The Metabolic Cost of Life Shows How Cells Pay Hidden Energy Prices to Keep Biology on Track

Life runs on chemistry, but not all of its energy costs are obvious. A new scientific study takes a deep dive into what researchers are calling the “metabolic cost of life”—the hidden energetic price cells pay not just to run chemical reactions, but to keep the right reactions happening and prevent all the wrong ones.

At first glance, this might sound abstract. But it touches one of the most fundamental questions in biology and physics: why do living systems behave so differently from non-living ones, even when the same chemical laws apply?

The work, published in the Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment, introduces a new thermodynamic framework that finally puts numbers on these overlooked costs. It also opens a new window into understanding how early metabolic pathways may have been selected at the very origin of life.

Why Classical Physics Misses a Key Cost of Being Alive

In classical mechanics, energy costs are tied to motion and work. If nothing moves, no work is done, and therefore no energy is spent. Constraints—like walls, barriers, or fixed boundaries—are treated as passive. They simply exist and do not add to a system’s energetic balance.

Living systems clearly break this intuition.

Cells constantly maintain internal order, preserve boundaries, and channel chemical reactions along very specific routes. Photosynthesis, respiration, and countless metabolic processes do not simply happen by chance—they are carefully steered, while alternative reactions are actively suppressed.

From a classical perspective, this “steering” should cost nothing. But reality tells a different story.

Using tools from stochastic thermodynamics, the researchers show that preventing reactions from happening has a real energetic price. Keeping a biochemical pathway stable and exclusive is not free—it requires continuous investment.

Compartmentalization and the Birth of Metabolism

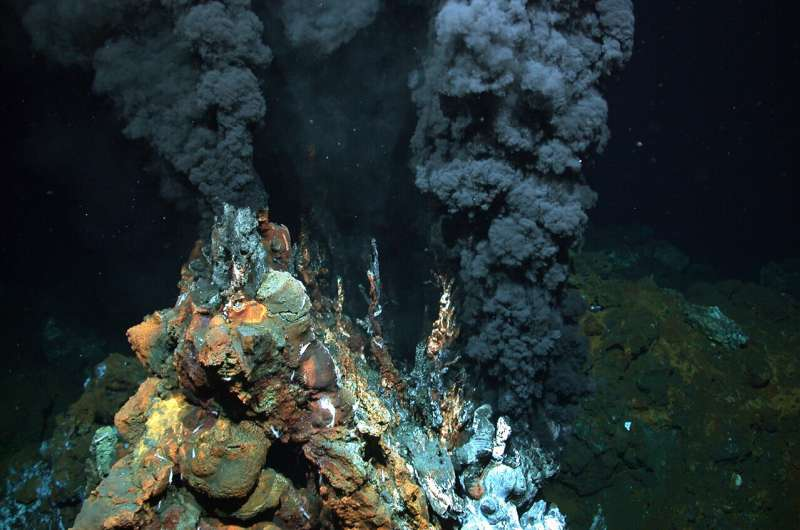

The study places strong emphasis on one of the most important steps in early evolution: the emergence of the first cell boundary.

When early organic molecules formed a membrane-like structure in the ancient oceans, a crucial distinction appeared for the first time—an inside and an outside. This simple separation changed everything.

From that moment on, the system had to:

- Maintain the boundary separating internal chemistry from the environment

- Select specific reactions that exploited incoming molecules

- Suppress countless alternative reactions that were chemically possible

Life, in other words, began together with continuous energetic effort.

Metabolism is not just about converting nutrients into products. It is also about choosing which chemical futures are allowed and which are forbidden.

The Two Hidden Costs of Metabolic Pathways

The new framework developed by the researchers quantifies metabolic costs using probability instead of classical energy accounting. The idea is simple but powerful: if a chemical process is extremely unlikely to happen on its own, then keeping it running steadily must cost a lot.

They break this into two distinct components.

Maintenance Cost

This measures how unlikely it is to sustain a constant chemical flow through a specific pathway. In a world governed only by spontaneous chemistry, stable and directed flows are rare. The more effort required to maintain that flow, the higher the cost.

Restriction Cost

This captures how unlikely it is to block all alternative reactions while allowing only the chosen pathway to operate. Chemical networks naturally branch out in many directions. Preventing that branching is energetically expensive.

Together, these two factors define the total thermodynamic cost of a metabolic pathway.

Ranking Pathways Instead of Guessing Them

One of the most powerful aspects of this work is that it allows scientists to compare and rank metabolic pathways objectively.

Given:

- A defined input (for example, CO₂)

- A defined output (such as glucose)

- The underlying chemical reactions

The method can generate all chemically possible pathways that connect input to output. Each pathway is then assigned a thermodynamic cost based on how improbable it would be to sustain under spontaneous chemistry.

