Scientists Discover a Hidden RNA Aging Clock in Human Sperm That May Affect Future Generations

Scientists have long known that increasing paternal age is linked to higher health risks for children, including conditions like obesity, stillbirth, and neurodevelopmental disorders. However, the biological reasons behind these risks have remained unclear. A new study from University of Utah Health, published in The EMBO Journal, now points to a surprising and previously hidden factor: an RNA-based aging clock in human sperm.

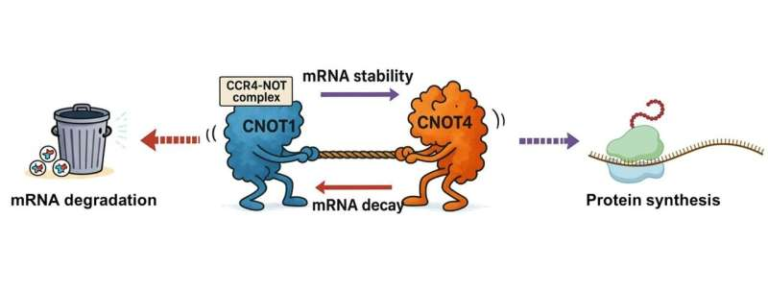

Most earlier research on paternal aging has focused on DNA mutations that accumulate in sperm over time. While DNA is undeniably important, sperm also carries a wide variety of RNA molecules, which help regulate early development after fertilization. This new research shows that these RNAs change in a predictable, age-related way, forming what researchers describe as a molecular “clock” that tracks sperm aging in both mice and humans.

Why Sperm RNA Matters More Than We Thought

RNA in sperm has often been overlooked because it is harder to study than DNA. Yet previous work from the same research group showed that sperm RNA can be influenced by a father’s diet, environment, and lifestyle, and that these changes can affect offspring health.

The challenge has always been detection. Many sperm RNAs are chemically modified, making them invisible to standard RNA sequencing tools. To overcome this, the research team developed an advanced sequencing method called PANDORA-seq, designed specifically to reveal these hidden RNA molecules.

Using this technique, scientists uncovered patterns that had never been seen before—patterns that change gradually with age and then suddenly shift dramatically at midlife.

The Discovery of an “Aging Cliff”

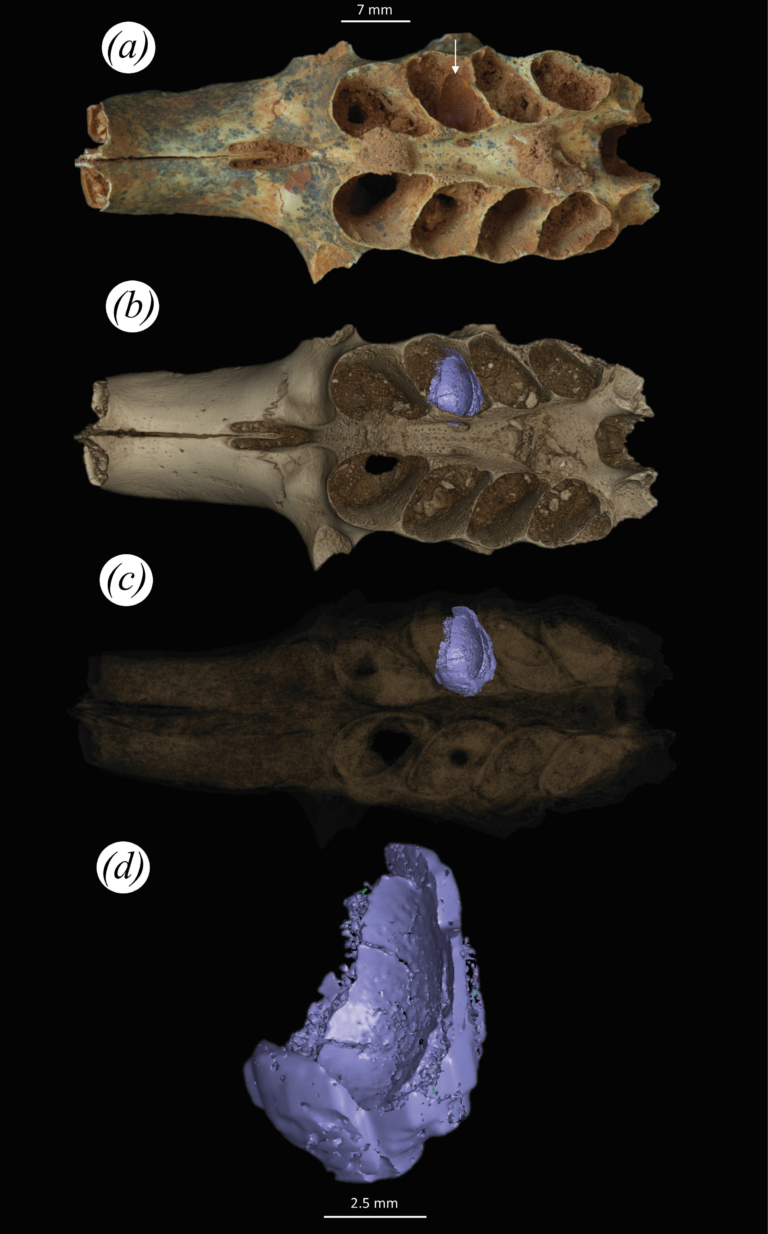

When researchers analyzed sperm from mice, they observed a striking phenomenon. Between 50 and 70 weeks of age, mouse sperm underwent a sharp and dramatic transition in RNA composition. The team refers to this as an “aging cliff.”

