Scientists Reveal the Near-Atomic Structure of Cholera’s Flagellar Tail and Why It Matters for Treatment

Cholera remains one of the world’s most dangerous bacterial diseases, claiming an estimated 95,000 lives every year. It is caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, which infects the small intestine and triggers severe diarrhea and dehydration. While public health efforts have reduced outbreaks in many regions, cholera is still a major threat in areas with limited access to clean water and sanitation. A new study has now shed light on one of the bacterium’s most important tools for infection: its flagellum, a powerful tail-like structure that allows it to move rapidly through liquid environments.

Researchers from Yale School of Medicine, led by microbiologist Jun Liu, have used advanced imaging techniques to uncover the molecular structure of the cholera flagellum in unprecedented detail. Their findings, published in Nature Microbiology, solve a mystery that has puzzled scientists for nearly 70 years and could open the door to new treatment strategies that target bacterial movement rather than traditional pathways like toxin production.

Why the Cholera Flagellum Is So Important

The flagellum is essentially a microscopic propeller. In Vibrio cholerae, it appears as a single thin tail protruding from one end of the bacterium. This structure allows the bacteria to swim at remarkable speeds, especially in watery environments like rivers, estuaries, and the human gut.

This speed is not just a neat biological trick. Scientists believe it plays a key role in infection. When V. cholerae enters the human body, it must push through the thick mucus layer that protects the lining of the small intestine. Strong, fast movement helps the bacteria penetrate this barrier and attach to intestinal cells, where they can multiply and release toxins.

Because of this, bacterial motility has long been recognized as a virulence factor. In fact, some cholera vaccines work partly by reducing the bacterium’s ability to move, making it less effective at causing disease.

A Longstanding Scientific Puzzle

Scientists have known about cholera’s unusual flagellum since the 1950s. Over decades of research, they identified the four different proteins, called flagellins, that make up the flagellar filament. However, knowing the components is not the same as understanding how they fit together.

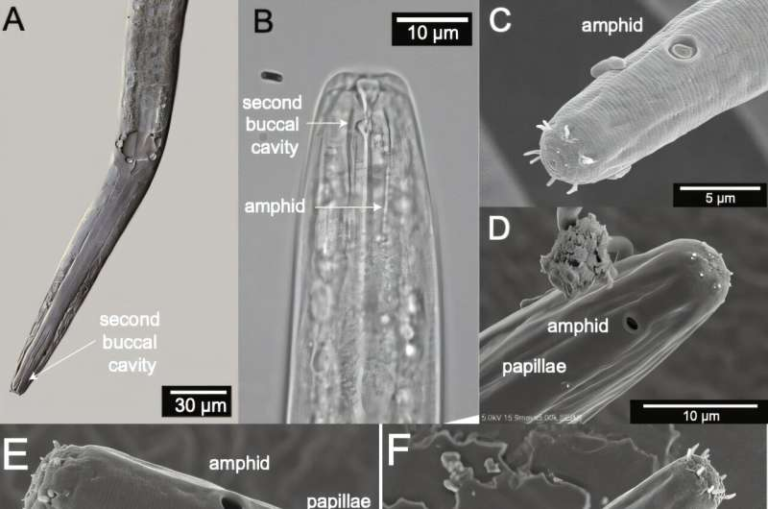

The biggest challenge has been the flagellum’s sheath. Unlike many bacteria, V. cholerae has a flagellum that is surrounded by a hydrophilic (water-loving) casing derived from the bacterium’s outer membrane. This sheath hides the internal structure and makes it extremely difficult to study using conventional microscopy.

On top of that, most high-resolution molecular techniques require scientists to kill the bacteria and isolate individual proteins. That approach strips away the natural context, making it impossible to see how the parts are arranged in a living cell. As a result, the true structure of the cholera flagellum remained unknown for decades.

