Spray-On Antibacterial Coating Could Help Plants Fight Disease and Survive Drought

Engineers at the University of California San Diego have developed a spray-on polymer coating that could give plants an extra layer of protection against bacterial diseases while also helping them cope better with drought conditions. The research, published in ACS Materials Letters, explores a new materials-based approach to plant health at a time when agriculture is under growing pressure from climate change, rising temperatures, and increasingly aggressive plant pathogens.

Bacterial infections are a serious and expanding threat to global agriculture. They are responsible for large crop losses every year and cause destructive plant diseases such as wilt, blight, speck, and canker. Both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria play a role in these infections, and warming climates are allowing many pathogens to spread into regions where they were not previously found. This combination of factors means crops are now exposed to a broader and more intense range of disease pressures than ever before.

To address this challenge, researchers from the laboratories of Jon Pokorski and Nicole Steinmetz, professors in the Aiiso Yufeng Li Family Department of Chemical and Nano Engineering at UC San Diego, collaborated to design a coating that can be sprayed directly onto plant leaves. Both labs are also part of the university’s Materials Research Science and Engineering Center (MRSEC), which focuses on advanced materials development.

The result is a synthetic polymer-based coating with built-in antibacterial properties. The polymer contains positively charged chemical groups that interact with bacterial cell membranes. Because bacterial membranes are generally negatively charged, these interactions disrupt the membrane structure, leading to bacterial death. This mechanism makes the coating effective against a wide range of harmful bacteria rather than targeting just one specific pathogen.

One of the most important aspects of this work is how the polymer is made. Traditional polymer synthesis often relies on organic solvents, many of which are toxic to plants. The UC San Diego team modified a common polymer synthesis technique so it could be carried out in gentle, water-based buffer conditions. This adjustment allowed them to produce a polymer that is far more plant-friendly and suitable for direct application on leaves.

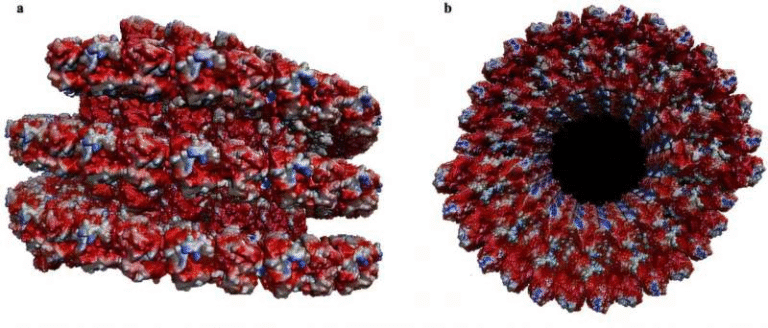

Using this approach, the researchers created a polymer known as polynorbornene. This material has an additional advantage: it is permeable to gases. Gas permeability is critical because plant leaves need to exchange gases such as oxygen and carbon dioxide in order to photosynthesize and grow. A coating that blocked this exchange would harm the plant, but polynorbornene allows normal leaf function to continue.

