Same Moves Different Terrain How Bacteria Navigate Complex Environments Without Changing Their Playbook

Bacteria may be tiny, but the way they move through the world is surprisingly sophisticated. A new study from researchers at the University of Chicago shows that many bacteria rely on the same basic movement strategy no matter how complex their surroundings become. Whether they are swimming freely in open liquid or squeezing through dense environments like soil, mucus, or biological tissue, these organisms do not switch tactics. Instead, they reuse a single, reliable “playbook” that adapts naturally to different physical conditions.

The research focuses on how bacteria move using flagella, the thin, whip-like structures that rotate to propel them forward. For decades, scientists have studied bacterial motion primarily in simple, open liquids. But bacteria rarely experience such clean conditions in real life. They inhabit crowded, messy environments filled with obstacles. This new work shows that what looks like different movement behaviors in those settings is actually the same underlying program playing out under different constraints.

The classic run-and-tumble model of bacterial movement

Some of the most well-known bacteria, including E. coli and Salmonella, move using a pattern called run-and-tumble. In this mode, a bacterium swims forward in a relatively straight line during a “run,” then briefly stops to reorient itself during a “tumble” before heading off in a new direction.

This strategy works extremely well in open water. It allows bacteria to explore their environment efficiently and respond to chemical signals, such as moving toward nutrients or away from toxins. Because of how effective and widespread this behavior is, run-and-tumble has become the standard model for bacterial motility taught in biology and physics.

However, most natural environments are not wide open. Soil particles, tissue fibers, mucus networks, and other structures create tight, irregular spaces. In such conditions, bacteria cannot always complete long, uninterrupted runs.

Why real-world environments complicate bacterial motion

Researchers have long known that bacteria often live in confined and crowded spaces. Inside the human gut, for example, bacteria must navigate through thick mucus and soft tissues. In soil, they encounter tightly packed particles with irregular gaps. These environments physically interfere with motion, making it harder for bacteria to swim smoothly.

Previous studies suggested that bacteria might use a different strategy under these conditions. In 2019, researchers studying E. coli moving through dense hydrogels described a behavior they called hop-and-trap. In this pattern, bacteria appeared to get stuck against obstacles, remain trapped for a while, and then suddenly hop through an opening once they found a way out.

This raised an important question. Were bacteria actually switching to a new movement program in tight spaces, or was something else going on?

Building a controlled maze for bacteria

To answer that question, Jasmine Nirody, an assistant professor of Organismal Biology and Anatomy at the University of Chicago, and her team designed a clever experiment. They used microfluidic devices, which are small silicon chips that allow scientists to control and observe the flow of tiny amounts of liquid with extreme precision.

The team created microfluidic chips filled with arrays of microscopic pillars. By changing the spacing and randomness of these pillars, they were able to simulate environments ranging from nearly open space to highly confined, maze-like terrain. These setups closely resemble the kinds of complex environments bacteria encounter in nature, such as soil or biological tissues.

They then tracked how E. coli bacteria moved through these artificial landscapes.

