Plant Hormone Technology Now Lets Scientists Control Protein Levels Throughout an Animal’s Entire Life

Scientists have achieved something that was long considered out of reach in biology: precise, lifelong control of protein levels inside a living animal, adjusted tissue by tissue, without harming normal growth or behavior. This breakthrough comes from researchers at the Center for Genomic Regulation (CRG) in Barcelona and the University of Cambridge, who have successfully adapted a plant hormone–based system to work in animals in a far more refined way than ever before.

The study, published in Nature Communications, demonstrates how proteins can now be dialed up or down with remarkable accuracy across different tissues of a whole organism, from birth to old age. This level of control opens entirely new doors for studying aging, disease, and how organs communicate with each other over time.

Why Protein Control Matters So Much in Biology

Proteins are the workhorses of life. They regulate metabolism, control cell division, transmit signals between cells, and help maintain the structure of tissues. While genes provide the instructions, proteins are what actually do the job.

For decades, scientists have relied on genetic tools that turn genes completely on or off. While powerful, these approaches come with major limitations. In real biological systems, proteins rarely act in an all-or-nothing way. Small changes in protein levels can produce subtle but important effects, especially in processes like aging, where gradual molecular shifts accumulate over time.

Until now, researchers lacked a reliable method to finely tune protein levels in specific tissues throughout an animal’s entire lifespan. That gap has made it difficult to answer fundamental questions such as how much of a protein is actually needed for health, or how changes in one tissue influence the rest of the body.

Borrowing a Trick From Plants

The new technique is based on a system that originally evolved in plants. Plants use a hormone called auxin to regulate growth and development. Auxin works by triggering the destruction of specific proteins when they are no longer needed.

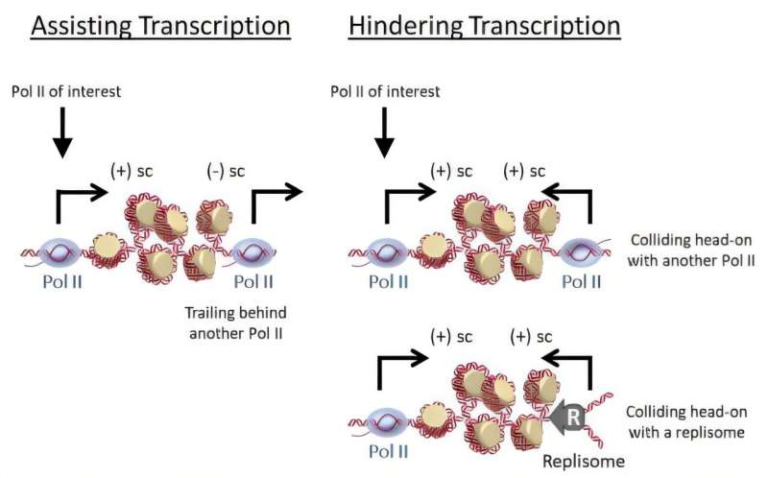

Years ago, scientists adapted this idea into a laboratory tool called the auxin-inducible degron system, commonly known as the AID system. In its basic form, the system works like this:

A target protein is tagged with a small molecular label known as a degron. Another protein, an enzyme called TIR1, recognizes this tag but only when auxin is present. Once auxin is added, TIR1 binds to the degron and marks the target protein for destruction by the cell’s natural recycling machinery. Remove auxin, and the protein begins to accumulate again.

This approach has been widely used in cells and some model organisms, but it has mostly functioned as a simple on/off switch. It also struggled to work consistently across different tissues and life stages.

The Dual-Channel AID System Explained

The researchers behind the new study wanted something more refined. Instead of completely eliminating a protein, they aimed to control how much of it remains, where it is controlled, and when that control occurs.

Their solution was a newly engineered dual-channel AID system. Rather than relying on a single version of TIR1 and a single auxin compound, they created two distinct TIR1 enzymes, each activated by a different auxin molecule. This allowed them to run two independent control systems at the same time.

