Scientists Uncover a Hidden Winter Memory Inside Plants

Scientists have long known that many plants need to experience winter before they can flower in spring. What has remained a mystery is how plants actually remember winter at the cellular level. Now, a new study has finally provided direct visual evidence of this process, thanks to a powerful microscopy technique that allows researchers to see deep inside living plant tissues for the first time.

Researchers from the University of York have developed a new imaging method that reveals how plants store a molecular “memory” of cold conditions. This discovery not only answers a decades-old biological question but also opens new possibilities for understanding how plants adapt to seasonal changes, environmental stress, and climate shifts.

Why Plants Need to Remember Winter

Many plants from temperate regions rely on a process known as vernalization. This is a biological requirement where plants must experience a prolonged period of cold before they are capable of flowering. Without winter, these plants stay locked in a non-flowering state, even when spring conditions arrive.

This mechanism ensures that plants do not flower too early, which could be disastrous if frost returns. Instead, flowering is delayed until winter has clearly passed. Scientists have known for years that this process involves epigenetic changes, meaning changes that affect how genes behave without altering the DNA sequence itself. However, seeing how these changes form and persist inside living plant cells has been nearly impossible—until now.

The Challenge of Seeing Inside Plant Cells

Plant tissues are thick, dense, and highly complex. Traditional microscopes struggle to see more than a few micrometers into living tissue before light becomes scattered and images turn blurry. The proteins responsible for winter memory are located deep inside plant cell nuclei, buried under multiple layers of tissue.

Because of this limitation, much of what scientists understood about vernalization came from indirect evidence rather than direct observation. Researchers knew which genes were involved, but not how the molecular machinery physically organized itself during cold exposure.