Seeing the Flagellum in Living Bacteria

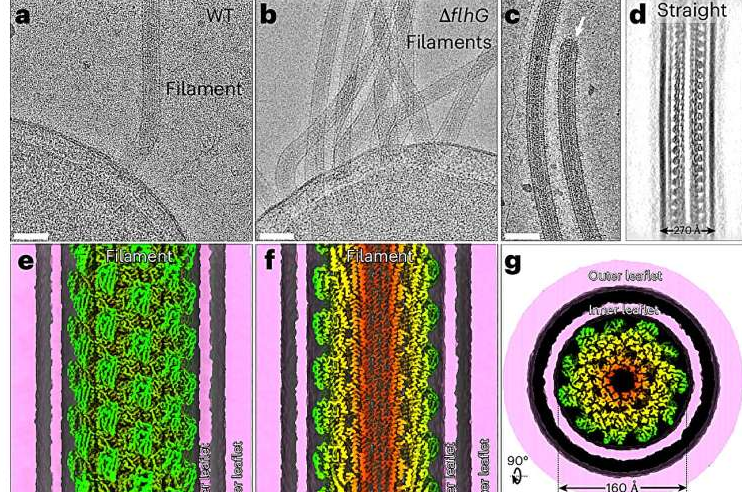

To overcome these obstacles, the Yale research team turned to in situ cryo–electron microscopy, a powerful technique that allows scientists to image biological structures at near-atomic resolution while preserving their natural state.

The researchers genetically engineered V. cholerae so that its flagellar proteins could be visually distinguished under the microscope. The bacteria were then rapidly frozen in liquid ethane, a step that locks all cellular components in place without damaging them. Using an advanced electron microscope, the team was able to visualize the flagellum inside intact, living bacteria.

This approach provided a detailed view that had never been possible before. According to the researchers, achieving this level of resolution was essential for understanding how the flagellum is assembled and how it functions during movement.

Four Flagellins, Four Distinct Zones

One of the most striking discoveries was how the four flagellin proteins are arranged. Rather than being mixed randomly, each protein occupies a specific zone along the length of the flagellar filament.

The study revealed that:

- Different flagellins are localized to distinct regions, from the base of the flagellum to its tip.

- This spatial organization gives the flagellum a consistent core structure, similar to flagella in other bacteria.

- At the same time, the outer surface is unique, reflecting adaptations linked to the surrounding sheath.

This precise arrangement helps explain how V. cholerae builds such a robust and efficient motility system. It also suggests that the bacterium has evolved specialized features that set its flagellum apart from those of other microbes.

How the Sheath May Boost Speed

The study also offers new clues about why cholera bacteria move so fast. One possibility lies in the relationship between the filament and its sheath.

The images suggest that the flagellar core rotates independently from the outer sheath. Because the sheath is hydrophilic, it may act like a lubricated sleeve, reducing friction as the filament spins. This setup could allow the bacterium to move more smoothly and efficiently through liquid environments, including the mucus-rich surroundings of the human intestine.

While this idea needs further testing, it provides a compelling explanation for cholera’s exceptional motility and highlights how subtle structural differences can have major biological effects.

Implications for Cholera Treatment

Understanding the detailed structure of the cholera flagellum is more than an academic achievement. It has practical implications for fighting the disease.

Most current cholera treatments focus on managing symptoms, especially dehydration, or killing the bacteria with antibiotics. However, targeting bacterial movement offers a different strategy. If drugs could interfere with flagellum assembly, rotation, or sheath function, they might reduce the bacterium’s ability to infect, even if it remains alive.

The high-resolution images produced in this study provide a blueprint for such efforts. Researchers can now pinpoint specific structural features that might serve as drug targets, potentially leading to new therapies that complement existing treatments.

Extra Context: Flagella and Bacterial Life

Flagella are not unique to Vibrio cholerae. Many bacteria use these structures for movement, navigation, and environmental sensing. However, cholera’s flagellum stands out because it is:

- Single and polar, rather than multiple and distributed.

- Sheathed, unlike the exposed flagella of many other bacteria.

- Powered by sodium ions instead of protons, which may contribute to higher torque and speed.

Beyond motility, flagella also influence biofilm formation, chemotaxis, and interactions with host immune systems. This makes them central to bacterial survival both in the environment and inside hosts.

Looking Ahead

The researchers emphasize that this work is just the beginning. Now that the structure of the cholera flagellum has been revealed at near-atomic resolution, scientists can begin exploring how it assembles, how it rotates, and how it responds to different conditions.

More broadly, the imaging techniques developed for this study could be applied to other bacteria with complex or hidden structures, opening new windows into microbial life.

By finally solving a decades-old mystery, this research brings us closer to understanding how Vibrio cholerae moves, infects, and survives—and how we might one day stop it more effectively.

Research paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41564-025-02161-x