Rainforest Animals Are Using Tourist Walkways: What This Means for Conservation Design

A new study has uncovered something fascinating happening in the treetops of the Amazon rainforest: wild animals are using tourist canopy walkways as their own forest highways. Conducted by biologists from Binghamton University, the research reveals that arboreal mammals—those that spend much of their lives in trees—aren’t shy about taking advantage of man-made paths high above the forest floor.

This discovery offers a new perspective on how human-built structures might play an unexpected role in supporting wildlife movement, especially as deforestation continues to fragment habitats around the world. Let’s take a closer look at what the researchers found, how they did it, and why it matters for conservation efforts in tropical rainforests.

The Study Site: ACTS Field Station in the Peruvian Amazon

The research took place at the Amazon Conservatory for Tropical Studies (ACTS) Field Station, located within the Napo-Sucusari Biological Reserve, about 40 miles from Iquitos, Peru. The area is a pristine stretch of the Amazon with continuous canopy cover—meaning the trees are so close together that their branches form a nearly unbroken roof over the forest.

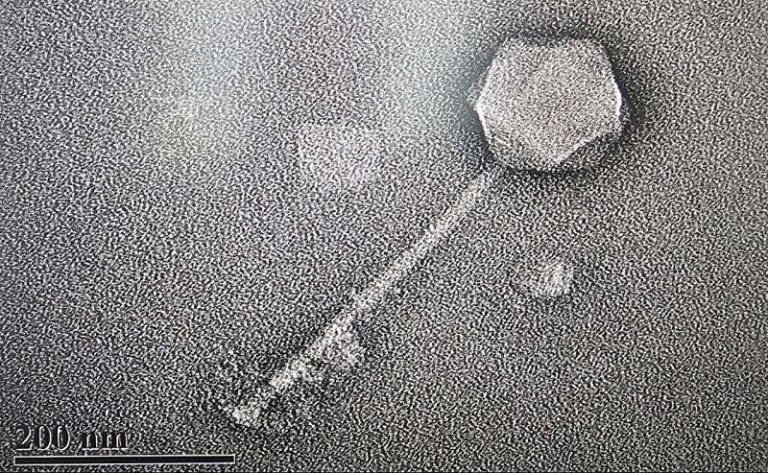

The ACTS canopy walkway system is one of the most remarkable of its kind in the world. It consists of platforms and bridges suspended 6 to 36 meters (20 to 118 feet) above the ground, originally designed for researchers and eco-tourists. But it turns out that humans aren’t the only ones enjoying the view from above.

The Amazon rainforest is home to around 427 mammal species, and over half of them (roughly 227) are arboreal—living most of their lives in the canopy. These include animals like sloths, monkeys, porcupines, and opossums, all of which depend on continuous treetop pathways for feeding, breeding, and safety.

How the Study Was Conducted

The study, titled “Arboreal mammal use of canopy walkway bridges in an Amazonian forest with continuous canopy cover,” was carried out by Justin Santiago, a graduate student at Miami University and Binghamton alumnus, along with Dr. Lindsey Swierk, Assistant Professor of Biological Sciences at Binghamton.

To understand how arboreal mammals used the walkways, the team installed four camera traps along different sections of the canopy bridges. These cameras recorded continuously over a three-week period, capturing any animal activity on or near the structures.

Each camera was placed at different heights—around 12, 21, 26, and 33 meters above ground—to cover various canopy layers. The researchers also measured environmental factors such as temperature, humidity, and wind speed across the forest’s vertical strata to see if weather patterns affected animal movement.

What the Cameras Captured

Over the course of the study, the cameras recorded 41 instances of arboreal mammals using the canopy walkway. Species identified included two-toed sloths, porcupines, opossums, and several types of monkeys. Notably, these animals were only seen using the walkways at night.

