Scientists Finally Explain the Massive Phytoplankton Blooms That Appear Every Summer North of Hawai‘i

Large, swirling phytoplankton blooms have appeared almost like clockwork north of the Hawaiian Islands for years, visible from space as dramatic streaks of green and turquoise across the deep blue Pacific. Despite being easy to spot in satellite imagery, these blooms have long puzzled oceanographers. Where do they come from? Why do they form only at certain times? And what do they mean for ocean ecosystems and Earth’s climate?

A major multidisciplinary study led by researchers at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa has now provided the most complete answers yet. By combining satellite data, ship-based measurements, microbial genetics, nutrient chemistry, and decades of historical ocean records, scientists have pieced together the full biogeochemical anatomy of these enormous blooms. The research was published in the journal Progress in Oceanography and represents the first truly comprehensive investigation of these recurring summer events.

A bloom in the middle of an ocean “desert”

The blooms occur in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, a vast region often described as an ocean desert. Nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus are usually scarce here, which limits biological productivity. For most of the year, the waters north of Hawai‘i support relatively low levels of phytoplankton compared to nutrient-rich coastal regions.

Yet nearly every summer, satellites detect giant phytoplankton blooms, sometimes covering areas comparable in size to entire U.S. states. Previous research had identified one key feature of these blooms: a partnership between diatoms and diazotrophs.

Diatoms are photosynthetic microbes encased in silica-based shells, while diazotrophs are bacteria capable of converting nitrogen gas from the atmosphere into forms that living organisms can use. In nutrient-poor waters, this relationship is extremely valuable, because nitrogen is often the most limiting nutrient. Together, these organisms form what scientists call diatom–diazotroph associations, or DDAs.

What remained unclear was why these blooms suddenly ignite, how they evolve, and what ultimately causes them to collapse.

Catching a rare event at sea

One of the biggest challenges in studying these blooms is their unpredictability. They form quickly, shift location, and do not follow a strict schedule. As a result, most past research relied heavily on satellite observations, with little direct sampling.

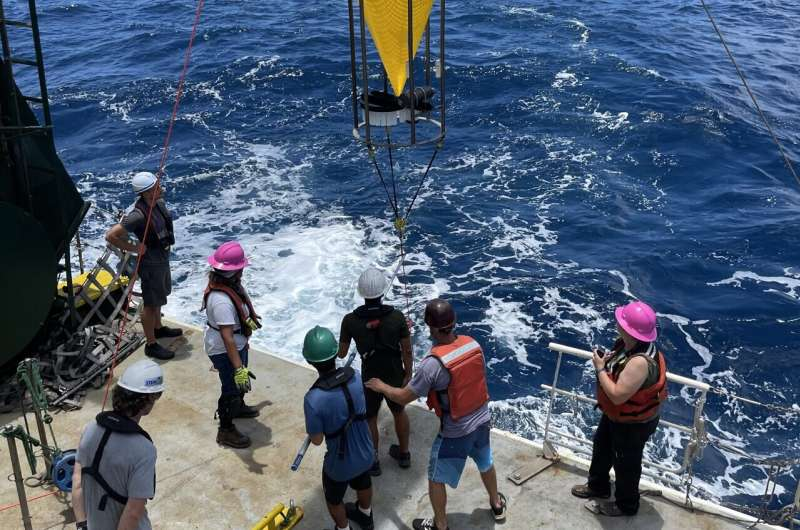

That changed in the summer of 2022, when oceanographers aboard the research vessel R/V Kilo Moana got lucky. While already at sea for a separate expedition focused on organic matter cycling, researchers noticed a massive bloom developing nearby in satellite imagery. The bloom stretched across an area roughly the size of Minnesota, placing it well within reach of the ship.

The team immediately redirected efforts to sample the bloom directly. This rare opportunity allowed scientists to collect water samples, deploy sediment traps, measure photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation rates, analyze microbial DNA, and track nutrient concentrations throughout the water column.

