Stanford Scientists Warn That The Most Unusual Sharks Are Disappearing, Leaving Only Average Species Behind

Sharks, the ocean’s oldest predators, have survived for over 400 million years, evolving into hundreds of unique forms that range from the tiny dwarf lanternshark, small enough to fit in your palm, to the massive whale shark, the size of a school bus. But a new study led by Stanford University researchers warns that this incredible variety could soon shrink dramatically. If current extinction trends continue, the world’s shark populations will become far more homogeneous, losing the rare and extraordinary species that give these creatures their remarkable diversity.

The study, published in Science Advances, reveals that the most distinctive sharks—those with unusual body shapes, diets, and ecological roles—are the ones most likely to go extinct. This means future oceans may be dominated by only medium-sized, generalist sharks living in mid-depth waters, while more specialized species disappear. The researchers describe this as “phenotypic homogenization”, a scientific term for when species become more alike in their physical and ecological traits.

What the Study Found

The Stanford team focused on a shark genus called Carcharhinus, which includes some of the most recognizable sharks such as the bull shark, blacktip shark, and oceanic whitetip shark. These species play vital roles in maintaining marine ecosystems by regulating prey populations and keeping ocean food webs balanced.

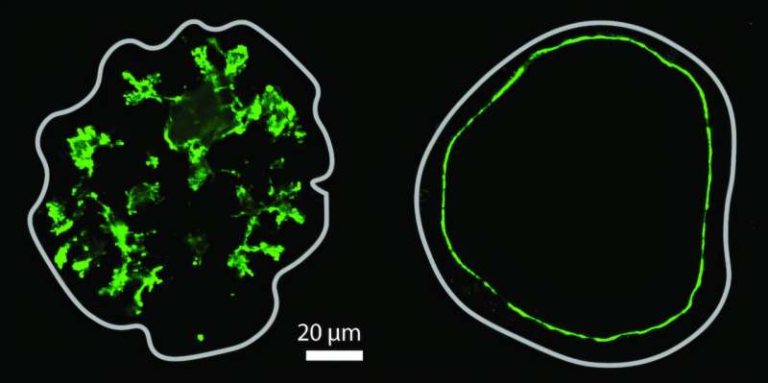

According to data from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), of the 35 recognized species of Carcharhinus, 25 are currently listed as Vulnerable, Endangered, or Critically Endangered. To understand which sharks are most at risk, the researchers analyzed more than 1,200 shark teeth from 30 species within this genus.

Shark teeth serve as a reliable clue to their overall size, diet, and hunting style. Larger teeth typically indicate a larger body size, while the shape and serration patterns of the teeth reveal whether a shark eats fish, squid, or larger prey. By studying tooth shapes and combining that data with extinction risk information, the scientists found a consistent pattern: the more unusual or specialized a shark’s form and ecology, the higher its extinction risk.

Species that were closer to the average—those around 3 to 15 feet long, living in mid-ocean regions, and capable of eating a variety of prey—were far less threatened. On the other hand, sharks adapted to specific depths or with specialized diets, such as surface-dwellers or deep-sea species, faced much greater danger.

Why These Results Matter

This discovery is worrying because sharks are not just one type of animal doing the same job in the ocean. Each species has a unique role. Some keep coral reefs healthy by controlling fish populations, others recycle nutrients by scavenging, and large apex predators maintain the balance of entire ecosystems. Losing unique sharks doesn’t just reduce biodiversity—it disrupts the functionality of marine ecosystems.

The researchers warn that if these distinctive species vanish, what remains will be a far more uniform group of sharks. The oceans could end up dominated by a handful of “average” species, while the rare and unusual ones disappear forever. Such a loss would be a huge blow to marine ecosystems, as well as to human understanding of evolution.

Sharks have been a source of inspiration for biomimicry—a scientific field that draws design ideas from nature. Their skin structure has inspired materials that reduce drag in water, and their streamlined bodies have influenced aerospace and submarine designs. Losing the unique traits of specialized sharks means losing millions of years of evolutionary innovation and potential discoveries.

The Main Threat: Overfishing

While habitat loss, pollution, and climate change all contribute to shark population declines, the biggest driver of shark extinction is overfishing. Sharks are caught for their meat, fins, and liver oil, and many die as accidental bycatch in large-scale commercial fishing operations. The problem is intensified by the fact that sharks reproduce slowly—many species take years to mature and produce only a few offspring at a time.

The researchers highlight that without immediate intervention, the pace of shark loss could accelerate. However, they also point out that recovery is possible when effective conservation measures are implemented.

They cite the example of the northern elephant seal, once nearly exterminated for its blubber, which was used to make lamp oil. In the late 1800s, the population dwindled to just a few dozen individuals off Baja California. But after the United States and Mexico banned hunting, elephant seals rebounded spectacularly—today, there are over 150,000 seals living along the Pacific coast.

The lesson, according to the Stanford scientists, is clear: if strong conservation efforts can work for elephant seals, they can work for sharks too.

How Trait Diversity Keeps Oceans Healthy

Most people think of conservation in terms of saving species, but this study emphasizes something deeper—trait diversity. This refers to the range of physical and ecological differences among species. In sharks, trait diversity includes variations in size, feeding behavior, hunting depth, and body form.

When ecosystems lose trait diversity, they become less resilient to environmental changes. In simple terms, a system made up of similar species can collapse more easily if a disturbance affects them all in the same way. On the other hand, a diverse set of species with different traits provides stability and adaptability.

For example, if mid-depth generalist sharks dominate while deep-sea and surface species disappear, entire ecosystems could lose functions like nutrient cycling and prey regulation in those zones. The ocean would still have sharks—but it would lose the balance that makes marine life thrive.

What Can Be Done

The study’s message isn’t one of despair—it’s a call to action. The researchers emphasize that conservation can still turn the tide. Protecting shark diversity requires better enforcement of fishing regulations, stronger bans on shark finning, the establishment of marine protected areas, and stricter management of bycatch in commercial fisheries.

Public awareness also plays a role. Sharks often get a bad reputation as dangerous predators, but they are crucial to the ocean’s health. Educating people about their ecological importance can help shift public attitudes and encourage stronger conservation policies.

Encouragingly, the researchers note that positive change doesn’t take centuries. In as little as a few decades, shark populations could begin to recover if nations commit to sustainable fishing and stronger protections.

Why This Study Matters Beyond Sharks

The findings echo a broader pattern seen across nature: the specialists are often the first to disappear, while the generalists survive. This has been observed in birds, mammals, and even plants. As environments change rapidly due to human activity, species that rely on very specific habitats or diets can’t adapt as easily.

In the case of sharks, this means that many of the most fascinating, highly adapted species could vanish, leaving behind a simplified ocean ecosystem. It’s a stark reminder that evolution’s most creative outcomes—like hammerheads, thresher sharks, or lanternsharks—are also the most vulnerable to human impact.

A Future Worth Protecting

The message from Stanford’s research is both sobering and hopeful. If current extinction trends continue, the ocean could become a place filled with fewer shapes, fewer sizes, and fewer stories of evolutionary innovation. But with swift and coordinated global action, it’s still possible to protect these extraordinary animals and the ecosystems they sustain.

Sharks have survived mass extinctions, continental drift, and climate shifts. Whether they survive the current human-driven crisis depends on what we do next. Protecting the full spectrum of shark diversity isn’t just about saving wildlife—it’s about safeguarding the health of our planet’s oceans for generations to come.

Research Reference:

Extinction Threatens to Cause Morphological and Ecological Homogenization in Sharks – Science Advances (2025)