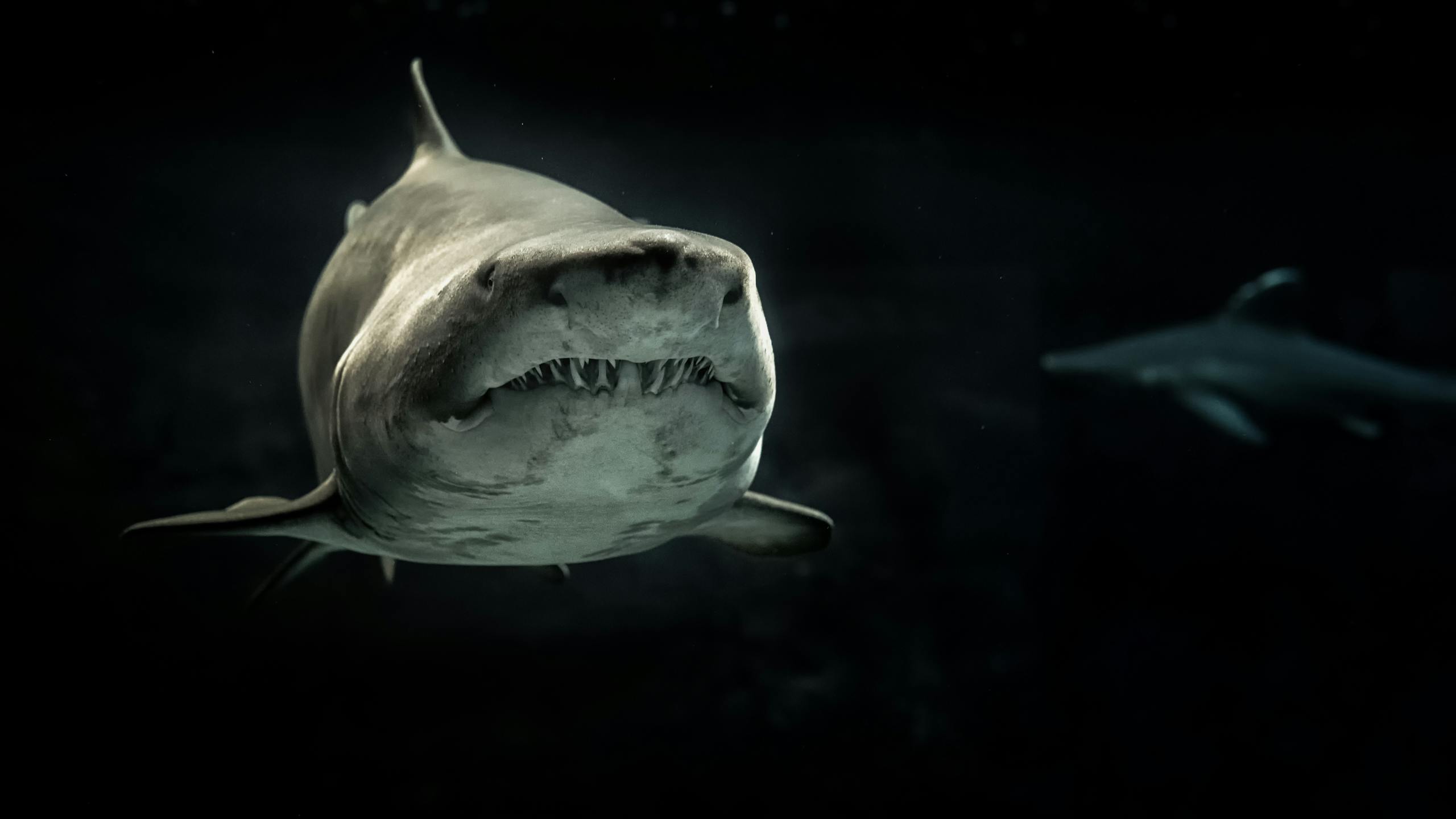

Remote Pacific Marine Reserves Reveal Thriving Shark Populations While Coastal Protected Areas Struggle

Remote marine protected areas in the Eastern Tropical Pacific are turning out to be some of the strongest remaining sanctuaries for sharks and other large predatory fish, offering a rare glimpse of what a healthy ocean once looked like. A major new scientific survey, one of the most comprehensive assessments ever conducted in this region, highlights a striking contrast: while remote island reserves such as the Galápagos, Malpelo, Clipperton, and Revillagigedo host some of the densest shark populations recorded globally, coastal protected areas in countries like Ecuador and Costa Rica show severe declines in predators and overall fish abundance.

This research, led by scientists from the Charles Darwin Foundation in collaboration with National Geographic Pristine Seas and several regional agencies, relied on Baited Remote Underwater Video systems (BRUVs) to document sharks and large predatory fish across seven marine protected areas (MPAs). The study included four oceanic MPAs—Galápagos, Malpelo, Clipperton, and Revillagigedo—and three coastal MPAs—Machalilla, Galera San Francisco, and Caño Island. These BRUV systems, which use underwater cameras baited with fish oil, allowed researchers to non-invasively observe species that are often difficult to monitor through traditional methods.