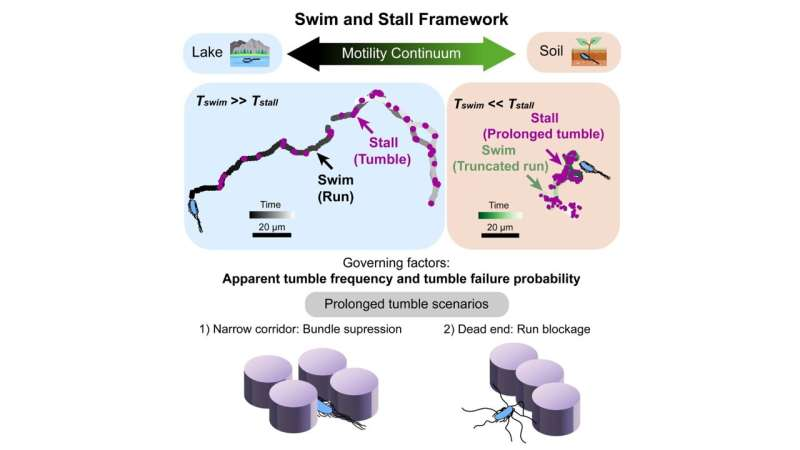

From run-and-tumble to swim-and-stall

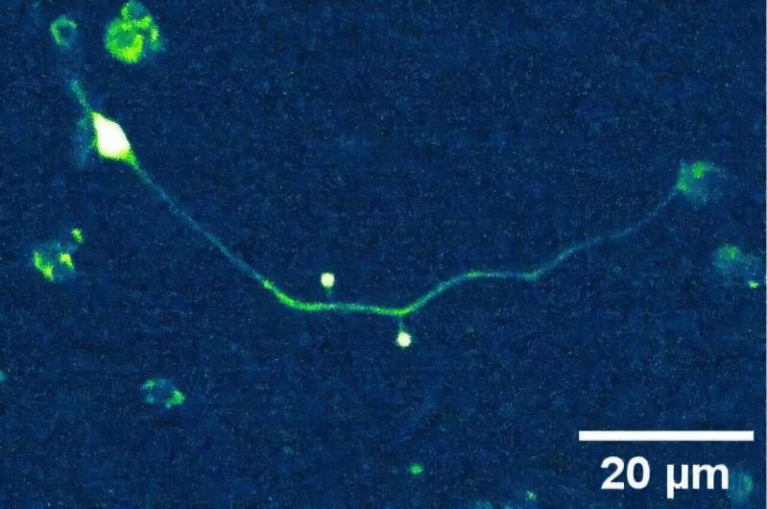

In open regions of the device, the bacteria behaved exactly as expected. They followed the familiar run-and-tumble pattern, swimming forward and periodically reorienting themselves.

As the environment became more crowded with pillars, their movement started to look different. Runs became shorter because bacteria frequently bumped into obstacles. Tumbling phases appeared longer, especially when bacteria became temporarily stuck and had to reorient multiple times to escape.

The researchers described this behavior as swim-and-stall. To the naked eye, it looks quite different from classic run-and-tumble or previously described hop-and-trap motion. But a closer analysis revealed something important. The bacteria were not changing how often they attempted to tumble, nor were they actively altering their internal movement rules. They were executing the same program as always. The environment was simply interfering with their success.

In other words, the bacteria were not doing something new. They were failing differently because of physical constraints.

Simulations confirm the experimental results

To test whether this explanation held up, the team ran mathematical simulations. They modeled bacteria using the same run-and-tumble rules in both open and confined environments. When obstacles were added to the simulated space, the virtual bacteria showed the same swim-and-stall behavior observed in the lab experiments.

The match between simulations and experiments was striking. It confirmed that no new behavioral program was required to explain what was happening. The apparent differences in motion emerged naturally from the interaction between a fixed movement strategy and a changing physical environment.

A simple analogy makes it clear

One way to understand this is to think about a person walking. Walking through dry, open ground looks very different from walking through thick mud. In mud, steps are shorter, movement is slower, and there is more twisting and struggling. But the person is still using the same basic walking motion.

Bacteria behave in much the same way. The underlying movement pattern does not change. Only the outcome does.

Evolutionary efficiency in bacterial design

From an evolutionary perspective, this finding makes a lot of sense. Bacteria are simple organisms with limited resources. Developing multiple genetic programs to handle every possible environment would be costly and inefficient.

Instead, bacteria appear to rely on a single baseline strategy that works reasonably well across a wide range of conditions. Rather than constantly sensing their surroundings and adjusting how often they tumble or how long they run, they let the environment shape the results of the same basic behavior.

This “good enough everywhere” approach is far cheaper than trying to optimize movement for every specific situation. Over evolutionary time, that efficiency likely gave bacteria a strong advantage.

Why this research matters

Understanding how bacteria move in realistic environments has implications far beyond basic biology. In medicine, it helps explain how pathogenic bacteria spread through tissues and mucus. In environmental science, it improves models of how microbes move through soil and porous materials. In physics and engineering, it offers insights into active matter systems and could inspire new designs for microscopic robots that function reliably in complex environments.

Perhaps most importantly, the study reminds us that behavior does not always need to be complex to be effective. Sometimes, the same simple rules, applied consistently, are enough to handle a messy and unpredictable world.

Extra context how bacteria sense and move

Bacterial motility is closely tied to chemotaxis, the ability to sense and respond to chemical gradients. During runs, bacteria sample their environment and compare chemical concentrations over time. If conditions improve, they extend their runs. If conditions worsen, they tumble more often.

The new findings suggest that even in crowded environments, this sensory system remains unchanged. Physical obstacles may limit how far bacteria can move, but the internal decision-making process stays the same. This reinforces the idea that bacterial behavior is remarkably robust, even when the environment is not.

The bigger picture of active matter

Bacteria are a classic example of active matter, systems made up of self-propelled units that consume energy to move. Studying how bacteria navigate disorder helps scientists understand other active systems, from synthetic microswimmers to groups of cells moving during development.

By showing that complex motion patterns can emerge without complex rules, this research adds an important piece to that broader puzzle.

Research paper: https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PRXLife.1.013002