Researchers Uncover a New Gravity-Sensing Pathway That Helps Plants Grow in the Right Direction

Scientists at the University of Wisconsin–Madison have identified a previously unknown genetic pathway that helps plants sense gravity and orient their growth, revealing that plant gravitropism is far more complex than earlier believed. This discovery not only expands our understanding of how plants stay upright and organize their architecture but may also contribute to smarter crop breeding in the future. The new pathway centers on an unstudied gene called SLQ1, which becomes especially significant when another known group of gravity-related genes, known as LAZY, is disabled.

For years, plant biologists have known that LAZY genes play a core role in gravity detection. These genes help plant cells sense the direction of gravity and then coordinate the placement of growth hormones so that stems grow upward, branches extend outward, and roots stretch downward. When LAZY genes are turned off, plants lose their sense of direction entirely. Instead of growing vertically, they slump and spread along the soil surface, bending unpredictably. Because of this unusual behavior, such mutant plants are informally called LAZY plants.

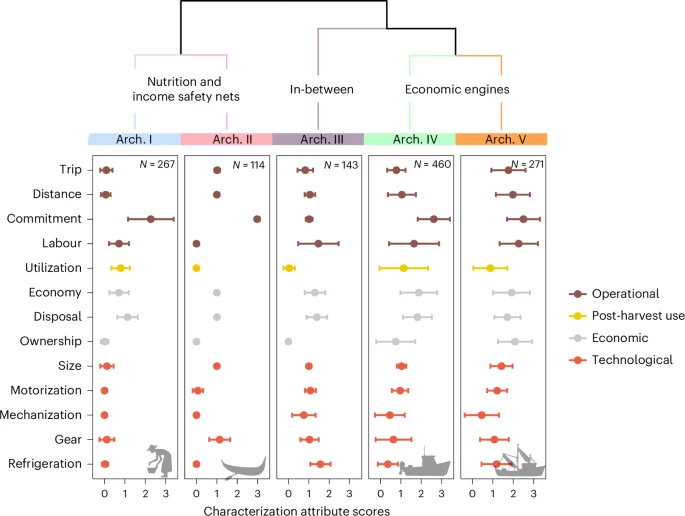

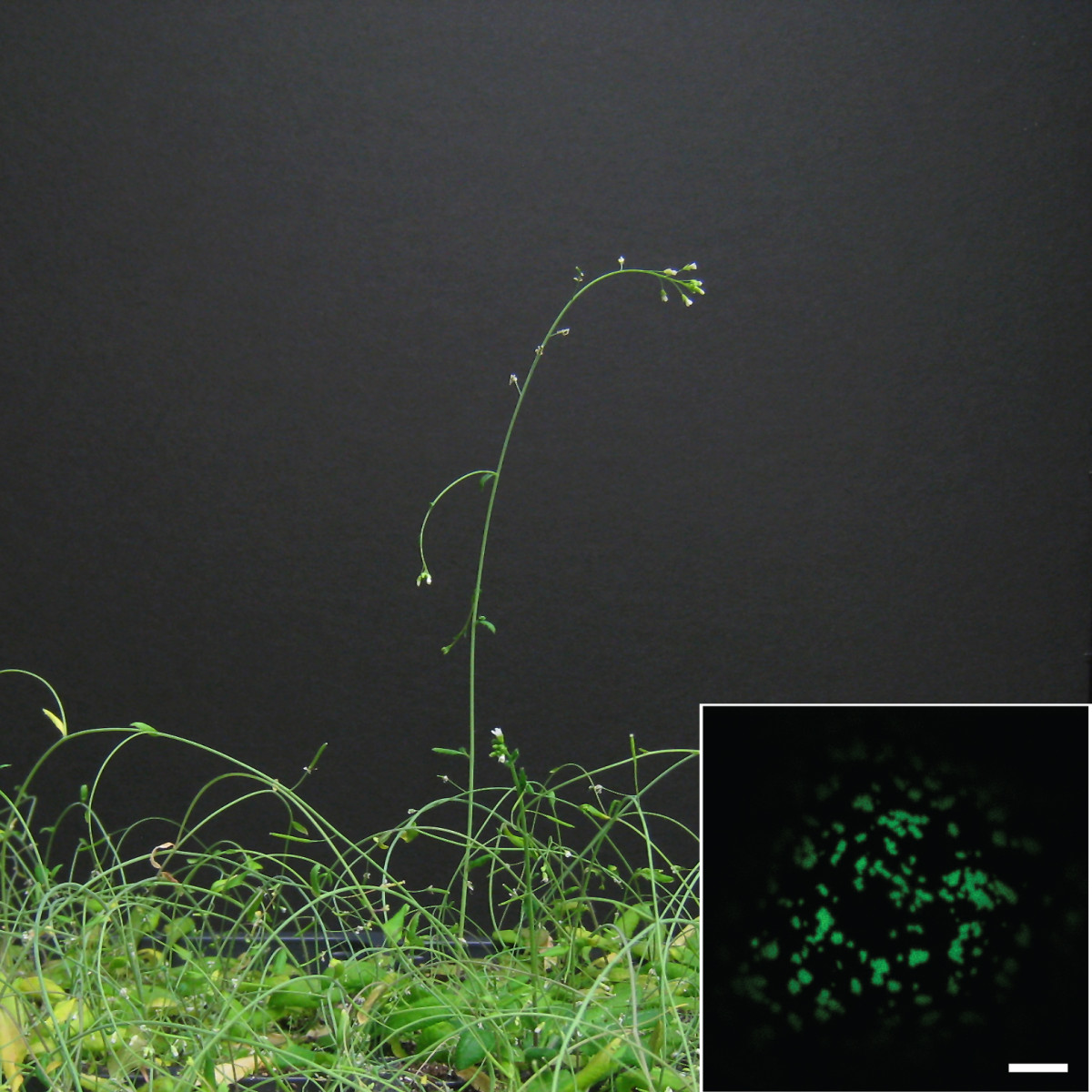

Researchers Edgar Spalding and Takeshi Yoshihara set out to investigate whether other gravity-detection pathways might exist alongside the LAZY system. Their approach was simple but bold: disable LAZY genes in the model plant Arabidopsis, then introduce thousands of random mutations to see if any of them restored normal growth. If a second pathway existed, a mutation might activate or disable something else that corrects the LAZY plant’s directional confusion.

After screening thousands of mutated plants, the team finally identified a gene they named SLQ1, short for Suppressor of LAZY Quadruple 1. Its discovery came from observing a surprising outcome. When both LAZY genes and the SLQ1 gene are switched off, the plants do not collapse along the ground. Instead, their stems lift upward again, resembling more typical plant growth. In other words, eliminating SLQ1 in a plant that already lacks LAZY genes partially restores the ability to grow upright. The researchers describe this result as a case where two wrongs really do make a right.

This unexpected finding revealed that plants use at least two independent pathways to detect gravitational direction. Importantly, these pathways operate in different areas of the cell and are not dependent on each other. The LAZY pathway affects specific cellular structures involved in directing growth hormones, while SLQ1 appears to work at endoplasmic reticulum–plasma membrane contact sites, locations where internal cell membranes meet the cell’s outer membrane. These sites are known to be involved in signaling processes, which suggests that SLQ1 may play a role in a separate signaling mechanism for gravity perception.

Why plants have more than one gravity-sensing pathway is still an open question. However, researchers suggest several possibilities. One is that the SLQ1 pathway may serve as a backup system, ensuring that growth orientation is preserved even if the main LAZY pathway fails. Another possibility is that these pathways work together under normal conditions, fine-tuning the shape and growth direction of the plant over time. Gravity is a constant environmental input, and plants benefit greatly from being able to adjust their architecture to maximize light capture, improve stability, and enhance nutrient uptake. Multiple pathways may offer added precision and resilience.