This nocturnal activity might partly reflect the natural habits of these species, many of which are active after dark. However, it may also indicate that animals avoid human presence during the day—especially since the walkway is frequented by tourists and researchers. Interestingly, outside of the formal study period, a sloth and a troop of saki monkeys were spotted using the walkway during the daytime, but only after the tourist season had ended and human activity had dropped.

The mid-canopy level (around 20–27 meters) saw the highest amount of traffic, suggesting that this height range might represent a “sweet spot” for arboreal crossings. The animals seemed to prefer using the bridge beams rather than the walkway platforms, likely because the beams resemble natural tree limbs more closely.

Why This Matters: Connectivity in Fragmented Forests

Although this study was conducted in a largely intact forest, its findings carry major implications for conservation in more fragmented landscapes. As deforestation and road construction continue to split forests into smaller patches, tree-dwelling mammals are at increasing risk. They often have to descend to the ground to cross open areas, exposing them to predators and road traffic.

Artificial canopy bridges—whether purpose-built for wildlife or repurposed from human infrastructure—can serve as safe corridors connecting isolated forest patches. The fact that these animals naturally adopt existing structures like tourist walkways shows that they are willing and able to use artificial routes if they provide the right conditions.

The research suggests that walkway design matters. Future structures could be built or modified with wildlife in mind by:

- Positioning bridges at mid-canopy height, where use is highest.

- Incorporating natural materials and beam-like features that mimic tree branches.

- Limiting human activity at night or in certain seasons to reduce disturbance.

This kind of design thinking could help prevent road deaths, improve gene flow between animal populations, and enhance the long-term resilience of forest ecosystems.

Beyond the Walkways: Understanding Arboreal Mammals

To appreciate the importance of canopy connectivity, it helps to understand why arboreal mammals are so specialized. Many of these species—such as sloths, tamarins, and porcupines—are physically adapted for life in the treetops. Their limbs, claws, and tails allow them to climb and balance with ease, but make ground travel difficult and dangerous.

For example, sloths move slowly and spend most of their time hanging upside down from branches. On the ground, they are nearly defenseless. Likewise, porcupines like Coendou ichillus and Coendou longicaudatus are expert climbers that use their prehensile tails for stability in the canopy. Even small marsupials, such as opossums, rely heavily on arboreal routes for accessing food and avoiding predators.

These creatures play crucial ecological roles too. By moving through the canopy, they help disperse seeds, pollinate flowers, and control insect populations—all essential functions for maintaining rainforest health. Ensuring their safe passage across fragmented habitats doesn’t just protect the animals themselves; it helps preserve the entire ecosystem.

Insights from the Amazon to the World

The concept of canopy bridges isn’t new. In other parts of the world, conservationists have built rope bridges and suspended tunnels over roads to help arboreal wildlife cross safely. For example:

- In Australia, rope bridges have been built for gliders and possums.

- In Costa Rica, conservationists have installed simple vine bridges to help monkeys cross fragmented areas.

- In India, the Meghalaya region has living root bridges, which, while human-made, double as passageways for both people and small animals.

What makes the Peruvian study so important is that it provides quantitative evidence—from camera trap data—showing that wild mammals will indeed use elevated human structures even when natural canopy connections already exist. This means that in fragmented forests, where natural bridges are missing, well-designed artificial ones could make a real difference.

What Comes Next

The researchers see this as just a starting point. Future studies could examine:

- How seasonal changes affect walkway use.

- Whether certain species become more or less active depending on human presence.

- How different bridge materials or designs influence which animals use them.

- Long-term effects on population connectivity and biodiversity in areas with canopy walkways.

While the ACTS site remains a research hub, the implications go far beyond the Amazon. As forests continue to shrink, the lessons learned here could help guide global conservation strategies for arboreal species everywhere.

Research Reference:

Santiago, J., & Swierk, L. (2025). Arboreal mammal use of canopy walkway bridges in an Amazonian forest with continuous canopy cover. Neotropical Biology and Conservation.

https://doi.org/10.3897/neotropical.20.e154791