Tracer Reveals How Environmental DNA Moves Through Lakes and Rivers

Environmental DNA, often shortened to eDNA, has quietly become one of the most powerful tools in modern ecology. By collecting tiny fragments of genetic material shed by organisms into water, soil, or air, scientists can detect which species are present without ever seeing or catching them. Now, a new study has taken this idea a big step further by answering a long-standing question: how does eDNA actually move through large bodies of water like lakes and rivers?

A team of ecologists and engineers from Cornell University and the University of Granada has developed a clever way to track eDNA as it disperses in real aquatic environments. Their work, published in the journal Environmental Science & Technology, sheds light on how far DNA can travel, how long it stays detectable, and how scientists might trace it back to its source. This breakthrough has major implications for conservation, biodiversity monitoring, and environmental management.

Understanding the Challenge of eDNA in Water

Environmental DNA has already transformed wildlife monitoring. Over the past 15 years, advances in molecular biology have expanded eDNA from detecting a single species to community-wide biodiversity surveys. Compared to traditional methods like netting fish or visually surveying habitats, eDNA is faster, cheaper, less invasive, and often more sensitive.

However, eDNA comes with a serious challenge. In large lakes, rivers, and marine environments, water is constantly moving due to currents, wind, waves, and mixing across depths. This means DNA detected at one location may not have come from a nearby organism. For scientists and regulators, this raises a critical question: when and where was that DNA actually released?

Without knowing how far eDNA can travel or how it behaves once released, interpreting results becomes difficult—especially when decisions about endangered species or invasive organisms are at stake.

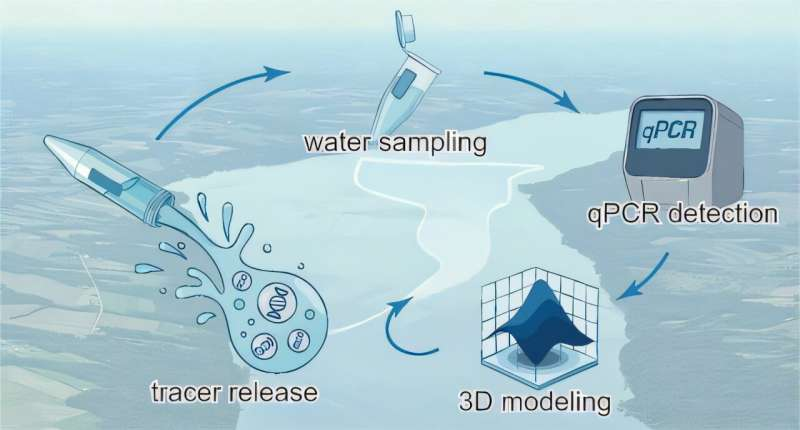

A Synthetic DNA Tracer Experiment in Cayuga Lake

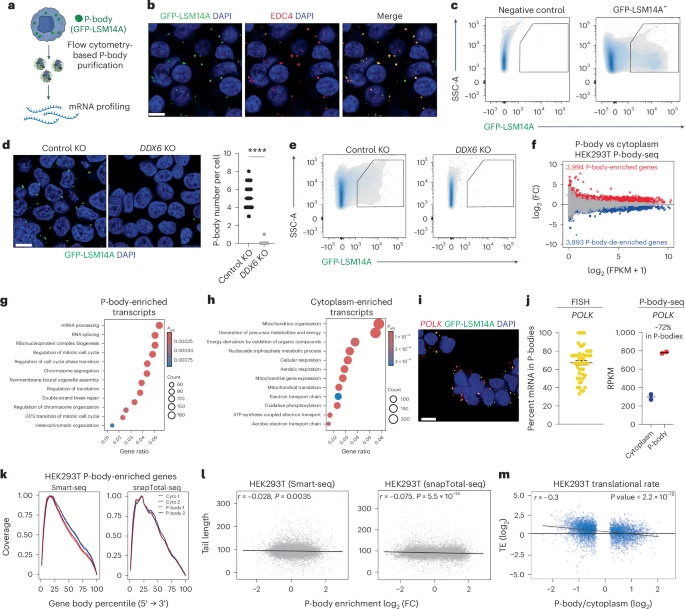

To tackle this problem, researchers designed a synthetic DNA tracer that behaves like real environmental DNA but can be easily identified and tracked. The tracer was developed by Zeyu Li, the study’s first author and a doctoral student working under Dan Luo, a professor of biological and environmental engineering at Cornell.

