Scientists Map the First High-Resolution Structure of a Key Herpes Virus Protein, Opening Doors to Next-Generation Antivirals

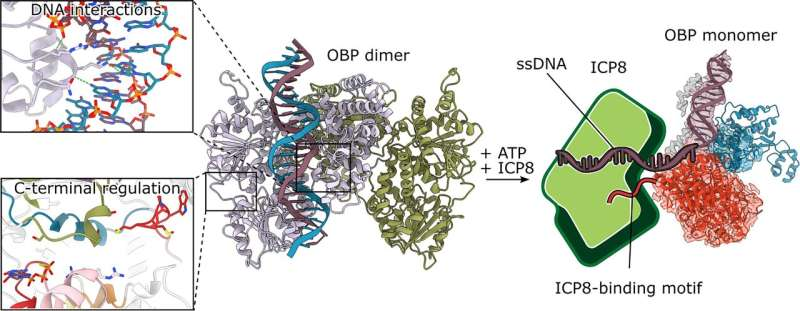

For the first time, researchers have captured an incredibly detailed, high-resolution view of a key protein used by the herpes simplex virus (HSV-1) to start replicating its DNA. This breakthrough, achieved through cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), finally reveals the architecture and mechanisms of the long-mysterious origin-binding protein (OBP) — a molecule that’s been studied for four decades but never seen this clearly.

The work, published in Nucleic Acids Research (2025), was led by an international team from Karolinska Institutet, the University of Gothenburg, and the Center for Structural Systems Biology (CSSB) in Hamburg. The researchers achieved resolutions as fine as 2.8 angstroms, providing an unprecedented molecular blueprint for how herpes viruses begin to copy their genetic material — and where future antiviral drugs could strike.

Understanding the Target: What Is OBP and Why It Matters

The herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) infects roughly 70 percent of the global population. While it’s best known for causing cold sores, in severe cases it can lead to herpes encephalitis, a potentially fatal inflammation of the brain. The virus can also reactivate after lying dormant in nerve cells, particularly in immunocompromised patients such as those undergoing chemotherapy or bone-marrow transplants.

Current HSV-1 treatments almost exclusively block the viral DNA polymerase, the enzyme that copies the viral genome once replication has already begun. However, because this target has been used for decades, drug resistance is rising, and many patients with weakened immune systems now struggle with infections that no longer respond to standard antivirals.

That’s where OBP (Origin-Binding Protein) comes in. This viral protein is the very first player in the replication process — it identifies specific sequences in the viral genome called origins of replication (OriS) and begins to unwind the DNA, paving the way for other viral enzymes to follow.

Until now, no one had been able to capture OBP’s full structure. Despite decades of biochemical studies, researchers only had indirect models based on partial data. The new high-resolution cryo-EM structures finally reveal what OBP looks like in action — and how it performs its job.

How the Study Was Done

Using state-of-the-art cryo-electron microscopy, the scientists reconstructed OBP in multiple functional states:

- Bound to viral DNA origin sequences, showing how it recognizes and grips the viral genome.

- Complexed with an ATP analog, simulating the energy-driven stage of DNA unwinding.

- In dimeric and multimeric forms, representing how the protein pairs and assembles during replication.

By freezing OBP in these different configurations and imaging it at cryogenic temperatures, the team achieved atomic-level detail, allowing them to map the positions of key amino acids, the folds of the protein domains, and the way it interacts with both DNA and ATP.

Surprising Structural Discoveries

One of the biggest surprises was how OBP molecules interact. Instead of forming the symmetrical dimer scientists expected, OBP assembles in a head-to-tail dimer, meaning one molecule’s end loops into its partner in a unique intertwined fashion.

At the very end of the protein chain lies the C-terminal region, which unexpectedly threads through the partner molecule and positions itself right next to the ATP-binding pocket — the site responsible for energy handling. This was the first clue to an internal regulatory mechanism.

