Opposing Forces Inside Human Cells Could Reveal New Paths for Treating Disease

Scientists at Penn State have uncovered a surprising internal conflict happening inside human cells—one that could significantly improve how we understand and eventually treat a wide range of diseases, including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and immune-related conditions. The discovery centers on how cells manage messenger RNA, or mRNA, the molecules responsible for carrying genetic instructions from DNA to build proteins.

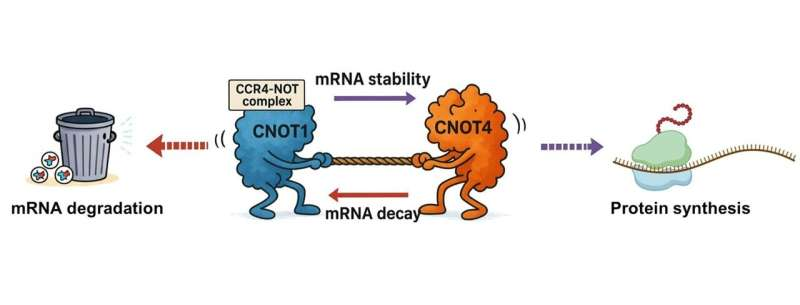

At the heart of this finding is a molecular machine called the CCR4-NOT complex, long known to play a major role in controlling the life cycle of mRNA. What researchers have now shown is that this complex is not as unified as once believed. Instead, it contains proteins that actively work against each other, creating a finely tuned balance that determines how long mRNA molecules survive inside the cell.

Understanding mRNA and Why It Matters

To understand why this discovery is important, it helps to first understand the role of mRNA. In simple terms, DNA stores genetic information, but it is mRNA that delivers the instructions needed to produce proteins. These proteins perform nearly every essential function in the body—from repairing tissue to fighting infections.

Once an mRNA molecule has delivered its instructions, it must be removed. If mRNA hangs around too long, it can lead to excess protein production. If it disappears too quickly, the cell may not produce enough protein. Either scenario can disrupt cellular balance and contribute to disease.

That clean-up job is largely handled by the CCR4-NOT complex, a group of proteins that helps regulate how and when mRNA is degraded.

A Molecular Tug-of-War Inside CCR4-NOT

For years, scientists assumed that all the proteins within CCR4-NOT worked together toward the same goal: breaking down mRNA. The new research challenges that assumption.

The Penn State team focused on two specific proteins within the complex: CNOT1 and CNOT4. CNOT1 serves as the central scaffold of the CCR4-NOT complex, holding the entire structure together. CNOT4, by contrast, has been less well understood and was thought to play a supporting role.

What the researchers discovered is that these two proteins actually have opposing effects on mRNA stability.

- CNOT1 encourages mRNA degradation, helping clear messages once they have done their job.

- CNOT4 slows down this degradation, acting as a stabilizing force that keeps mRNA around longer.

Rather than working in harmony, these proteins create a dynamic balance—more like a dimmer switch than an on/off button—allowing cells to fine-tune gene expression.

How the Discovery Was Made

To uncover these opposing roles, the research team used a powerful experimental tool known as the auxin-inducible degron (AID) system. This system allows scientists to rapidly and temporarily remove specific proteins from living human cells.

The experiments were carried out in a commonly used human colorectal cancer cell line called DLD-1. By tagging either CNOT1 or CNOT4 with the AID system, the researchers could trigger the cell to destroy the selected protein within about 60 minutes.

This precise control allowed the team to observe what happens to mRNA metabolism when each protein is removed individually.

What Happens When Each Protein Is Removed

The results were striking:

- When CNOT1 was depleted, the researchers observed widespread changes across thousands of RNA transcripts. mRNA molecules became more stable, and their degradation slowed significantly.

- When CNOT4 was depleted, the opposite occurred. mRNA degradation accelerated, even though the overall number of altered transcripts was relatively small.

This confirmed that CNOT1 and CNOT4 play distinct and opposing roles within the same molecular complex—something rarely seen in protein assemblies traditionally thought to function cooperatively.

Why This Balance Is So Important

Gene regulation depends on balance. Cells must constantly adjust which genes are active, how strongly they are expressed, and for how long. This process allows organisms to grow, adapt to environmental changes, and respond to stress.

The newly discovered opposition between CNOT1 and CNOT4 adds an important layer of control to this system. Instead of a simple degradation machine, CCR4-NOT appears to be a regulatory hub, capable of both accelerating and restraining mRNA decay depending on cellular needs.

When this balance fails, the consequences can be serious. Disrupted gene regulation has been linked to cancer progression, developmental disorders, metabolic diseases, and neurodegenerative conditions where protein levels must be tightly controlled.

CCR4-NOT: An Ancient but Still Mysterious Complex

The CCR4-NOT complex was first discovered in yeast in the early 1990s and is found in nearly all eukaryotic cells, including those of animals, plants, and fungi. While yeast studies have revealed much about its structure and function, human CCR4-NOT has remained less understood.

This study helps close that gap by showing that not all CCR4-NOT subunits behave the same way in human cells. Some subunits actively promote RNA decay, while others restrain it, adding flexibility to gene regulation.

What This Means for Disease Research and Treatment

Understanding how mRNA stability is regulated opens up several promising possibilities:

- Disease identification: Certain diseases may be associated with abnormal activity of CNOT1 or CNOT4, leading to characteristic mRNA decay patterns.

- Biomarker development: Changes in mRNA stability could serve as indicators for diagnosing or tracking disease progression.

- Therapeutic strategies: Future treatments could aim to adjust mRNA stability rather than completely turning genes on or off, offering more precise control.

Because mRNA-based therapies are already being explored in areas like cancer and vaccine development, insights into mRNA decay mechanisms are especially valuable.

The Power of the AID System

Beyond the biological findings, the study also highlights the usefulness of the auxin-inducible degron system. Being able to rapidly remove proteins without permanently altering the cell allows researchers to observe cause-and-effect relationships with remarkable clarity.

This approach opens the door to uncovering additional hidden roles of proteins that may have gone unnoticed using traditional methods.

Looking Ahead

The discovery that CCR4-NOT contains internal opposing forces changes how scientists think about molecular complexes involved in gene regulation. Rather than acting as simple machines, these complexes may function more like balanced control systems, constantly adjusting cellular behavior.

As researchers continue to explore how these opposing forces interact, they may uncover new ways to restore balance when gene regulation goes wrong—offering hope for more targeted and effective treatments in the future.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbc.2025.110862