Scientists in Denmark Recreate an Ancient Yogurt Recipe Made With Live Ants

A team of scientists in Denmark has brought back a centuries-old Balkan yogurt recipe that uses a rather unexpected ingredient — live red wood ants. The researchers discovered that these ants carry unique bacteria, acids, and enzymes capable of turning ordinary milk into a creamy, tangy yogurt. The study, recently published in iScience, explores how this nearly forgotten practice from the Balkans and Turkey worked, what makes it effective, and how it could inspire modern food innovation.

Rediscovering a Lost Tradition

The idea of using insects in food isn’t new, but this particular tradition was all but forgotten. The research team, led by scientists from the University of Copenhagen and the Technical University of Denmark, traced the origins of this method to rural communities in Bulgaria and Turkey.

In these regions, red wood ants (belonging to the Formica genus) are common forest dwellers. Historically, villagers would use these ants to kickstart milk fermentation — a practice that survived in local memory but had never been scientifically studied in detail.

One of the study’s co-authors, anthropologist Sevgi Mutlu Sirakova, introduced the team to her home village in Bulgaria, where elders still remembered the recipe. Following their guidance, the scientists replicated the exact process step by step.

They warmed fresh milk and added four live red wood ants into a jar. The jar was then covered with cheesecloth and placed inside an ant mound overnight, where the natural warmth and microbial environment helped trigger fermentation.

By the next day, the milk had begun to thicken and sour, forming what the team described as an early stage of yogurt. The texture was soft, and the flavor was tangy, herbaceous, and slightly reminiscent of grass-fed dairy fat.

Understanding How Ants Make Yogurt

To figure out what was happening inside the jar, the team brought samples back to Denmark for detailed analysis. What they found was a remarkable combination of natural chemistry and biology.

The ants themselves, and the microbes living within and on them, provided all the key ingredients for fermentation:

- Lactic and acetic acid bacteria – These beneficial microbes are naturally present in the ants’ digestive systems. They release acids that lower the pH of milk, causing it to thicken and coagulate.

- Formic acid – This acid, which ants produce as part of their defense mechanism, helps acidify the milk and gives the yogurt a distinctive flavor profile.

- Enzymes – Both the ants and their microbial partners release enzymes that break down milk proteins, transforming the milk’s texture and flavor.

This combination creates a holobiont effect — a system where the host organism (the ant) and its microbes work together to carry out fermentation.

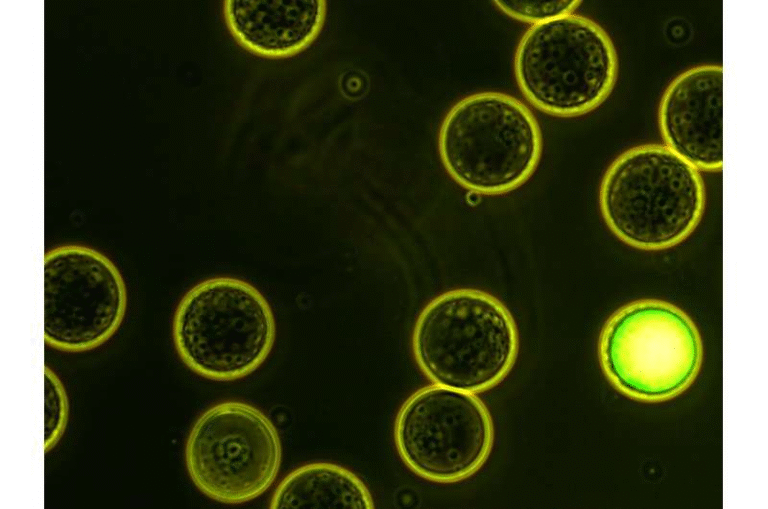

When the researchers compared results, they found that only live ants successfully created the right microbial balance for fermentation. Frozen or dehydrated ants failed to produce the same result. This showed that living microbial ecosystems are necessary to achieve proper fermentation.

The study also found that the yogurt’s bacterial composition included Fructilactobacillus sanfranciscensis, a species commonly found in sourdough bread starters. This connection between ant yogurt and sourdough highlights how similar microbial processes can appear across very different food traditions.

Interestingly, the pH level in the ant yogurt didn’t always reach the standard 4.6 (typical of commercial yogurts). Yet, the milk still thickened — suggesting that the combination of acids and enzymes worked differently from conventional yogurt cultures.

From Ancient Tradition to Modern Cuisine

Once the scientific process was clear, the team wondered whether this discovery could inspire modern gastronomy. They partnered with Alchemist, a two-Michelin-star restaurant in Copenhagen known for pushing culinary boundaries.

