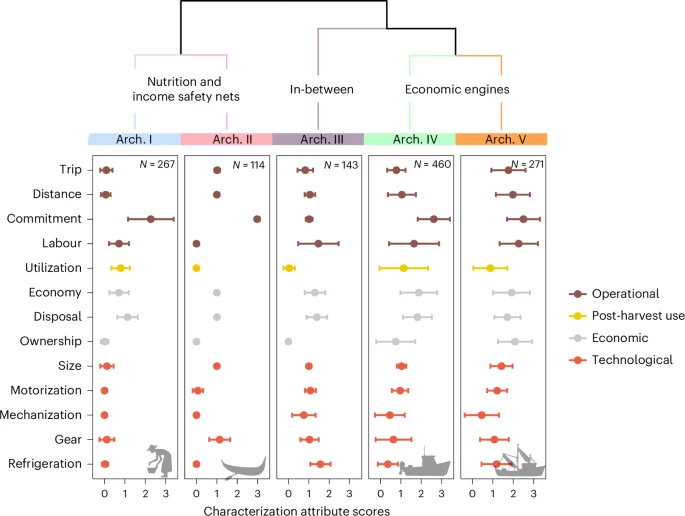

Because of all these differences, policymakers often struggle to create programs that work for everyone under the “small-scale” label. The authors describe this as a major source of policy paralysis and inaction, especially in cases where legal definitions of small-scale producers in farming, forestry, and fishing are inconsistent or overly broad. The new study responds to this challenge by grouping fisheries based on 13 measurable attributes, including motorization, trip distance, crew payment, storage capacity, and ultimate use of the catch.

The Five Archetypes Identified by Researchers

The study’s five categories show how significantly small-scale fisheries can differ.

1. Nutrition and Income Safety Nets

These fisheries represent the lowest-tech and lowest-capital segment. People may harvest clams or crabs by hand in shallow waters or use simple traps and nets from non-motorized boats. These operations rely heavily on family labor and usually supply subsistence needs or very local markets. They typically have no refrigeration, minimal government oversight, and no paid crew. According to the researchers, these kinds of fisheries exist in 19 countries and contribute around 4% of the global marine small-scale catch.

2. Seasonal Operators

A step up in technology, these fisheries use motorized boats and travel farther from shore but still mainly supply local consumption markets. Seasonal operators are common in countries such as China, India, Iran, and Turkey, and they sit between subsistence-focused groups and more commercial ones.

3. Economic Engines

These fisheries operate as major contributors to national economies. They often use motorized vessels equipped with storage and refrigeration and can spend days at sea targeting species like sardines and herring. Their catches move through broader domestic supply chains, and the operations often involve licenses, landing fees, and increased regulatory oversight. These fisheries provide important employment and financial stability in many coastal regions.

4. Middle-Range Hybrids

Some fisheries combine characteristics of both ends of the spectrum. They may have moderate technology, partial crew payment systems, or mixed market destinations. These occupy a broad gray space between purely subsistence activities and highly commercial ones.

5. Industrial-Like Small-Scale Fisheries

At the far end of the spectrum are operations that, although technically small-scale by certain national definitions, function in ways very similar to industrial fleets. These fisheries are corporate-owned, operate multiple boats, and employ several paid crew members. They have strong ties to both domestic and international markets. Countries with these types of fisheries include Indonesia, the Maldives, Argentina, and Peru. According to the study, they scored 29 or higher on the researchers’ measurement scale and account for roughly 2% of the global small-scale catch.

A Numerical Scale to Replace Vague Definitions

To show how these groups fall along a continuum, the researchers developed a 0–39 point scoring system. Low scores represent the most artisanal operations. High scores reflect commercialized structures, technology, and market integration. This method provides more nuance than simply categorizing vessels by size, which the authors note can be misleading. For example, in Argentina and Kenya, some small vessels behave like industrial fleets, while in Bangladesh, larger vessels managed cooperatively play a key role in local nutrition rather than global markets.

How Policymakers Could Use This New Framework

One major hope is that governments will use these categories to design more effective, targeted policies. For example:

- A country aiming to increase employment or economic output could help artisanal fisheries access better market channels, storage solutions, or financing.

- For more commercial fisheries, governments might focus on fuel-efficient vessel upgrades, real-time price data, or investment in infrastructure that supports larger supply chains.

The framework also supports the idea that a “one-size-fits-all” approach rarely works in the fishing sector. Different groups need different types of support, different regulations, and different development strategies.

What This Means for Consumers

The researchers say that this classification can help sharpen seafood guides, which many consumers use to choose species with lower environmental impact. With clearer data, guides can highlight which fisheries support local communities, which operate in more industrial ways, and where environmental considerations may differ based on fishing style rather than vessel size.

About the Illuminating Hidden Harvests Initiative

Since its launch in 2017, the IHH initiative has aimed to create a global picture of just how important small-scale fisheries are. The project involves partners across disciplines—social scientists, economists, ecologists, and community researchers—working together to measure the sector’s true value. By capturing diverse data on nutrition, livelihoods, gender roles, environmental impacts, and economic contributions, the project builds evidence that can guide both national policies and international development frameworks.

The new study adds a major piece to this effort by helping researchers and governments compare fisheries more clearly across countries and regions. It also illustrates the wide range of production strategies that fall under the small-scale label, showing how much nuance is lost when decision-makers rely only on vessel size or simplistic categories.

Why Clear Definitions Matter for the Future of Fisheries

Small-scale fisheries face rising threats from climate change, pollution, and overfishing. A more accurate classification system can make it easier to track which groups need the most support, what kinds of interventions work, and how different fisheries contribute to global food security.

Better definitions can also strengthen voluntary guidelines, including those associated with poverty reduction, nutritional improvement, and sustainable consumption goals.

The new framework gives researchers, governments, and organizations a way to evaluate fisheries with more precision and a clearer understanding of how they operate within larger food systems.

Research Paper:

Five Archetypes of Small-Scale Fisheries Reveal a Continuum of Production Strategies to Guide Governance and Policymaking – https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-025-01237-5