This makes it possible to ask questions like:

- Why did life choose this pathway instead of another?

- Are naturally occurring pathways energetically efficient?

- What constraints shaped early metabolic evolution?

A Real-World Test Case: The Calvin Cycle

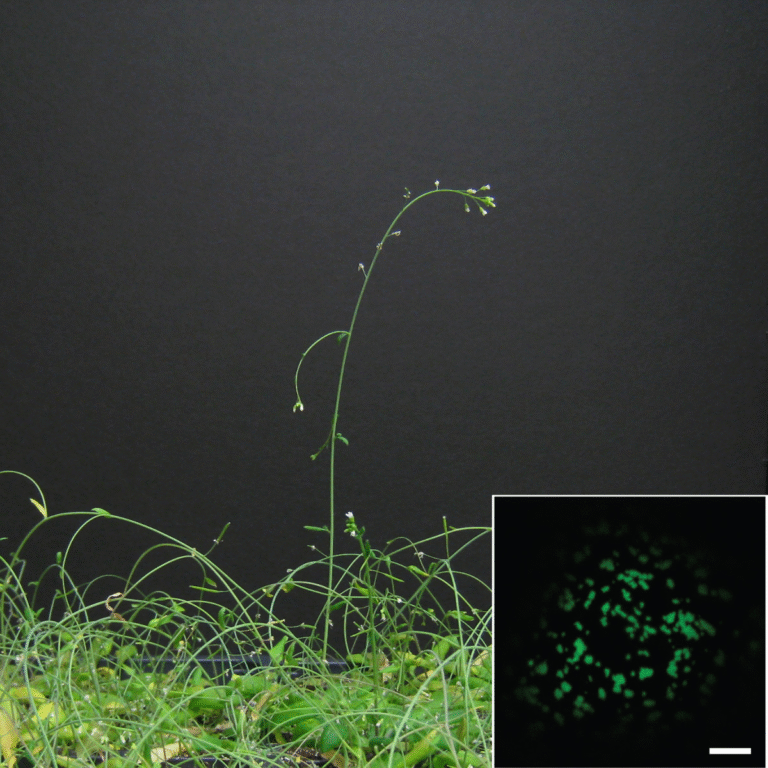

The approach builds on earlier work involving the Calvin cycle, the photosynthetic pathway plants use to convert carbon dioxide into sugars.

Using computational tools, researchers previously enumerated every possible chemical pathway that could achieve the same transformation. When these pathways were ranked using the newly defined maintenance cost, something remarkable emerged.

The pathway used by nature sits among the least dissipative and lowest-cost options.

In other words, evolution appears to have selected a solution that is thermodynamically efficient, not just chemically feasible.

Surprising Results About Multiple Pathways

One unexpected result of the analysis is that using multiple pathways at the same time can actually reduce cost.

The logic is similar to traffic flow. If too many reactions compete for the same narrow chemical “channel,” they slow each other down. Spreading reactions across multiple routes can reduce congestion and energetic burden.

Yet biology often favors one dominant pathway.

Why?

The answer lies beyond thermodynamics alone. Biological systems rely heavily on enzymes, which accelerate specific reactions and effectively lower their cost. Maintaining multiple pathways also comes with drawbacks, such as:

- Producing toxic intermediate molecules

- Requiring more regulatory control

- Increasing the complexity of the system

Evolution balances energetic efficiency with chemical safety and stability.

Why This Matters for Origin-of-Life Research

This framework offers something researchers have long lacked: a way to quantify the energetic price of biological choice.

It helps explain:

- Why some metabolic pathways emerged early

- Why others were never adopted

- How energetic constraints shaped biological complexity

Rather than treating constraints as free, the model recognizes them as active, costly features of life.

This is especially important for origin-of-life studies, where researchers try to understand how non-living chemistry crossed the threshold into self-sustaining biology.

Broader Implications Beyond Early Life

While rooted in evolutionary questions, the method has relevance far beyond ancient biology.

It could influence:

- Synthetic biology, by helping design energetically efficient metabolic networks

- Metabolic engineering, where pathway optimization is critical

- Systems biology, by offering a deeper thermodynamic understanding of regulation and control

The study also highlights how living systems fundamentally differ from mechanical ones—not by breaking physical laws, but by paying energetic prices that classical physics tends to ignore.

A Tool, Not a Final Answer

The researchers emphasize that their method is not a complete explanation for why specific pathways exist. Instead, it is a powerful new tool that adds thermodynamic clarity to evolutionary questions.

Understanding why life chose particular solutions will always require a multidisciplinary approach—combining chemistry, physics, biology, and evolutionary theory.

What this work provides is a way to finally measure the hidden costs of staying alive.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-5468/ae22eb