Before this point, RNA changes occurred gradually. Afterward, the RNA profile shifted rapidly and distinctly, suggesting a fundamental change in sperm biology at midlife.

Even more compelling, the same gradual RNA changes were later found in human sperm, strongly suggesting that this aging mechanism is evolutionarily conserved across species.

A Molecular Clock Made of RNA

The most surprising finding was the nature of these RNA changes. Scientists expected that, like DNA, RNA would become shorter and more fragmented with age. Instead, they observed the opposite.

As males age, certain sperm RNAs—especially ribosomal RNA-derived small RNAs (rsRNAs)—become longer, while shorter fragments become less common. This progressive length shift acts like a molecular clock, quietly accumulating over time until it reaches the midlife “cliff.”

These changes were consistent in both mice and humans, reinforcing the idea that sperm RNA length can serve as a biological marker of aging.

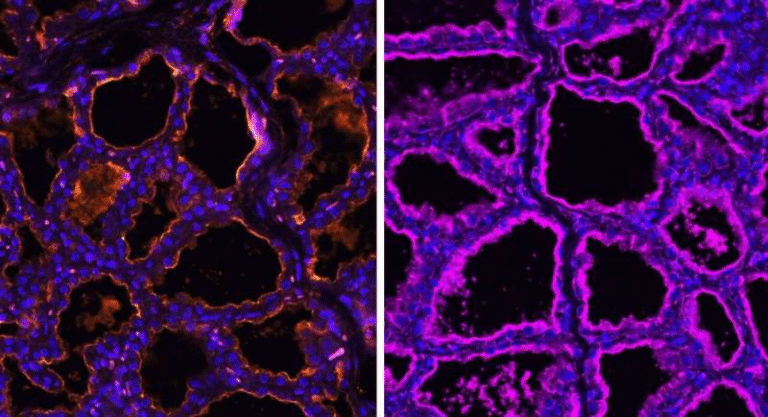

Why the Sperm Head Holds the Key

Another critical detail is where these RNA changes occur. The researchers discovered that the signal was specific to the sperm head, the part of the sperm that actually enters the egg during fertilization.

When scientists analyzed whole sperm cells, the signal was obscured by RNA from the sperm tail, which has a much noisier RNA profile. By isolating and sequencing only the sperm head, the researchers were able to clearly detect the age-related RNA shift.

This detail matters because it shows that the RNA changes are not random degradation, but precisely localized to the part of sperm that contributes directly to embryonic development.

Testing the Biological Impact of “Old RNA”

To understand whether these RNA changes actually matter, the researchers conducted functional experiments. They introduced a mixture of RNA from older sperm into mouse embryonic stem cells, which closely resemble early embryos.

The results were striking. The cells showed altered gene expression patterns linked to metabolism and neurodegeneration. While this does not prove that older fathers will have children with these conditions, it strongly suggests a mechanistic pathway by which sperm RNA could influence offspring health.

In other words, sperm RNA is not just a passive passenger—it may actively shape how early development unfolds.

From Mouse Models to Human Validation

Confirming these findings in humans required access to high-quality sperm samples across a wide age range. This was made possible by the University of Utah’s andrology and sperm bank resources, which allowed researchers to directly compare mouse and human data.

The discovery that the same RNA aging patterns exist in humans marks an important step toward translational andrology, the field focused on applying basic reproductive science to clinical practice.

What This Means for Reproductive Health

This research does not suggest that older men should avoid having children. Instead, it adds important nuance to our understanding of male fertility and reproductive aging.

In the future, sperm RNA profiles could become diagnostic tools, helping clinicians assess sperm quality beyond traditional measures like count and motility. They may also guide informed reproductive decisions, especially for couples considering delayed parenthood.

The researchers are now focused on identifying the enzymes and molecular pathways responsible for these RNA changes. If these mechanisms can be understood, they may become targets for interventions aimed at improving sperm quality in aging males.

Extra Context: How Paternal Age Affects Offspring

Large population studies have already linked advanced paternal age to increased risks of autism spectrum disorders, schizophrenia, metabolic conditions, and pregnancy complications. Until now, most explanations centered on DNA mutations or epigenetic changes like DNA methylation.

This study adds sperm RNA as a third major player, suggesting that aging-related risks may arise from a combination of genetic, epigenetic, and RNA-based mechanisms.

Extra Context: What Are Small Non-Coding RNAs?

Small non-coding RNAs, such as tsRNAs and rsRNAs, do not code for proteins. Instead, they regulate gene expression, control protein production, and help guide early embryonic development. Their stability and structure make them especially powerful regulators—small changes can have outsized biological effects.

The discovery that these RNAs change length with age opens an entirely new area of research into male reproductive biology.

Looking Ahead

This study reshapes how scientists think about sperm aging. Instead of a slow decline driven only by DNA damage, sperm appears to carry a time-keeping RNA system that records age at a molecular level.

As research continues, this hidden RNA aging clock may become a key to understanding not only fertility, but how parental age influences health across generations.

Research paper: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44318-025-00687-8