Radar Research Reveals the Sky Is a Vast, Organized Ecosystem Full of Life

When people think about habitats on Earth, they usually picture forests, oceans, wetlands, or grasslands. Very few think about looking up. Yet new scientific research suggests that the lower atmosphere, the part of the sky closest to the ground, may actually be the largest and most overlooked habitat on the planet. Far from being empty space, the sky is now being recognized as a living, structured environment used by trillions of animals every single day.

A major study published in the journal Ecology presents compelling evidence that the sky functions as an organized ecological system, complete with daily rhythms, vertical layers, and predictable seasonal patterns. Using decades of weather radar data, researchers have mapped how birds, bats, and insects occupy and move through the airspace across North America, revealing a hidden world that has long escaped human attention.

The Lower Atmosphere as a Living Habitat

The study focuses on the troposphere, the lowest layer of Earth’s atmosphere, which extends from the ground up to about 10–12 kilometers. By volume, this layer is estimated to be five times larger than the oceans, making it an enormous potential habitat. Within this space, countless animals are constantly flying, migrating, feeding, and even sleeping while airborne.

Until recently, scientists lacked the tools to observe this activity at large scales. Individual observations, tagging studies, and visual surveys only captured fragments of the picture. What remained largely invisible was how animals collectively use the sky across entire continents and throughout the day and night.

That gap is now being filled by radar.

Using Weather Radar to Study Wildlife

The research team relied on data from the United States’ Next Generation Weather Radar network, commonly known as NEXRAD. This system consists of more than 140 radar installations spread across the country. While NEXRAD is primarily designed to track weather events like rain and snow, it also detects biological signals, including birds, bats, and insects in flight.

By analyzing over 100 million radar observations collected between 1995 and 2022, scientists were able to build an unprecedented, continent-wide view of aerial life. The data allowed them to measure daily activity cycles, identify vertical layers of movement, and determine how airspace use changes across seasons.

The result is one of the most comprehensive studies ever conducted on how animals use the sky.

Nighttime Dominates Aerial Movement

One of the most striking findings of the study is how strongly nocturnal aerial activity is. During the spring and autumn migration seasons, approximately 88% of all movement occurs at night. Summer shows a more balanced pattern, with about 54% of movement happening after sunset.

