Two Harmful Gene Variants Can Restore Function When Combined, Study Reveals

Sometimes, genetics refuses to follow simple rules. A new study has shown that two gene variants that are harmful on their own can surprisingly restore normal function when they occur together. This finding confirms a long-standing hypothesis in molecular biology and opens the door to a major shift in how scientists and clinicians interpret genetic data.

The research, led by scientists at George Mason University in collaboration with the Pacific Northwest Research Institute (PNRI), provides direct experimental evidence for a phenomenon that had existed mostly as a theoretical idea for decades. The study also introduces a powerful AI-driven framework capable of predicting these unexpected genetic interactions across different genes.

At its core, the work challenges one of the most common assumptions in genetics: that combining two damaging mutations will always make things worse. As it turns out, biology is far more nuanced.

Understanding the Hidden Complexity of Genetic Variation

Human genomes are extraordinarily complex. Each person carries billions of DNA base pairs, and between any two individuals, there are roughly five million genetic variants. Modern genomic sequencing has made it relatively easy to identify these variants, but understanding what they actually do remains a major challenge.

Most current genetic interpretation tools focus on single variants, analyzing how one change affects a gene or protein. This approach has been useful, but it leaves out an important piece of the puzzle: genes do not operate in isolation. Variants can interact with each other, sometimes in unexpected ways.

This interaction between variants is known as epistasis, and it has long been suspected to play a significant role in both health and disease. However, experimentally measuring epistasis is extremely difficult, which is why it has been largely ignored in clinical genomics until now.

The Study That Put Epistasis to the Test

The project began when geneticist Aimée Dudley from PNRI approached George Mason University’s Chief AI Officer Amarda Shehu. Dudley’s lab specializes in high-throughput experimental genetics, while Shehu’s lab focuses on advanced artificial intelligence models for interpreting biological data. Together, they set out to explore whether variant combinations could explain some puzzling genetic observations.

The team focused on a key metabolic enzyme called argininosuccinate lyase (ASL). This enzyme plays a critical role in the urea cycle, a process that removes toxic ammonia from the body. Defects in ASL cause urea cycle disorder, a rare but severe genetic condition that often presents in infancy and can be fatal if untreated.

Researchers systematically tested thousands of variant combinations within the ASL gene. Each individual variant tested caused a complete loss of enzyme activity on its own. But when certain pairs of these harmful variants were combined, something remarkable happened.

A significant fraction of these pairs showed high levels of restored enzyme function. In practical terms, two broken variants combined to behave like a functional gene.

Why Two Wrongs Can Make a Right

This unexpected recovery of function is explained by a concept known as variant sequestration, sometimes also referred to as intragenic complementation. The idea was originally proposed decades ago by Nobel laureate Francis Crick, but until this study, it had never been demonstrated so clearly in a human disease-related gene.

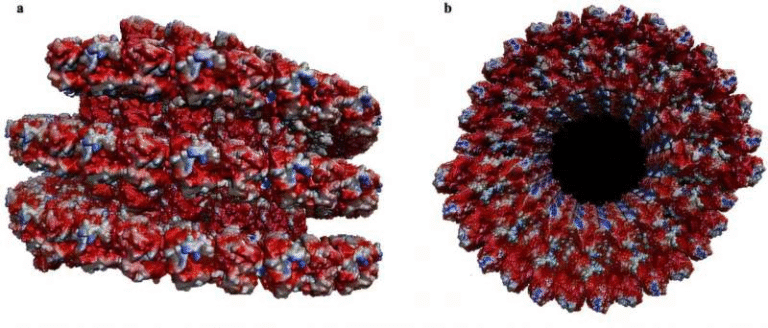

ASL functions as a multimeric protein, meaning it forms a complex structure made up of multiple subunits. The study found that different variants tend to affect different spatial regions of the protein. When two variants disrupt separate functional areas, they can essentially “cancel out” each other’s defects by occupying different subunits or active sites.