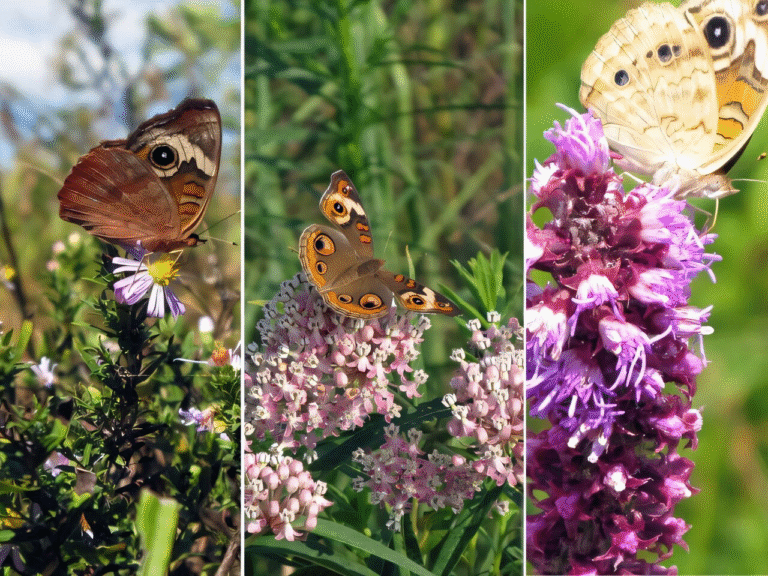

The coating was tested on Nicotiana benthamiana, a plant species widely used in laboratory studies and in plant molecular farming, where plants are used to produce high-value molecules. When sprayed onto living plants, the coating successfully protected them against Agrobacterium infection, a common plant pathogen. In additional tests using individual leaves placed in petri dishes, the coating inhibited the growth of both Gram-negative bacteria like Escherichia coli and Gram-positive bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus.

One of the more surprising findings from the study was that full leaf coverage was not required for protection. Even when researchers sprayed only a small portion of a leaf, the entire plant showed increased resistance to bacterial infection. This unexpected result suggests that the coating does more than just act as a physical antibacterial barrier on the leaf surface.

The researchers believe this whole-plant protection may be linked to a systemic stress response. After treatment, the sprayed leaves briefly showed a mild increase in hydrogen peroxide, a molecule plants naturally produce as part of their stress and defense signaling systems. Over time, hydrogen peroxide levels returned to normal, and the plants remained healthy. The team hypothesizes that this temporary stress signal may activate broader immune defenses throughout the plant, effectively priming it to resist bacterial attack.

In addition to disease resistance, the coating also appeared to improve drought tolerance. In experiments where water was withheld for four days, treated plants stayed healthier and showed less wilting than untreated plants. The researchers suggest two possible explanations for this effect. First, the polymer coating may act as a physical barrier that reduces water loss from the leaf surface. Second, the same stress-related signaling pathways that enhance bacterial resistance may also trigger molecular responses that help plants cope with limited water availability.

While these results are promising, the researchers emphasize that this work represents an early step toward practical agricultural use. Ongoing studies will focus on understanding the exact mechanisms behind the whole-plant immune response and drought resistance. The team is also working to improve the biodegradability of the polymer and to carefully evaluate its toxicity and environmental impact, both of which are essential considerations before any field deployment.

The long-term goal is to develop a technology that can be safely used in real-world farming to protect crops and improve resilience. As environmental stresses intensify and global food demands continue to rise, approaches like this one could play an important role in strengthening food security.

Understanding Antibacterial Polymers in Agriculture

Antibacterial polymers have been widely studied in medical and industrial settings, but their application in agriculture is relatively new. These materials are designed to kill or inhibit microbes through physical and chemical interactions, rather than relying on traditional antibiotics or pesticides. This approach can reduce the risk of resistance development, a growing concern in both human health and agriculture.

In plant systems, antibacterial coatings offer an alternative to chemical sprays that may harm beneficial microbes or accumulate in soil and water. A spray-on polymer that is effective, biodegradable, and safe for plants could complement existing disease management strategies rather than replace them entirely.

Why Gas Permeability Matters for Plant Coatings

One of the key technical challenges in developing leaf coatings is maintaining gas exchange. Leaves constantly take in carbon dioxide for photosynthesis and release oxygen and water vapor. Any coating that interferes with this process can stunt growth or damage the plant. The use of a gas-permeable polymer like polynorbornene is therefore a critical design choice and a major reason this coating shows promise.

The Bigger Picture for Climate-Resilient Crops

Climate change is increasing both disease pressure and water stress on crops worldwide. Solutions that address multiple stressors at once, such as this spray-on coating, are especially valuable. While more testing is needed, the ability to enhance both bacterial resistance and drought tolerance using a single, simple application highlights the potential of materials science to contribute to sustainable agriculture.

Research Paper Reference

https://doi.org/10.1021/acsmaterialslett.5c00798