Scientists Are Learning How to Speed Up Enzymes to Treat Disease Instead of Just Blocking Them

Enzymes are the core molecular engines of life. They drive nearly every chemical reaction inside our bodies — building molecules, breaking them down, copying DNA, digesting food, and keeping cells running smoothly. For decades, modern medicine has relied heavily on one main strategy when enzymes are involved in disease: blocking them. If an enzyme is helping cancer grow or allowing a virus to replicate, scientists design drugs that slow it down or shut it off entirely.

But a new shift is quietly taking place in biomedical research. Scientists are now asking a different — and far more complicated — question: What if some diseases aren’t caused by enzymes doing too much, but by enzymes doing too little? And if that’s the case, can we actually make enzymes work faster in a controlled and safe way?

Researchers at Rockefeller University, led by chemist and cell biologist Tarun Kapoor, are exploring exactly this idea. Their work highlights how much remains to be learned about enzyme behavior and why activating enzymes may become an important new frontier in drug development.

Why Blocking Enzymes Became the Go-To Strategy

Blocking enzymes has been a successful and reliable approach for a simple reason: it’s comparatively easy. Enzymes are proteins with specific shapes, and many drugs work by wedging themselves into key regions of those shapes, preventing the enzyme from functioning normally. This strategy has produced life-saving treatments, especially in cancer therapy, infectious disease, and inflammatory disorders.

Kapoor’s own scientific career was deeply rooted in this approach. His early training focused on designing small-molecule inhibitors — compounds that interfere with protein function. Later, his lab became well known for developing inhibitors that disrupt cell division, a process frequently targeted in cancer chemotherapy. Over two decades, his lab produced influential work, and many former trainees went on to become professors continuing research in that same field.

But after years of refining methods to stop enzymes, Kapoor began to wonder whether the same scientific tools could be used in a completely different way.

The Much Harder Problem of Making Enzymes Faster

Stopping an enzyme is a bit like stopping a bicycle. There are countless ways to do it — jam the wheel, cut the chain, or block the pedals. Making that same bicycle go faster, however, is far more delicate. Speed it up too much and it may crash, wobble, or break. You need to understand how the bike is built, how it balances, and where its gears are.

Enzymes work in much the same way. They are dynamic molecules that constantly change shape as they carry out chemical reactions. Blocking them often requires brute-force disruption. Speeding them up, on the other hand, demands deep knowledge of their mechanics, including how they move, how they change shape, and how their internal timing works.

This level of understanding can only come from basic science research, not quick fixes.

A New Focus on ATPase Enzymes

Kapoor’s lab turned its attention to a family of enzymes known as ATPases. These enzymes use ATP — the cell’s energy currency — to perform mechanical work. ATPases are involved in many essential processes, including protein transport, immune function, cellular cleanup, and even viral replication.

Crucially, in several diseases, ATPases are present but not working efficiently enough. Rather than being overactive, they are sluggish.

One ATPase in particular caught the team’s attention: VCP, or valosin-containing protein.

Why VCP Matters for Brain Health

VCP plays a central role in protein quality control. Cells are constantly producing proteins, and just as constantly disposing of ones that are damaged, misfolded, or no longer needed. VCP helps determine whether a protein should be recycled or destroyed, and it prepares those proteins for the appropriate pathway.

When VCP is impaired, proteins that should be cleared away begin to accumulate. Over time, this buildup can damage cells, especially neurons. Certain mutations in the VCP gene cause a rare but devastating condition marked by progressive neurodegeneration and dementia.

Importantly, in these patients, VCP isn’t completely broken. It’s still present and still active — it just works too slowly.

That distinction makes all the difference.

Searching for Molecules That Speed VCP Up

Because no one knew how to control the speed of VCP, Kapoor’s team started with an unbiased screening approach. They tested roughly 30,000 drug-like compounds in laboratory experiments, using purified VCP protein to see whether any compound could increase its activity.

A small number of promising compounds emerged. The team then refined these molecules using chemical modifications, improving their ability to enhance enzyme activity. This was an encouraging sign that VCP could, in fact, be activated rather than inhibited.