Deleting this C-terminal tail, past research showed, makes OBP spin its helicase motor faster but paradoxically makes replication less efficient. The new structure explains why: this tail acts as a built-in brake that prevents the helicase from running wild. When another viral protein called ICP8 — a single-stranded DNA-binding protein — attaches to OBP, it likely releases this brake, switching OBP from a recognition mode to an active unwinding mode.

In essence, the OBP structure provides a mechanical explanation for how HSV-1 precisely controls the start of replication.

New Drug Targets Revealed

The detailed OBP structures uncovered several promising points for antiviral drug design:

- The DNA-Binding Motif – A unique site responsible for recognizing the origin of replication. Disabling this feature could prevent the virus from even finding where to start copying its DNA.

- The Dimer Interface – The area where two OBP molecules lock together. Targeting this interface could destabilize the complex and halt replication at its earliest stage.

- The ICP8-Binding Region – Since ICP8 releases the internal brake, blocking this interaction might lock the protein in an inactive state.

- The ATP-Binding Pocket – OBP’s ATP site is structurally different from that of human helicases, offering a potential selective target for antiviral compounds that won’t harm host cells.

With these findings, the researchers have essentially provided a molecular roadmap for the next generation of herpes drugs — therapies that could not only combat resistant strains but also reduce viral reactivation from latency.

Why This Discovery Is Urgently Needed

Herpesviruses pose a persistent clinical challenge, especially for people with weakened immune systems. In cancer patients, herpes reactivation during treatment is a common and dangerous complication. When resistance develops, clinicians often have to turn to older, more toxic drugs like foscarnet, which can damage kidneys and are far less effective.

By targeting OBP, scientists hope to interrupt the infection earlier — before the virus even begins to copy its DNA — and to avoid resistance pathways associated with the polymerase.

Beyond treatment, there’s also growing interest in the potential connection between latent herpesvirus infections and neurodegenerative diseases. Some studies suggest HSV-1 may contribute to Alzheimer’s-like pathology under certain conditions. If researchers can design drugs that keep the virus permanently dormant, it could open up entirely new therapeutic possibilities beyond traditional antiviral use.

A Step Forward in Viral Structural Biology

Solving this structure isn’t just a win for herpes research — it’s also a milestone for structural virology in general. The fact that a protein as elusive as OBP could finally be resolved at near-atomic precision shows how far cryo-EM technology has come.

By reaching resolutions as fine as 2.8 Å, the researchers could visualize tiny structural motifs, such as the RVKNL sequence, that define OBP’s sequence-specific DNA recognition. The data sets — including cryo-EM maps and atomic coordinates — have been publicly deposited in the Protein Data Bank and related archives, meaning other scientists can now build on this work immediately.

Looking Ahead

This study doesn’t mean we already have a new drug, but it gives scientists the blueprint to start designing one. The next steps involve screening small molecules that can bind to these newly discovered pockets and testing whether they can block HSV replication in cells.

Because herpesviruses share a lot of similarities, this discovery could also inspire cross-virus research. Proteins analogous to OBP exist in HSV-2 (which causes genital herpes) and varicella-zoster virus (which causes chickenpox and shingles). Understanding HSV-1 OBP may help in developing drugs effective against multiple members of the herpes family.

Finally, by studying how OBP transitions between its inactive (recognition) and active (unwinding) states, scientists may uncover more about how herpesviruses establish latency in the first place — one of the biggest mysteries in virology.

The Bigger Picture

What makes this discovery truly exciting is its timing. As global research turns toward tackling persistent viral infections and preventing reactivations, having precise molecular targets is invaluable. For herpes, where no vaccine yet exists, structure-based drug design could finally offer long-term control instead of lifelong suppression.

The OBP findings are a reminder that even long-studied viruses still hold secrets — and that cryo-EM has become one of the most powerful tools for revealing them. With continued collaboration between structural biologists, virologists, and medicinal chemists, we might soon see the first antivirals aimed at the very start of herpes replication, not just the aftermath.

Research Reference: The herpes simplex origin-binding protein: mechanisms for sequence-specific DNA binding and dimerization revealed by Cryo-EM (Nucleic Acids Research, 2025)