Public Seed Banks Are Helping Researchers Fast-Track Corn Quality Research Beyond Yield

Corn breeding has traditionally focused on one dominant goal: higher yields. While yield remains important, researchers are increasingly aware that profitability and sustainability in modern agriculture depend on much more than how many bushels per acre a field produces. Corn today is expected to meet the needs of biotechnology, industrial manufacturing, nutrition, and global specialty markets, all of which require very specific grain qualities. A new study from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign shows that public seed banks may hold the key to accelerating this shift toward higher-quality corn—and doing so much faster than traditional breeding methods allow.

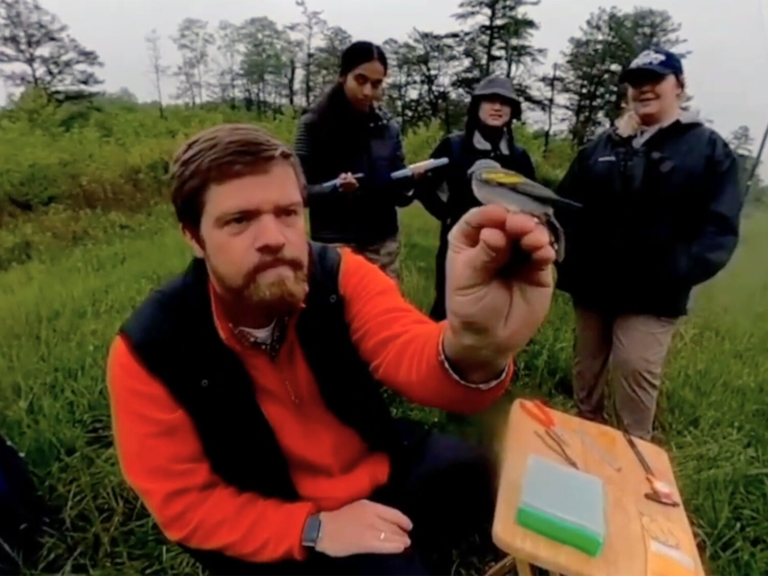

At the center of this research is corn breeder Martin Bohn, a professor in the Department of Crop Sciences at Illinois, along with his team, including doctoral student Christopher Mujjabi and undergraduate researcher Stephen Gray. Their work demonstrates that publicly available seed banks, when paired with modern genetic tools and data-driven analysis, can dramatically shorten the timeline needed to identify valuable traits in corn.

Why Corn Quality Matters More Than Ever

Corn is no longer just food for people or livestock. It plays a critical role in biofuels, bioplastics, industrial starches, specialty oils, and international export markets that demand specific grain compositions. Characteristics such as protein content, oil levels, starch structure, and kernel consistency directly affect how corn performs in these applications.

Traditionally, identifying and improving these traits requires years of field trials, extensive land use, and significant federal funding. Breeders must grow the same corn lines repeatedly across locations and seasons to separate genetic signals from environmental noise. This slow and costly approach limits how quickly new, high-quality corn varieties can reach farmers.

Tapping Into the Genetic Wealth of Public Seed Banks

The Illinois study takes a different approach by starting not in the field, but in the nation’s public seed banks. These seed banks store thousands of genetically diverse crop varieties that are freely available to researchers. In this project, the team analyzed nearly 1,000 maize inbred lines sourced from the USDA-ARS North Central Regional Plant Introduction Station (NCRPIS) in Ames, Iowa.

This collection is part of a broader national network of seed banks, including two major collections housed at the University of Illinois itself. Together, these repositories represent an enormous and largely untapped reservoir of genetic diversity that has accumulated over decades of plant breeding and collection efforts.

Despite their value, seed banks are often underused for quantitative genetics and breeding research, mainly because they usually provide limited seed quantities. Researchers may receive only around 100 seeds of a single genotype, which makes traditional replicated experiments impossible.