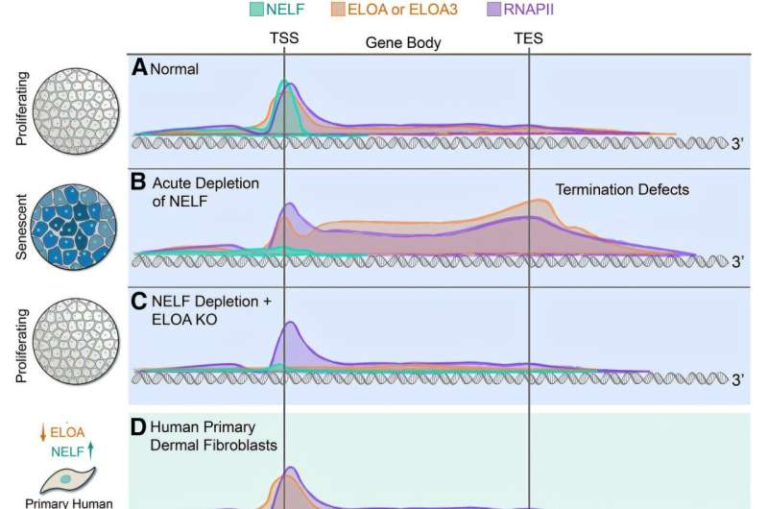

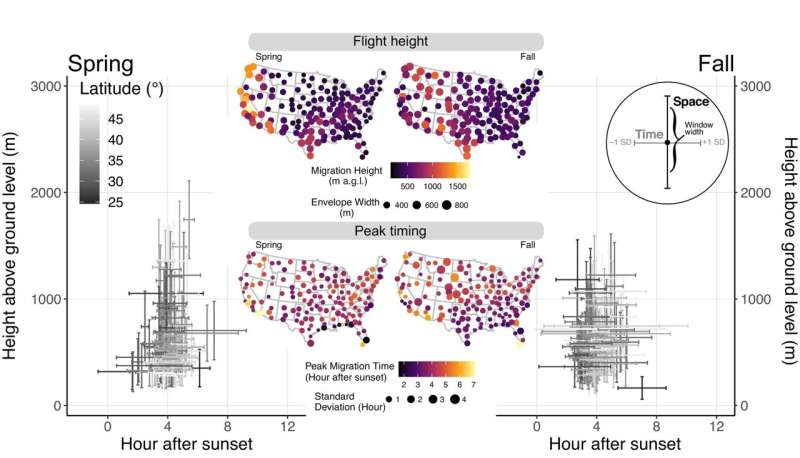

This overwhelming preference for nighttime flight is consistent across much of the continent. The data also shows that peak migration activity typically occurs about four hours after local sunset in both spring and autumn. These consistent timing patterns suggest that animals are responding to shared environmental cues such as light levels, temperature, wind conditions, and predator avoidance.

The sky, it turns out, follows a daily rhythm just like forests and oceans do.

A Structured Sky With Vertical Layers

The study also reveals that aerial movement is not randomly distributed by height. During peak migration periods, half of all airborne movement is confined within a vertical band about 516 meters thick, starting at roughly 355 meters above ground level.

This means the sky has layers, similar to depth zones in the ocean. Different species may favor different heights depending on wind conditions, energy efficiency, temperature, and foraging opportunities. These vertical structures remain surprisingly consistent across regions and seasons, indicating a shared ecological organization.

By mapping these height envelopes across the country, researchers were able to show that the sky is not just busy, but highly organized.

Seasonal Patterns Across the Continent

Using radar data from 143 NEXRAD sites, the team created detailed maps showing how airspace use changes throughout the year. Spring migration runs roughly from March 1 to June 15, summer from June 16 to July 31, and autumn migration from August 1 to November 15.

Spring and autumn show intense, concentrated nighttime movement, while summer displays more evenly distributed activity across day and night. These seasonal differences reflect breeding cycles, food availability, and long-distance migration strategies shared by many species.

Importantly, the study captured not just where migration happens, but when and how high, providing a much richer understanding of aerial ecology.

A Habitat With Less Competition Than Expected

One of the more intriguing insights from the research is the idea that the sky may be a rare habitat where competition plays a smaller role. Unlike land or water ecosystems, where space and resources are often tightly contested, the airspace is vast and continuously renewed.

Many species appear to share the sky simultaneously, migrating together in massive numbers without obvious signs of direct competition. This challenges traditional ecological assumptions and suggests that the sky operates under different rules than most other habitats on Earth.

Why This Matters for Conservation

Recognizing the sky as a living habitat has major implications for conservation and planning. Human activity in the airspace is increasing rapidly, with airplanes, wind turbines, drones, tall buildings, and artificial lighting all becoming more common.

Without understanding how wildlife uses the sky, these developments risk causing widespread disruption. Radar-based studies like this one provide essential data for reducing collision risks, improving wildlife-friendly infrastructure design, and developing better forecasting tools for migration events.

Protecting a habitat first requires acknowledging that it exists.

The Growing Field of Aeroecology

This research is part of a broader scientific movement known as aeroecology, which treats the atmosphere as a legitimate ecological domain. Aeroecologists study how airborne animals interact with weather, climate, and human structures, using tools like radar, acoustic monitoring, and satellite data.

As technology improves, researchers hope to combine radar data with species-specific methods, such as bioacoustics and tracking tags, to better understand how different animals share the sky.

Expanding Our View of Earth’s Ecosystems

The biggest takeaway from this study is a shift in perspective. The sky is not an empty space between destinations. It is a dynamic, living system, structured in time and space, and essential to the survival of countless species.

Thanks to decades of radar data, scientists can now see what was once invisible. This new view opens the door to smarter conservation strategies and a deeper appreciation of the life unfolding above us every night.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.70247