Tightening the Focus of Subcellular Snapshots With a Smarter Way to Prepare Cell Slices for CryoET Imaging

Taking detailed images of what’s happening inside a cell is one of the toughest challenges in modern biology. Cells are crowded, complex, and incredibly small, and many of the structures scientists want to study are even smaller and rare. A recent study introduces a significant improvement to how researchers prepare cellular samples for cryogenic electron tomography (cryoET), a powerful imaging technique that reveals the inner architecture of cells in three dimensions. By combining light microscopy, focused ion beam milling, and a clever use of optical interference, scientists have found a way to target tiny structures inside cells with much higher precision than before.

What CryoET Is and Why Sample Preparation Is So Difficult

CryoET is one of the most advanced tools available for studying cells. It works by firing electrons through a frozen biological sample. The electrons that pass through the sample are used to reconstruct a 3D image of the cell’s interior at near-atomic resolution. This allows researchers to see how cellular machinery is arranged in its natural state, without the distortions caused by chemical fixation or staining.

However, there’s a major limitation. Electrons cannot easily pass through thick samples, and most cells, including human cells, are simply too thick for direct cryoET imaging. To solve this, scientists use a focused ion beam (FIB) to carefully mill the frozen cell down into ultrathin slices, typically about 200 nanometers thick. These slices, called lamellae, are thin enough for electrons to pass through.

The real challenge comes next. Cells are large compared to many of the structures scientists care about. If the milling process misses the exact location of the target structure — such as a ribosome, chloroplast, or virus — the final slice may be useless. Researchers often have to mill multiple lamellae before successfully capturing what they’re looking for, which costs time, effort, and precious samples.

A New Way to Guide Milling With Light

Researchers at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, working in collaboration with Stanford University, have developed a method that dramatically improves the accuracy of this milling step. Their approach combines fluorescence light microscopy with focused ion beam milling in a way that allows scientists to know exactly where their target is inside the final thin slice.

The key improvement is the use of an additional optical signal that comes from interference effects in fluorescent light. This signal provides precise information about the depth of a fluorescently labeled structure inside the cell as milling progresses.

According to the study, this method improves the accuracy of optically guided milling by roughly an order of magnitude, making it far more reliable when targeting small and rare structures.

How the Tri-Coincident System Works

At the heart of this advance is a setup known as a tri-coincident system. In this configuration, three instruments are carefully aligned so that they all focus on the same point in space:

- A scanning electron microscope for surface imaging

- A focused ion beam for milling the cell

- An optical fluorescence microscope for visualizing tagged structures

Most commercial systems do not have these components fully co-aligned, which means fluorescence images are usually taken separately and then matched to milling coordinates later. That matching process introduces errors. In contrast, the tri-coincident system allows researchers to observe fluorescence in real time while milling is happening.

There is still a fundamental problem, though. Standard optical microscopy cannot reliably resolve objects smaller than about 200 nanometers due to diffraction limits. Many biological targets fall below this size.

This is where optical interference comes into play.

Using Optical Interference to Beat Resolution Limits

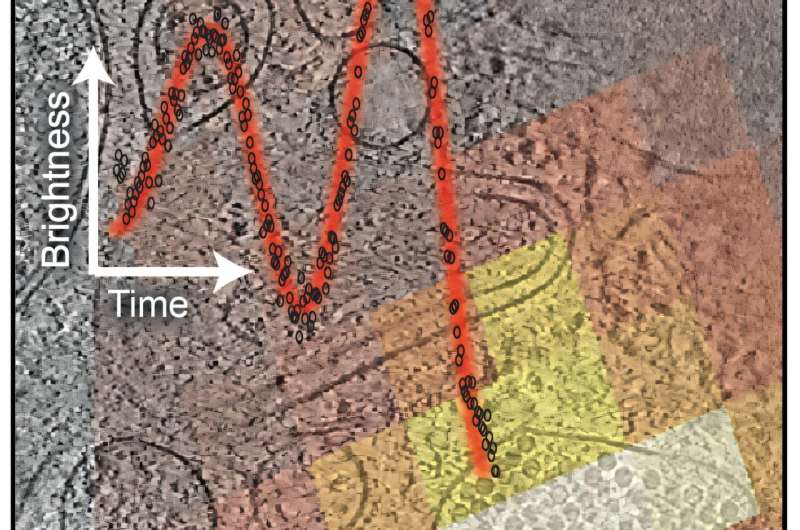

As the ion beam mills away the top of a frozen cell, fluorescent light emitted from labeled structures inside the cell travels upward. Some of this light reflects off the freshly milled surface and travels back down, where it interferes with incoming light waves. This interference causes the detected fluorescence signal to brighten and dim in a predictable pattern as the distance between the milling surface and the fluorescent object changes.

By carefully analyzing these oscillations, software developed by the research team can calculate the object’s position along the vertical axis with remarkable accuracy, even when the object itself is smaller than the optical resolution limit.

This interference-based signal effectively acts as a depth ruler, telling researchers when to stop milling so the final slice contains the structure of interest.

Proving the Method With Viral Imaging

To demonstrate the power of their approach, the researchers targeted a 26-nanometer-wide virus infecting a human cell. Viruses of this size are notoriously difficult to capture with cryoET because they are both tiny and relatively rare within a cell.

Using the interference-guided milling method, the team successfully prepared lamellae that contained the virus, making it possible to image structures that were previously considered out of reach for routine cryoET studies.

This success shows that the technique can be applied to a wide range of small, transient, or sparsely distributed cellular structures, including other viral particles and components involved in cell division.

Why This Matters for CryoET and Cell Biology

This new approach brings several important advantages:

- Higher success rates when targeting specific structures

- Reduced milling time, since fewer failed attempts are needed

- Less sample waste, which is critical for rare or hard-to-grow cells

- More accurate targeting without relying on external markers

For the field of cryoET, this means researchers can now ask more ambitious questions about how cells function at the nanoscale, especially when studying interactions between host cells and pathogens.

Extra Context: Why CryoET Is So Valuable

CryoET has become a cornerstone technique in structural biology because it bridges the gap between molecular and cellular scales. Unlike single-particle cryo-electron microscopy, which focuses on isolated proteins, cryoET preserves the native cellular environment. This makes it especially valuable for studying processes like viral entry, intracellular transport, and organelle organization.

As imaging hardware improves, sample preparation has increasingly become the bottleneck. Innovations like interference-guided milling are essential to unlocking the full potential of cryoET and making it more accessible to a wider range of biological questions.

Looking Ahead

The research team plans to further enhance the system by incorporating advanced fluorescence microscopy techniques into the tri-coincident setup. These additions could improve optical image quality even more and provide richer information to guide cryoET imaging.

With continued development, this approach could become a new standard for preparing cryoET samples, especially when precision is critical.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-65548-8