Scientists Develop a Speed Scanner That Can Test Thousands of Plant Gene Switches at Once

Modern agriculture exists because humans learned how to shape plants to suit our needs. Long before gene editing tools existed, people selected seeds from plants that grew faster, produced larger harvests, or survived harsh conditions. Over time, this selective breeding slowly rewired how plant genes behaved. Today, scientists can directly edit DNA using powerful tools like CRISPR, but even with these advances, changing how plant genes are switched on or off remains surprisingly slow and complex.

A new technology developed by researchers at the Joint BioEnergy Institute (JBEI), working with UC Berkeley and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, aims to change that. The method, called ENTRAP-seq, functions like a high-speed scanner for plant gene switches, allowing scientists to test thousands of transcription regulators simultaneously inside plant cells. This represents a major leap forward in understanding and controlling plant gene expression.

Why Gene Switches Matter More Than You Might Think

Most traits that make crops useful—such as yield, flowering time, drought tolerance, disease resistance, and stress survival—are not controlled simply by whether a gene exists. Instead, they depend on how strongly a gene is expressed, when it turns on, and how long it stays active. These behaviors are governed by proteins known as transcription regulators.

Transcription regulators act like dimmer switches, not simple on/off buttons. They can shut a gene down entirely or finely adjust how much of a product the gene produces. Over thousands of years, agriculture has relied heavily on natural variations in these regulators. For example, early wheat varieties with larger grains emerged because certain gene regulators increased the expression of genes controlling grain size.

Despite their importance, transcription regulators remain poorly understood in most plants. Even in well-studied species, scientists often know which gene controls a trait but not how to tweak its expression safely and effectively. Traditional methods for studying these regulators are slow, labor-intensive, and usually require growing entire plants or leaves for each experiment.

What ENTRAP-seq Actually Does

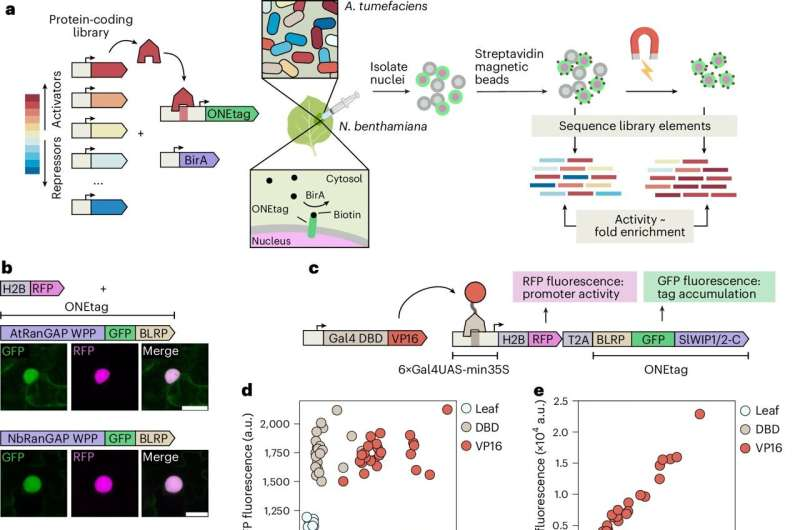

ENTRAP-seq solves this problem by shrinking gene regulation experiments down to the single-cell level. Instead of testing one transcription regulator at a time, the system tests thousands in parallel inside individual plant cells.

The process begins by creating a library of thousands of DNA sequences, each encoding a different transcription regulator or variant. These sequences are loaded into a plant-infecting bacterium, commonly used in plant biotechnology to deliver genetic material into cells. Each bacterium carries instructions for one specific regulator.

Researchers then inject this bacterial library into a plant leaf. Each bacterium transfers its DNA into a single plant cell, meaning every cell produces a different transcription regulator variant. As a result, thousands of unique regulatory experiments are happening at once inside the same leaf.

Alongside these regulators, scientists insert a synthetic target gene designed to report whether a regulator activates or represses gene expression. If a regulator activates transcription, the target gene produces a protein that binds to a magnetic tag and accumulates in the cell nucleus.

Using magnets, researchers can physically isolate only the cells where gene activation occurred. They then sequence the DNA inside those cells to identify exactly which transcription regulators caused the effect. This direct link between regulator identity and gene activity is what makes ENTRAP-seq so powerful.

A Massive Jump in Speed and Scale

The speed difference compared to traditional methods is dramatic. In a previous large-scale study, researchers spent two full years with two people working full-time to characterize around 400 plant transcription regulators using one-by-one experiments. With ENTRAP-seq, similar—and even more complex—analyses can be completed in just a few weeks.

To demonstrate this capability, the research team focused on a transcription activator involved in controlling flowering time in Arabidopsis, a widely used model plant. They created 350 mutated versions of the protein and rapidly screened which variants increased or decreased flowering-related gene activity. This level of detail and speed would have been nearly impossible using conventional approaches.

Combining Biology With Artificial Intelligence

The ENTRAP-seq study also highlights a growing partnership between machine learning and experimental biology. Before running their experiments, researchers used an AI model designed to predict DNA sequences capable of acting as gene activators across many organisms.

While this model helped prioritize promising regulators, its accuracy has been limited by a lack of real-world training data. ENTRAP-seq directly addresses this bottleneck by generating large, high-quality datasets on transcription regulator behavior in plants. These datasets can be fed back into AI models, improving predictions and accelerating future discoveries.

This creates a positive feedback loop: better models identify better candidates, faster experiments generate more data, and improved data further refines the models.

Why This Matters for Crop Engineering

One of the biggest challenges in plant biotechnology is precision. Editing a gene without understanding its regulatory context can lead to unintended side effects, such as stunted growth or reduced fertility. By mapping how transcription regulators behave, scientists gain a fine-grained control system for plant traits.

With ENTRAP-seq, researchers can begin cataloging which gene switches exist in a plant genome, whether they act as activators or repressors, and how far their activity levels can be safely pushed. This opens the door to designing crops with higher yields, better stress tolerance, and improved resilience to climate change—all without introducing foreign genes.

The method also allows exploration of transcription regulators from unexpected sources, including plant viruses, which often contain powerful regulatory proteins evolved to hijack host cells efficiently.

Broader Scientific and Industrial Impact

Beyond agriculture, ENTRAP-seq has implications for biofuel production, synthetic biology, and plant-based manufacturing. Understanding how to precisely control gene expression could help optimize plants used to produce renewable fuels, biodegradable materials, or valuable chemicals.

Because the technology is fast, scalable, and adaptable, it may become a standard tool for plant biology research. The method is also being made available for licensing through Berkeley Lab, signaling potential commercial applications.

A New Era of Gene Regulation Research

ENTRAP-seq represents more than just a faster experiment. It changes how scientists approach plant gene regulation entirely. Instead of guessing which regulators matter and testing them slowly, researchers can now scan entire regulatory landscapes at once. This shift could finally bring gene expression control in plants to the same level of sophistication seen in other areas of biotechnology.

As scientists continue refining this approach, the once-hidden switchboards controlling plant life may soon become fully visible—and adjustable.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41587-025-02880-w