Introducing SlimVar: A New Way to See Deep Inside Plants

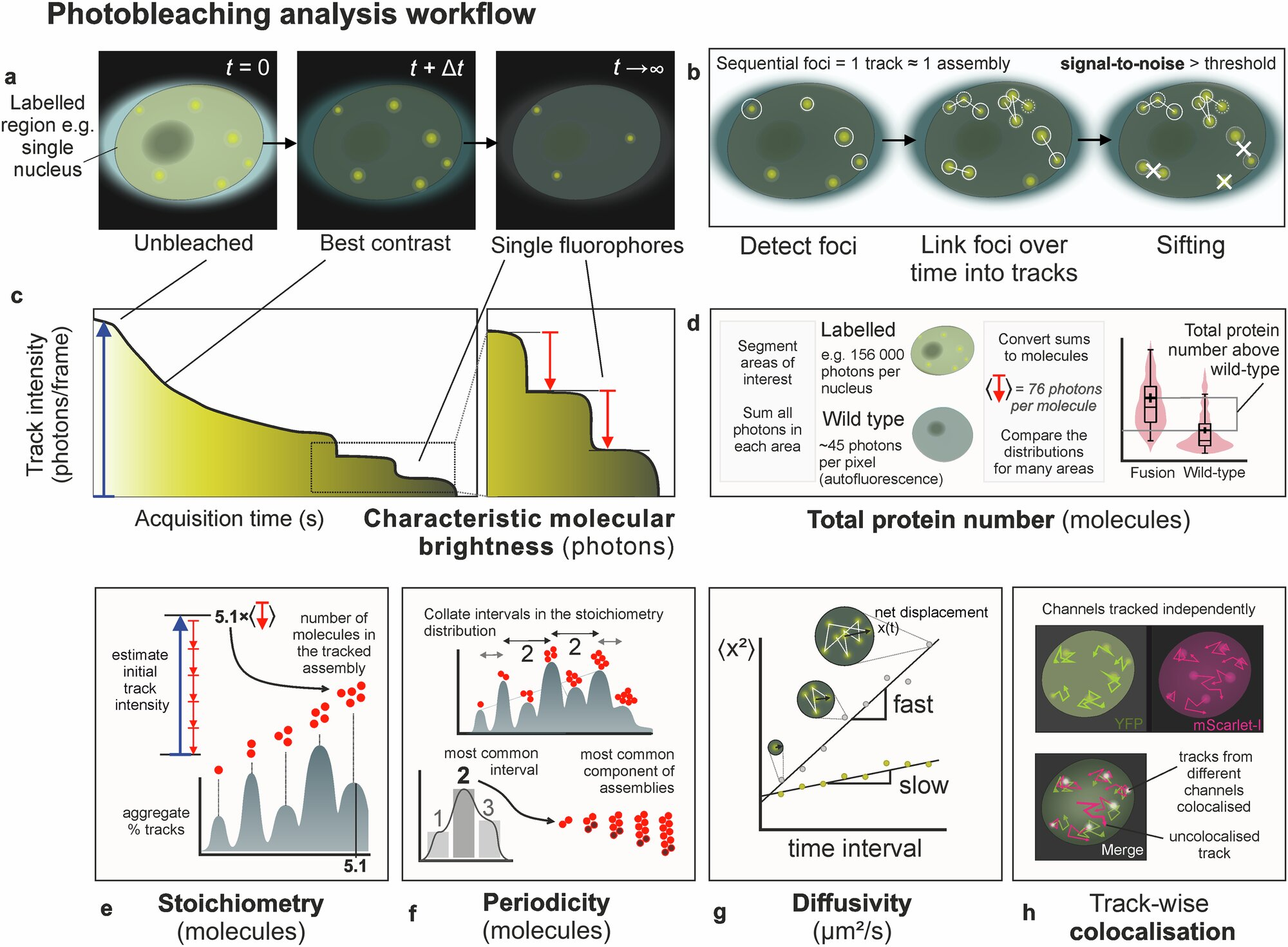

To overcome this challenge, the University of York team developed a technique called SlimVar, short for Variable-angle Slimfield microscopy. This method acts like an ultra-sensitive camera for the microscopic world.

SlimVar works by carefully adjusting the angle of incoming light and combining it with advanced computational processing. This allows researchers to cut through the optical “noise” that normally limits deep-tissue imaging. Using this approach, scientists can track individual molecules in real time at depths of up to 30 micrometers inside living plant roots—far deeper than traditional methods allow.

Most importantly, SlimVar can follow single protein molecules as they move, cluster, and interact, offering a direct view of molecular behavior inside living cells.

Key Proteins That Control Flowering

Using SlimVar, the researchers focused on two proteins known to play a central role in vernalization: VIN3 and VRN5. These proteins are involved in switching off a gene that prevents flowering. When this gene remains active, the plant cannot flower, no matter how favorable the conditions are.

During exposure to cold temperatures, VIN3 and VRN5 begin to assemble into tiny clusters inside the nucleus of plant cells. These clusters were previously impossible to observe directly in living tissue.

The researchers discovered that during cold conditions, these protein clusters more than doubled in size. Some of them formed around a gene associated with flowering repression, while others appeared nearby within the nucleus.

How Plants Store a Memory of Winter

One of the most important findings of the study was that many of these protein clusters remained intact even after the plant was warmed again. This persistence is what allows the plant to remember that winter has already occurred.

These long-lasting clusters act as molecular memory hubs, maintaining the silencing of the flowering-blocking gene. As a result, once spring arrives, the plant no longer needs to re-experience cold conditions—it already “knows” winter is over and can safely begin flowering.

This discovery provides the clearest evidence yet that epigenetic memory in plants is tied to physical protein assemblies, not just abstract chemical marks on DNA.

What This Means for Epigenetics

Epigenetics refers to biological changes that affect gene activity without altering the genetic code itself. In plants, epigenetic regulation allows organisms to respond flexibly to environmental cues like temperature, light, and stress.

The findings from this study show that epigenetic memory is not just a static chemical modification. Instead, it involves dynamic protein structures that can form, grow, and persist over time. This adds an entirely new layer to how scientists understand gene regulation in living organisms.

Why This Discovery Matters Beyond Flowering

The implications of this research extend far beyond flowering plants. Being able to observe molecular behavior deep inside living tissues opens new possibilities across plant science.

SlimVar could be used to study how plants respond to drought, heat stress, disease, and soil conditions. It may also help scientists understand how crops adapt—or fail to adapt—to rapidly changing climates.

In agriculture, this knowledge could eventually support the development of crops that are better tuned to unpredictable winters or shifting seasonal patterns, helping improve food security in a warming world.

A Major Step Forward for Plant Biology

Until now, studying epigenetic processes inside thick plant tissues was largely theoretical or relied on indirect measurements. SlimVar changes that by allowing scientists to watch these processes unfold in real time.

This research represents a major technical and conceptual breakthrough, offering a direct window into how plants integrate environmental history into long-term biological decisions.

Research Reference

Payne-Dwyer, A. L. et al. “SlimVar for rapid in vivo single-molecule tracking of chromatin regulators in plants.” Nature Communications (2025).

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-63108-8