Polar Bears Provide Millions of Kilograms of Food to Arctic Scavengers Every Year, New Study Reveals

A new scientific study has uncovered just how vital polar bears are to the broader Arctic ecosystem, not only as top predators but also as major food suppliers for other species. The research, published in the journal Oikos in 2025, shows that polar bears leave behind approximately 7.6 million kilograms of carrion—the remains of their prey—each year. This massive amount of leftover food sustains a variety of Arctic scavengers, from foxes and gulls to ravens and wolves.

A First-of-Its-Kind Quantification

The study was conducted by scientists from the University of Manitoba, the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, Environment and Climate Change Canada, and the University of Alberta. Lead author Holly Gamblin, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Manitoba, and her colleagues set out to measure just how much biomass polar bears contribute to the Arctic’s food web.

By combining data from field observations, prey mass estimates, and polar bear feeding habits, the team calculated that the remains from polar bear kills add up to millions of kilograms of food each year. Most of this comes from seals, particularly ringed seals and bearded seals, which polar bears hunt on the sea ice.

The researchers emphasized that this study is the first to quantify the scale at which polar bears serve as carrion providers for other animals. While previous work highlighted the polar bear’s role as an apex predator, this research demonstrates that their hunting behavior links marine and terrestrial ecosystems in an unexpected way.

How Polar Bears Transfer Ocean Energy to the Ice

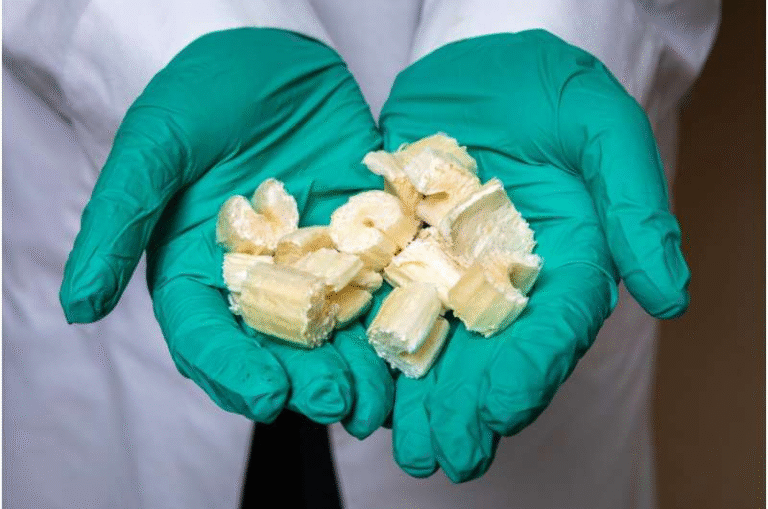

Polar bears are unique in their hunting strategy. They catch marine prey such as seals and then drag them out of the water onto sea ice to feed. This process inadvertently makes a large portion of the prey available to other animals. The bears often consume only part of the carcass—primarily the blubber and soft tissues—leaving behind bones, skin, and muscle that are still rich in nutrients.

This leftover material acts as an energy bridge between the ocean and the land. Because the carcasses remain on the sea ice or nearby shores, terrestrial and avian scavengers have access to marine-derived nutrients that they would otherwise never obtain.

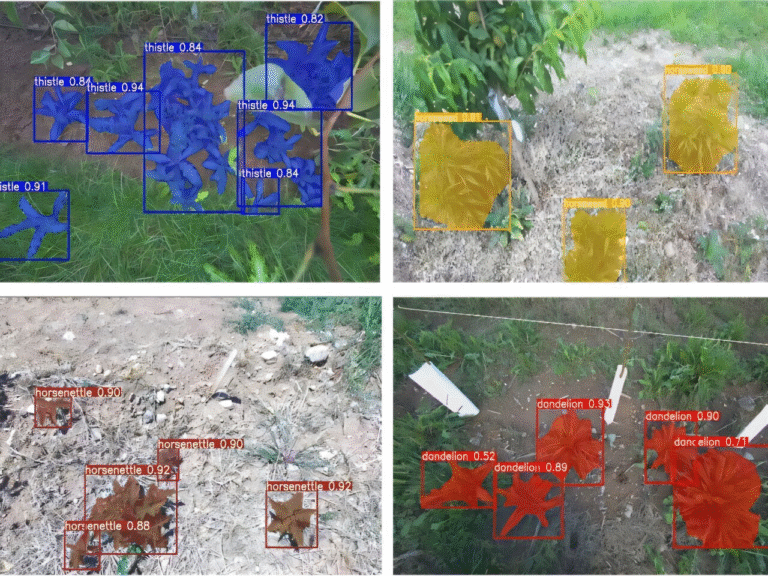

Researchers estimate that at least 11 species of vertebrate scavengers feed on these remains. Among them are Arctic foxes, ravens, ivory gulls, glaucous gulls, and snowy owls. An additional eight species are considered potential scavengers that may occasionally benefit, such as wolverines and wolves.

A Hidden Web of Dependence

One of the most striking findings of the study is how interconnected Arctic wildlife really is. The survival of scavenger species often depends on a steady supply of carrion, especially during the harsh winter months when other food sources are scarce. By providing such a large amount of biomass annually, polar bears act as a crucial link that maintains this hidden food network.