The results clearly show that the remote oceanic MPAs support abundant and diverse marine communities across all levels of the food web. These areas appear to function not only as strongholds for adult sharks, but also as important nursery zones. For instance, a large proportion of the Galápagos sharks recorded around Clipperton were juveniles, suggesting that this isolated atoll plays an essential role in early shark development. Meanwhile, the other island MPAs tended to show more large, mature sharks, which indicates that these areas serve as aggregation or foraging zones for adult populations. This kind of life-stage complementarity underscores how a network of MPAs can collectively safeguard different habitats required throughout a species’ lifespan.

The study also documented clear regional differences in predator communities. The critically endangered scalloped hammerhead shark (Sphyrna lewini) appeared more frequently in the southern MPAs, particularly the Galápagos and Malpelo. In contrast, the vulnerable silvertip shark (Carcharhinus albimarginatus) dominated sightings in the northern MPAs of Clipperton and Revillagigedo. These patterns likely emerge from variations in ocean currents, water temperature, and local food availability. Understanding such ecological distinctions is crucial because it means that each MPA hosts a unique marine community, and each requires management strategies tailored to its specific environmental conditions.

However, the optimism surrounding the remote islands is tempered by what is happening along the coast. In stark contrast to the oceanic MPAs, surveys from the coastal protected areas revealed very few sharks and noticeably lower fish abundance overall. Researchers describe this as a clear sign of an ecosystem under significant pressure. Many of these coastal sites once hosted large predators, but persistent fishing pressures—legal and illegal—have severely diminished those populations. The trend identified here aligns with the concept of fishing down the food web, where the removal of top predators pushes fishers to target smaller species. Over time, even these mid-level species decline, disrupting entire ecosystems and making recovery increasingly difficult.

This contrast highlights a broader issue: the term marine protected area can be misleading if the protection is not enforced. Across Mexico, Costa Rica, Panama, Colombia, and Ecuador, there are more than 77 MPAs, but they vary widely in the degree of protection they offer. Some allow extractive activities, others use mixed-use management, and a small proportion are truly fully protected no-take zones, where all fishing and resource extraction are strictly banned. The new research makes it clear that the no-take MPAs—especially those located far from human activity—are by far the most successful in preserving thriving marine communities. MPAs that permit fishing, even under regulation, simply do not achieve the same ecological outcomes.

The study also ties into global efforts to expand protected ocean areas. Currently, less than 10% of the world’s oceans are under some form of protection, and only 3% receive what scientists consider high-level, effective protection. The international goal, set by conservation organizations and many governments, is to protect 30% of the ocean by 2030. Achieving this would require establishing 300 new large, remote MPAs and roughly 190,000 coastal MPAs, according to researchers involved in the study. With only five years left to reach this target, the findings from the Eastern Tropical Pacific serve both as motivation and a warning: properly enforced MPAs work, but minimally protected areas offer little ecological value.

These results emerge from a series of multi-week expeditions conducted with partners across the Eastern Tropical Pacific, including the Malpelo Foundation in Colombia, Pelagios Kakunjá in Mexico and France, Osa Conservation in Costa Rica, and environmental ministries in Ecuador. Much of this work aligns with long-term conservation efforts led by groups such as National Geographic’s Pristine Seas project, which focuses on exploring and protecting some of the most pristine ocean locations on the planet.

From a broader ecological standpoint, sharks play a crucial role in shaping marine ecosystems. As apex predators, they help regulate fish populations, remove weak or diseased animals, and maintain balance among species at various trophic levels. When sharks decline, the effects ripple downward: prey species can become overabundant, herbivore populations may shift, and coral reefs and seamount ecosystems can undergo dramatic transformations. This is why the decline of sharks in coastal MPAs is so concerning—these ecosystems may not be able to stabilize themselves without the presence of top-down regulators.

Another important point that emerges from this research is the role of connectivity in marine conservation. Many species of sharks and migratory fish travel long distances across borders and between MPAs. Protecting only isolated pockets of habitat may not be enough. Instead, conservation success depends on creating networks of protected areas that collectively cover nursery grounds, feeding grounds, migration corridors, and breeding sites. The Eastern Tropical Pacific region, with its chain of oceanic islands, is particularly important in this regard.

This new study serves as a clear reminder that while the ocean faces intense pressures from overfishing, habitat degradation, and climate change, it is still possible to maintain or restore thriving marine ecosystems—when protection is genuine, strict, and science-based. Remote island MPAs show us what is possible. The challenge ahead is extending similar levels of protection to the coastal regions that need it most.

Research Source:

Relative abundance and diversity of sharks and predatory teleost fishes across Marine Protected Areas of the Tropical Eastern Pacific

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0334164