Using New Tools to Overcome Old Limitations

Rather than viewing this limitation as a barrier, the Illinois researchers treated it as a challenge to be solved with innovative analytical methods. The team used near-infrared spectroscopy, a high-throughput technique that allows rapid measurement of kernel composition traits without destroying the seeds. This approach enabled them to evaluate protein, starch, oil, and other compositional traits efficiently across hundreds of corn lines.

They combined these measurements with publicly available genomic data, allowing them to link physical kernel traits directly to genetic variation. Instead of focusing only on average trait values, the researchers also analyzed variance heterogeneity, which looks at how much traits vary within a genotype. This is important because consistency can be just as valuable as high performance in many industrial and food applications.

To analyze the data, the team applied genome-wide association studies (GWAS), variance-based genetic analyses, and genomic prediction models. These tools allowed them to pinpoint genetic regions that influence both the level and stability of kernel composition traits.

Proving That Unreplicated Data Can Still Be Reliable

One of the most important questions surrounding the study was whether meaningful genetic insights could really be extracted from unreplicated seed samples. To answer this, the researchers compared their findings with data from a large, replicated field experiment conducted by another research group in Minnesota.

That external study overlapped with 200 to 300 of the same maize lines used from the NCRPIS collection. When the Illinois team compared kernel composition measurements across both datasets, they found strong correlations, confirming that their unreplicated seed bank data captured real and reliable genetic signals.

This validation step was critical. It demonstrated that seed bank accessions—despite their small sample sizes—can still be used effectively for genetic discovery when paired with robust analytical methods and cross-study comparisons.

Discovering Known and New Genetic Targets

The study identified numerous genetic regions associated with kernel composition traits. Many of these regions aligned with previously known genes involved in protein, oil, and starch synthesis, reinforcing confidence in the results. At the same time, the analysis revealed new candidate genes that had not been previously linked to these traits.

These newly identified regions represent fresh breeding targets that can now be explored in more focused experiments. Instead of searching blindly across thousands of genotypes, breeders can use this information to zero in on the most promising material early in the breeding process.

A Shift in How Corn Breeding Can Begin

According to doctoral researcher Christopher Mujjabi, this work highlights a broader shift in breeding strategy. Rather than starting with years of expensive replicated field trials, researchers can now begin by mining existing gene bank collections. This early exploration helps breeders prioritize which lines are worth investing time and resources into.

By front-loading discovery with data from public seed banks, breeding programs can become faster, more targeted, and more efficient. Field trials still play a crucial role, but they can be reserved for validating the most promising candidates rather than screening thousands of possibilities.

Why Public Germplasm Collections Matter

Public seed banks are often described as genetic treasure troves, and this study shows exactly why. They preserve diversity that may no longer exist in commercial breeding programs, including traits related to resilience, nutritional quality, and processing performance.

When combined with high-throughput phenotyping, shared genomic datasets, and modern computational tools, these collections become powerful engines for crop improvement. This approach is especially important as agriculture faces challenges related to climate change, resource efficiency, and changing market demands.

Broader Implications for Agriculture

While this research focuses on corn, the implications extend far beyond a single crop. Many major food and industrial crops—such as wheat, rice, soybeans, and sorghum—also have extensive public germplasm collections. Applying similar pipelines could accelerate improvements across the agricultural landscape.

The study also reinforces the value of open-access data and public research infrastructure. Because the seed banks and genomic datasets used in this work are freely available, researchers worldwide can replicate, extend, and build upon these findings.

Looking Ahead

The Illinois team has developed a practical pipeline that allows researchers to explore what already exists in gene banks before launching large-scale experiments. This approach saves time, reduces costs, and increases the likelihood of success. By identifying interesting genetic material early, breeders can move more quickly toward developing high-quality, resilient corn varieties suited for tomorrow’s agricultural and industrial needs.

As the demand for specialized crops continues to grow, public seed banks may play an increasingly central role in shaping the future of global agriculture.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1002/tpg2.70131