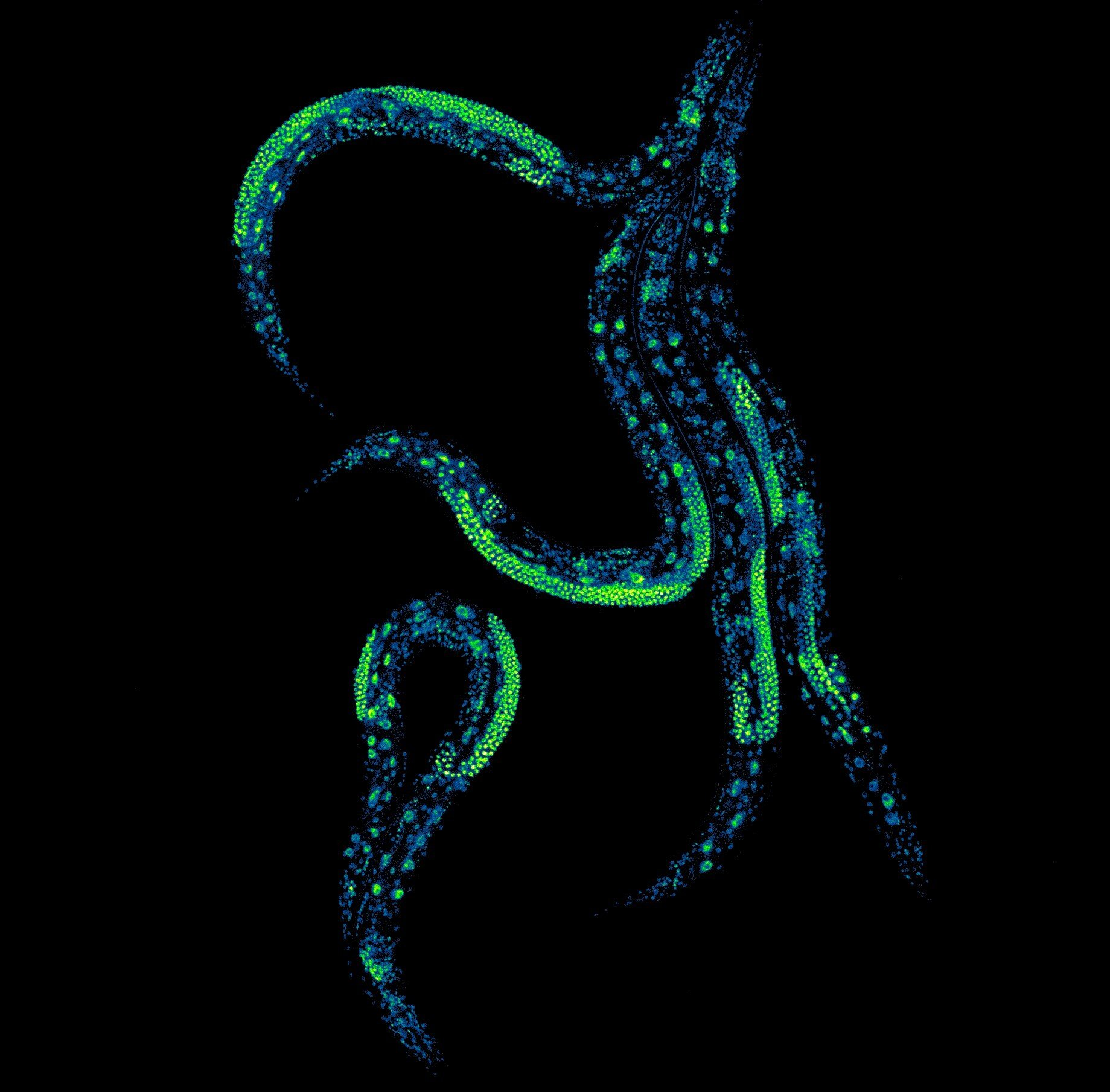

By genetically engineering animals so that each TIR1 enzyme is produced only in specific tissues, the scientists gained the ability to independently regulate the same protein in different organs, such as the intestine and neurons. They could also control two different proteins simultaneously within the same animal.