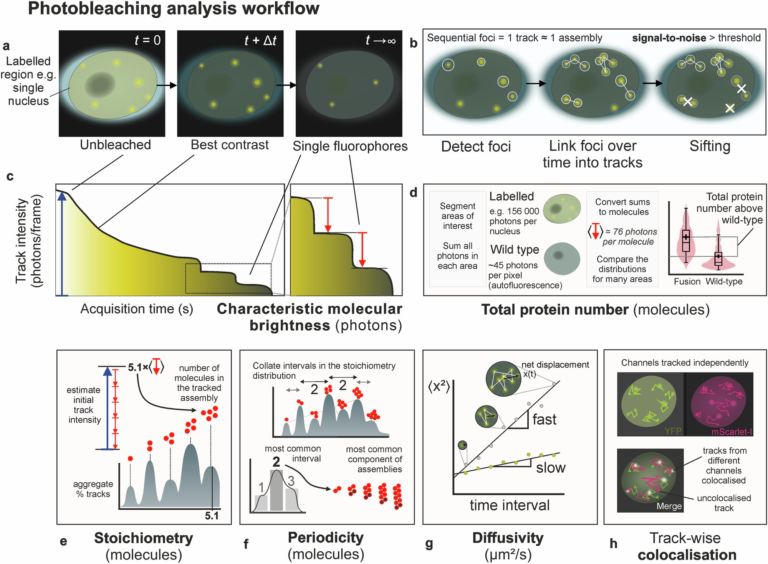

But the biggest breakthrough came when the researchers turned to cryo-electron microscopy, a technique that allows scientists to visualize proteins at near-atomic resolution.

Discovering a Molecular “Gearbox”

Using cryo-electron microscopy, the team was able to see exactly where the activating compounds were binding on the VCP enzyme. Surprisingly, the compounds were not interacting with the main active site. Instead, they bound to a distinct region that acted like a gearbox, shifting the enzyme into a higher-performance state.

By binding to this site, the compound changed how VCP moved through its normal cycle, allowing it to process proteins more efficiently without disrupting its core function.

This discovery provided a powerful insight: enzymes may contain hidden regulatory regions that can be targeted to fine-tune their speed, rather than simply turning them on or off.

Why This Matters Beyond a Single Disease

The specific regulatory “gearbox” found in VCP may not exist in the same form in other enzymes — and that’s actually a good thing. Drug developers want compounds that target one specific enzyme without accidentally speeding up others throughout the body.

However, the broader conceptual framework developed by Kapoor’s lab is likely to be widely applicable. Many diseases are caused by loss of function, where a protein is present but underperforming. This can happen when a person has only one working copy of a gene, or when mutations reduce efficiency rather than eliminating activity altogether.

There are already examples of this approach reaching the clinic. One drug currently in trials for heart failure works by improving the performance of an enzyme involved in heart muscle contraction, helping the heart pump more effectively.

Why AI Isn’t Enough Yet

Artificial intelligence tools like AlphaFold have revolutionized structural biology by predicting what proteins look like. However, Kapoor emphasizes that structure alone isn’t enough when it comes to enzyme activation.

Enzymes are not static objects. They are constantly shifting, bending, and cycling through multiple shapes as they work. Understanding how to speed them up requires capturing these dynamic movements, not just a single snapshot.

That’s why Kapoor’s lab relies on a combination of experimental methods: biochemistry to measure reaction speeds, structural biology to visualize binding sites, and cellular studies to observe real-world effects.

A New Frontier in Drug Discovery

For decades, enzyme inhibitors dominated pharmaceutical research. Enzyme activators, by contrast, remain relatively rare. But that may change as scientists gain better tools and deeper understanding of enzyme mechanics.

If researchers can successfully learn how to safely and precisely increase enzyme activity, it could open up entirely new treatment options for neurodegenerative disorders, metabolic diseases, certain cancers, and beyond.

The work is challenging, slow, and highly technical — but it represents a shift toward helping cells function better, rather than simply shutting things down. And in some diseases, that subtle difference could make all the difference.

Research paper reference:

https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.10.02.560478v1.full.pdf