The synthetic DNA consisted of short, unique DNA sequences that do not naturally occur in the environment. These sequences were encapsulated inside a safe, biodegradable polymer commonly used in the food and pharmaceutical industries. This ensured the tracer posed no environmental risk while closely mimicking the physical behavior of natural eDNA particles.

Only 1 microgram of DNA—about one-thousandth of a gram—was released into Cayuga Lake, a large freshwater lake near Cornell’s Ithaca campus. After the release, researchers tracked the tracer’s movement for 33 hours, collecting water samples across different locations and depths.

Combining Field Data With Hydrodynamic Modeling

What makes this study especially powerful is how the field experiment was paired with advanced hydrodynamic modeling. The research team used detailed computer models to simulate how water moves within the lake, accounting for wind-driven circulation, vertical mixing, and horizontal currents.

By integrating real-world measurements with these models, scientists could predict where a detected DNA particle was most likely released. This approach allowed them to explore both forward tracking (where DNA goes after release) and backward tracking (where detected DNA might have originated).

The results showed that eDNA can travel kilometers away from its source in a relatively short time. The tracer was detected more than 7 kilometers from the release point, even at very low concentrations—sometimes as few as three to five particles per milliliter of water. This demonstrates both the durability of eDNA and the sensitivity of modern detection methods.

Why Depth Matters More Than Expected

One of the most important findings was the role of vertical position in the water column. While horizontal movement across the lake could be modeled with reasonable accuracy, small differences in depth significantly affected predictions of where the DNA came from.

In other words, knowing how deep the DNA was when released is often more important than knowing how far it traveled horizontally. This insight helps explain why eDNA studies in large, deep, and well-mixed environments can sometimes produce confusing or misleading results if depth is ignored.

A Game Changer for Aquatic Ecology

The study brought together expertise in genetics, engineering, ecology, and fluid dynamics, allowing the team to address the problem from multiple angles. According to the researchers, this kind of high-resolution analysis of dispersion, transport, and fate in aquatic environments is essential for managing freshwater, estuarine, and coastal resources.

The approach is also highly scalable. Similar experiments could be conducted in Lake Ontario, coastal waters, or even the open ocean. The synthetic DNA tracer system is flexible, safe, and adaptable to different environments.

What This Means for Conservation and Policy

Environmental DNA is already influencing real-world decisions, and this research makes it even more useful. For fish and wildlife managers, eDNA offers a practical alternative to labor-intensive surveys that require capturing animals or deploying expensive equipment.

With better models of how eDNA moves, regulators could use genetic data to:

- Estimate population sizes of endangered or protected species

- Track invasive species before they become established

- Assess environmental impacts of offshore energy projects

- Monitor commercially exploited fish populations

- Detect biological introductions from cargo ships

As biodiversity loss accelerates in aquatic ecosystems worldwide, scalable tools like eDNA are becoming essential. Better understanding how eDNA behaves in water helps ensure that management decisions are based on accurate interpretations, not misleading signals.

What Is Environmental DNA and Why It Matters

Environmental DNA refers to genetic material shed by organisms through skin cells, mucus, feces, reproductive material, or decay. In aquatic systems, this DNA disperses through water and can persist for hours to days, depending on conditions.

Scientists typically collect water samples, filter them, and use quantitative PCR or sequencing techniques to identify which species are present. Because eDNA does not require direct contact with organisms, it is especially valuable for monitoring rare, elusive, or endangered species.

However, until recently, scientists lacked solid data on how eDNA moves in large, dynamic water bodies. This new research helps close that gap by providing a quantitative, experimentally validated framework for understanding eDNA transport.

Looking Ahead

The combination of synthetic DNA tracers and hydrodynamic modeling represents a major step forward for environmental science. It transforms eDNA from a simple detection tool into a method capable of offering spatial and temporal context.

As the technology evolves, future studies may refine models further, explore different types of aquatic systems, and help integrate eDNA data more confidently into policy, conservation planning, and environmental regulation.

For now, this work stands as a clear demonstration that understanding how DNA moves through water is just as important as detecting it in the first place.

Research paper:

https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.5c11071