According to co-author Dr. Nicholas Pilfold from the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, the sea ice itself plays a vital role in this dynamic. It serves as a stable platform where scavengers can safely access carcasses. But as sea ice continues to disappear due to climate change, this natural delivery system of food is at risk.

In fact, the researchers found that in just two polar bear subpopulations where numbers have already declined, scavengers are losing more than 300 tons of food each year. This loss could have serious cascading effects on Arctic biodiversity.

Implications of Declining Polar Bear Populations

The study reinforces what climate scientists have long warned: the decline of sea ice threatens not only polar bears but the entire Arctic ecosystem. As temperatures rise, sea ice forms later in the season and melts earlier, reducing the time polar bears can spend hunting seals. With fewer successful hunts, fewer carcasses are left behind, which in turn means less food for scavengers.

This chain reaction could impact species such as the Arctic fox, which relies heavily on scavenging during lean months, and even bird populations that depend on carrion as a key seasonal food source.

Essentially, the loss of polar bears means the loss of a major nutrient pump that keeps Arctic food webs functioning.

How Scientists Measured the Scale of Carrion Supply

To arrive at their estimate of 7.6 million kilograms of carrion per year, the team analyzed decades of recorded observations of polar bear kills, carcass remains, and scavenging behavior across the Arctic. They then modeled average prey mass, estimated how often bears make kills, and calculated how much of each kill is typically consumed.

For instance, a ringed seal weighs about 50–70 kilograms, and researchers estimate that polar bears eat about 70% of the carcass, leaving the rest behind. Multiply that by thousands of successful hunts per year, and the numbers quickly add up.

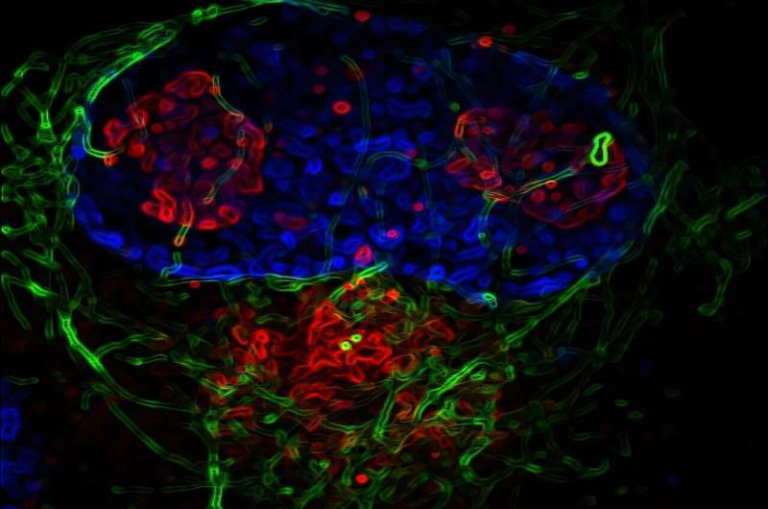

In some cases, researchers also conducted field experiments. At sites in Churchill, Manitoba, and Pond Inlet, Nunavut, they placed seal carcasses on the ice and used camera traps to observe which animals came to feed. The cameras captured multiple species visiting the carcasses, confirming that polar bear leftovers are a major source of energy for scavengers across different regions.

Why This Study Matters

The findings reshape our understanding of polar bears as ecosystem engineers. They are not just predators that regulate seal populations—they are also providers that distribute marine nutrients across the Arctic landscape.

Losing them would mean losing an important ecological service that no other species can replace. Unlike killer whales or other marine predators, polar bears hunt on sea ice and physically move prey out of the ocean, depositing remains in a location accessible to land-based species. No other predator performs this function on such a scale.

What This Means for Conservation

Conservation efforts have typically focused on protecting polar bears themselves—reducing greenhouse gas emissions, preserving sea ice, and minimizing human conflict. This study adds another layer of urgency: protecting polar bears means protecting an entire community of Arctic species.

If polar bear numbers continue to decline, the impacts could ripple through multiple levels of the food chain. Scavengers would lose a dependable food source, and the nutrient transfer between marine and terrestrial ecosystems could be severely weakened.

The research team stresses that conservation planning must consider ecosystem interdependence, not just individual species survival. Polar bears are, in essence, maintaining a food-sharing system that supports biodiversity across the Arctic.

A Broader Look at Arctic Food Webs

The Arctic is a finely balanced environment, where most species rely on seasonal cycles of abundance and scarcity. During winter, opportunities to feed are rare, so every carcass matters. Polar bears inadvertently fill a role similar to that of lions or wolves in other ecosystems—they leave behind remains that sustain scavengers when prey is otherwise difficult to find.

The decline of any top predator tends to reshape entire ecosystems. In Yellowstone, for example, the removal of wolves once caused elk populations to explode and vegetation to collapse. In the Arctic, the opposite could happen: the loss of polar bears could starve scavengers and weaken nutrient flows.

This research reminds us that conserving biodiversity isn’t just about protecting individual animals—it’s about preserving the invisible threads that connect them.

Research Paper: Predators and scavengers: Polar bears as marine carrion providers (Oikos, 2025)