Crucially, this system does not simply flip proteins on or off. By adjusting the concentration of auxin in the animal’s food, researchers can fine-tune protein levels, much like adjusting the volume on a television.

Testing the System in Living Animals

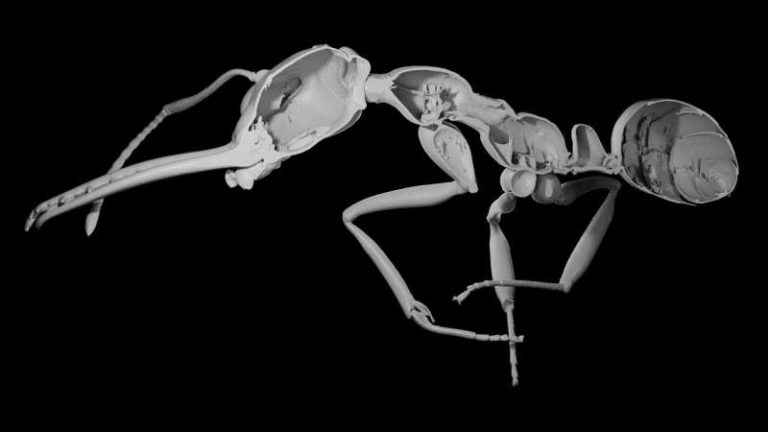

The experiments were carried out using Caenorhabditis elegans, a tiny nematode worm that is one of the most widely used model organisms in biology. Despite its simplicity, C. elegans shares many fundamental biological pathways with humans and has been central to aging research for decades.

The team tested their system across more than one hundred thousand worms, carefully evaluating different combinations of degron tags, TIR1 variants, and auxin compounds. This large-scale testing was necessary to ensure that the system worked reliably, did not interfere with normal development, and allowed consistent control throughout the animal’s life.

One major achievement was overcoming a known limitation of earlier AID systems: poor performance in reproductive tissues. Protein control in germline cells has historically been difficult due to unique biological processes that protect reproductive material. The researchers traced the source of the problem and adapted their system so that it now works across the entire body, including reproductive cells.

Why This Is a Big Deal for Aging Research

Aging is not driven by a single gene or protein. It emerges from complex interactions between tissues, organs, and molecular pathways over time. Some proteins may extend lifespan when reduced in one tissue but shorten it when reduced elsewhere. Traditional genetic methods often cannot separate these effects.

With this new system, scientists can now explore questions that were previously impossible to test. They can ask how partial reductions in a protein affect lifespan, how early-life changes differ from late-life changes, and how disturbances in one tissue ripple through the rest of the organism.

Because the system works while animals continue to eat, move, grow, and reproduce normally, it offers a realistic view of biology as it unfolds in living organisms, not just isolated cells.

Beyond Aging: Broader Scientific Impact

While aging research is a major focus, the implications extend much further. Precise protein control could help scientists better understand neurodegenerative diseases, metabolic disorders, developmental biology, and systemic diseases that involve multiple organs.

The dual-channel design also introduces a powerful way to study protein cooperation, allowing researchers to manipulate interacting proteins in different tissues at the same time. This could shed light on how biological networks maintain balance and what happens when that balance is disturbed.

Although the current study focuses on worms, the underlying principles could eventually inspire similar tools in other model organisms. Even if direct translation to humans is far off, the insights gained from such precise animal models can guide future biomedical research.

A New Level of Precision in Living Systems

What makes this work stand out is not just that proteins can be controlled, but that they can be controlled gradually, reversibly, and independently across tissues for an entire lifetime. That combination of precision, flexibility, and longevity has been missing from the biological toolkit.

By adapting a plant hormone system and pushing it far beyond its original design, the researchers have created a method that feels less like a blunt instrument and more like a finely tuned control panel for living organisms.

As biology moves toward understanding complex, system-wide processes rather than isolated components, tools like this dual-channel AID system are likely to play a central role.

Research paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-66347-x