At Alchemist, chefs experimented with the fermented ant yogurt to create several creative dishes:

- A yogurt ice cream sandwich shaped like an ant.

- A mascarpone-like cheese made with ant yogurt, noted for its rich and pungent tang.

- A cocktail clarified using a milk wash made from the ant-fermented yogurt instead of citrus.

The chefs described the acidity from the ants as lemony but more complex, adding a new layer of flavor to drinks and desserts.

These experiments show that even the strangest traditional foods can find a place in modern fine dining when reinterpreted through science and creativity.

Safety and Sustainability Concerns

While the results are fascinating, the researchers caution that this process should not be attempted at home. Live ants can carry parasites and harmful bacteria, making the yogurt unsafe if handled incorrectly.

When they tried using frozen or dried ants, not only did the fermentation fail, but unwanted bacteria were able to grow — reinforcing that the process requires careful microbial control.

There’s also an ecological concern. Red wood ants are important forest species and are considered vulnerable in some European regions. Using them widely for food production could disrupt local ecosystems. The researchers emphasize that their work was meant for scientific understanding and culinary experimentation, not mass production.

What Makes This Discovery Important

This study isn’t just about a quirky recipe — it highlights the biocultural heritage of food. Traditional fermentation methods often rely on naturally occurring microbes in the environment, leading to complex flavors and unique local products.

Modern commercial yogurts, by contrast, usually use just two bacterial strains, offering consistency but little microbial diversity. Rediscovering older methods like ant yogurt could help expand the microbial palette of future food innovations.

This discovery also contributes to a broader field called hologenomics, which studies how hosts and their microbiomes work together. In this case, the ant’s own biology and its associated microbes jointly drive fermentation — a perfect example of how nature’s tiny ecosystems can have practical uses.

For the scientists, the project was also a reminder that ancient food traditions, even those that seem strange today, often contain deep microbial knowledge passed down through generations. They argue that listening to these old methods can inspire new approaches to sustainable and creative food design.

A Closer Look: The Microbes Behind Fermentation

To appreciate how this works, it helps to understand the microbes involved.

- Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB): These are the same types found in yogurt, sauerkraut, kimchi, and sourdough. They ferment sugars (like lactose) into lactic acid, which preserves and thickens food.

- Acetic Acid Bacteria: Common in vinegar production, these microbes produce acetic acid from sugars and alcohols. In ant yogurt, they contribute to the tangy, slightly sharp flavor.

- Fructilactobacillus sanfranciscensis: Known from sourdough fermentation, this bacterium adds mild sourness and depth of flavor. Its presence in the ant yogurt suggests overlapping microbial networks between dairy and bread fermentations.

- Formic Acid: Produced naturally by ants, this acid not only affects flavor but also acts as an antimicrobial agent, helping to keep harmful bacteria at bay.

Together, these elements form a natural fermentation system that doesn’t need any commercial starter culture. It’s a self-contained microbial engine powered by the ant and its symbiotic community.

How Does It Compare to Regular Yogurt?

Modern yogurts typically rely on two bacterial species — Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus. These strains are predictable and safe, but they produce limited flavor variation.

In contrast, traditional yogurts (and now ant yogurt) involve a wider microbial diversity, which creates more complex flavors, textures, and aromas. The downside is that they’re harder to control and less consistent from batch to batch.

Ant yogurt, with its natural acids and enzymes, forms a different texture — sometimes softer or more custard-like, with a rich aroma. It’s not identical to store-bought yogurt but has its own distinct appeal.

The Future of Ant-Based Fermentation

While it’s unlikely that you’ll see jars of “ant yogurt” on supermarket shelves anytime soon, the implications are exciting. Understanding how insects contribute to fermentation could lead to new sustainable food processes that use insect-derived microbes or enzymes without requiring live insects.

Insects are already being explored as protein sources, but this study adds another dimension — using their natural chemistry for food transformation. In the future, researchers may isolate the beneficial bacteria and enzymes from ants and apply them in controlled food manufacturing environments.

This could open up new avenues for low-energy fermentation, novel plant-based dairy alternatives, or flavor development in high-end cuisine.

A Reminder of What Tradition Can Teach Science

In a world dominated by industrial food production, discoveries like this remind us that ancient knowledge still matters. The villagers who once dropped ants into milk weren’t microbiologists, but they understood through experience how nature could transform food.

By combining that traditional wisdom with modern science, researchers are uncovering new insights into how tiny ecosystems like an ant’s microbiome can shape flavor, nutrition, and creativity in the kitchen.

As one of the researchers noted, the goal isn’t to popularize eating ants, but to appreciate the science hidden inside old recipes — and perhaps to listen more closely when someone’s grandmother shares a story about an unusual dish.