Structural analysis revealed distinct functional regions within the protein. When variants were distributed across these regions, the protein could still assemble and function correctly. This spatial separation is the key to why function can be restored.

This finding confirms that protein structure matters just as much as DNA sequence, especially when it comes to understanding how variants interact.

The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Scaling the Discovery

Once the experimental results were established, the George Mason University team turned to artificial intelligence to see if these effects could be predicted computationally.

Using the ASL data, computer science Ph.D. student Anowarul Kabir developed a machine learning model trained to recognize patterns in both protein sequence and three-dimensional structure. The goal was to predict whether a given pair of variants would result in functional recovery.

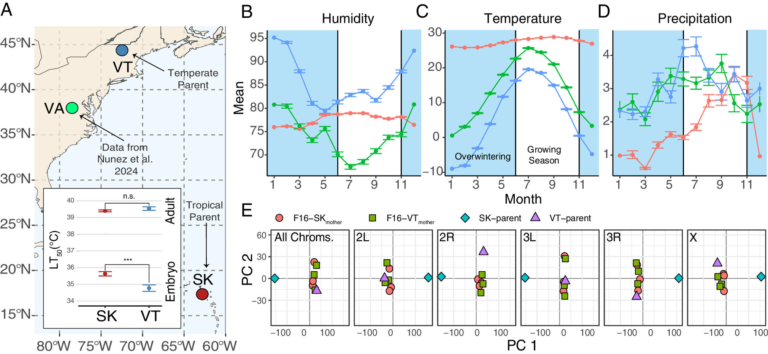

The results were striking. The model achieved 99.6% accuracy in predicting which ASL variant combinations would regain function. To test whether the model could generalize beyond a single gene, the team applied it to fumarase (FH), a structurally similar but evolutionarily distinct enzyme involved in cellular metabolism.

Even without direct experimental training data for FH, the model achieved 91% accuracy in predicting functional recovery. This demonstrated that the AI had learned transferable structural and functional rules, not just gene-specific quirks.

How Widespread Could This Be?

One of the most intriguing implications of the study is its potential scope. Based on their analysis, the researchers estimate that around 4% of genes in the human genome could exhibit similar compensatory interactions between harmful variants.

This suggests that many genetic conditions may be more complex than currently appreciated. Some individuals who appear to carry multiple damaging mutations might actually retain partial or full gene function due to these hidden interactions.

For clinical genomics, this is a game changer.

Why This Matters for Precision Medicine

Today, genetic diagnoses often rely on identifying single pathogenic variants and labeling them as disease-causing. This study shows that such an approach can be incomplete or even misleading.

By ignoring variant combinations, clinicians may overestimate disease severity or miss opportunities for targeted treatments. Incorporating epistasis into genetic interpretation could lead to more accurate diagnoses, better risk assessment, and improved treatment strategies.

The findings also open the door to more refined clinical trials. Instead of grouping patients based on single mutations, researchers could stratify participants based on epistatic profiles, improving the chances of detecting treatment effects.

Beyond Diagnosis: New Directions for Research

This work also has broader implications for evolutionary biology, protein engineering, and drug development. Understanding how proteins tolerate or compensate for mutations could inform the design of more robust enzymes or therapies that exploit compensatory mechanisms.

It also highlights the growing importance of combining experimental biology with artificial intelligence. High-throughput experiments generate massive datasets, and AI provides the tools needed to extract meaningful patterns from them.

In this case, AI did not replace experimentation but amplified its impact, allowing insights from one gene to be extended across many others.

A Shift in How We Think About Genes

For decades, genetics has largely been framed as a one-variant-at-a-time discipline. This study makes a compelling case that such simplicity does not reflect biological reality.

Genes operate in networks. Proteins function in three-dimensional space. Variants interact, sometimes destructively, sometimes constructively. Recognizing this complexity is essential if precision medicine is to live up to its promise.

By proving that two harmful variants can restore function, this research forces a rethink of what it really means for a gene to be “broken.”

Research paper: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2516291123