The expedition brought together experts in microbial ecology, ocean chemistry, biological oceanography, and biogeochemistry, making it possible to examine the bloom from multiple scientific perspectives at once.

What actually triggers these blooms?

The study revealed that phytoplankton blooms north of Hawai‘i are not caused by a single factor, but by a specific combination of conditions coming together at the right time.

First, there must already be an elevated seed population of diatom–diazotroph associations present in the water. These organisms are usually there in low numbers, but blooms only happen when their populations are already higher than normal.

Second, the water must contain above-average levels of phosphate and silicate. Phosphate is essential for cellular energy and genetic material, while silicate is critical for building the glass-like shells of diatoms.

Third, the surface mixed layer of the ocean must be unusually shallow. This layer is where wind and waves mix surface waters. When it is shallow, phytoplankton are effectively trapped close to the surface, where sunlight is strongest.

This shallow mixed layer turns out to be especially important for nitrogen fixation, which is an energy-intensive process that works best under bright light conditions. When all of these factors align, phytoplankton growth accelerates rapidly, producing the massive blooms seen from space.

How blooms reshape the upper ocean

As the bloom intensifies, it begins to change the structure of the upper ocean itself. The dense concentration of phytoplankton near the surface absorbs and scatters sunlight, significantly reducing the amount of light that penetrates deeper into the water.

The researchers found that photosynthesis declined sharply below about 50 meters, an unusual pattern for this region. This light reduction altered the normal balance between phytoplankton and bacteria that break down organic matter.

One surprising result was the build-up of ammonium in the lower part of the sunlit zone. Normally, ammonium is quickly recycled by microbes, but the altered light environment disrupted this process, leading to chemical conditions rarely seen in these waters.

In short, the bloom did not just add more life at the surface — it restructured biological and chemical processes throughout the upper ocean.

Using decades of data to understand bloom life cycles

To understand how unusual the 2022 bloom really was, researchers compared their observations with nearly 40 years of data from the Hawai‘i Ocean Time-series (HOT) program. Since 1988, the HOT program has conducted monthly measurements at Station ALOHA, located north of O‘ahu.

This long-term dataset provided a crucial baseline, allowing scientists to distinguish typical background conditions from bloom-driven changes. By comparing the two, the team was able to outline a likely lifecycle for these phytoplankton blooms.

According to the study, blooms likely collapse when one or more key factors shift. Nutrients such as phosphate may become depleted. The mixed layer may deepen, spreading phytoplankton into darker waters. Or mortality may increase as viruses, parasites, and grazers catch up with the rapidly growing microbial populations.

Why these blooms matter for the planet

Beyond their local ecological effects, these blooms have global significance. Diatom–diazotroph associations are relatively heavy organisms. When they die, they sink quickly, carrying carbon with them into the deep ocean.

This process, known as biological carbon export, helps remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it in the ocean interior for long periods. Understanding how often these blooms occur, how large they become, and how efficiently they export carbon is essential for improving climate models.

The study also raises an intriguing question: if nitrogen-fixing organisms can create their own fertilizer, why aren’t they more abundant in these waters year-round? By identifying the environmental limits on diazotroph growth, scientists gain insight into what controls productivity across the world’s vast low-nutrient ocean gyres.

Extra context: phytoplankton and ocean health

Phytoplankton may be microscopic, but they play an outsized role in Earth’s systems. They produce roughly half of the oxygen in the atmosphere and form the base of nearly all marine food webs. Changes in phytoplankton abundance can ripple upward to affect fish populations, carbon cycling, and even climate regulation.

Studies like this one highlight how small shifts in nutrients, light, and ocean physics can trigger dramatic biological responses. As climate change alters ocean temperatures and stratification, understanding these processes becomes even more important.

Research paper:

Foreman, R. K. et al. (2026). Biogeochemical anatomy and ecosystem dynamics of a large phytoplankton bloom north of the Hawaiian Islands. Progress in Oceanography.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2025.103620