Spalding notes that the detailed interplay between these pathways remains unknown, and further research will be needed to determine exactly how each contributes to the plant’s final shape. But the takeaway is clear: gravity influences plant growth through a far more intricate molecular program than scientists previously realized.

Beyond its fundamental scientific interest, this new understanding of plant gravitropism could benefit agriculture. If breeders can manipulate how plants detect and respond to gravity, they may be able to engineer crops with optimized stem angles, stronger root systems, and more efficient branch structures. Such improvements could make fields easier to harvest, increase yield, or help plants withstand environmental stress. As global food demand increases, insights like these can contribute to designing crops that are better suited to modern agricultural challenges.

This work also reinforces why Arabidopsis remains such a valuable model organism. Its small genome and fast growth make it ideal for genetic screens. In this case, the researchers used a classic approach—mutagenesis and phenotype observation—to reveal a completely hidden layer of plant biology. They confirmed the identity and role of SLQ1 using modern genetic tools, including sequence mapping and CRISPR-based gene editing.

To place this discovery in context, it helps to understand how plants typically sense gravity. The widely accepted model involves specialized cells called statocytes found in roots and shoots. Inside these cells are dense, starch-filled organelles called statoliths. These organelles settle under the influence of gravity, much like tiny stones in a snow globe. Their position triggers molecular signals that redistribute plant hormones—especially auxin, which tells cells where to elongate. The result is controlled bending toward or away from gravity.

The LAZY genes operate within this framework by helping direct the movement of auxin. When LAZY genes are missing, auxin is distributed incorrectly, and the plant bends in the wrong direction or fails to bend at all. What makes the SLQ1 discovery surprising is that its influence appears outside this established statolith-auxin system. Its association with ER–plasma membrane contact sites hints at a signaling route separate from the traditional statolith model, suggesting that plants have greater redundancy or flexibility than expected.

Biologists have long known that gravitropism involves layers of complexity—from mechanical sensing to hormonal redistribution—but the identification of SLQ1 pushes that complexity further. It means the field must now consider multiple molecular circuits rather than a single dominant pathway. This challenges older assumptions and opens new experimental questions.

It is especially interesting that turning off both LAZY and SLQ1 restores upright growth. Rather than acting in a linear sequence, the two pathways seem to counterbalance each other. With LAZY disabled, SLQ1 may generate signals that override or misdirect growth, causing the plant to sprawl. But with both absent, the plant shifts back toward a more balanced growth state. Researchers will need to explore whether this effect reflects crosstalk between pathways, compensatory signaling, or the involvement of yet-unknown genes.

Overall, this discovery underscores how plants integrate environmental cues into their structural design. Gravity is a universal force, and all terrestrial plants must constantly interpret it. This study shows that they use more than one strategy to do so, each operating through different cellular machinery. Understanding these systems in detail will not only expand plant biology but may lead to innovations in crop design, agricultural efficiency, and even space-based plant cultivation where gravitational cues differ dramatically.

Research Paper:

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2510934122