Vocal Comprehension Learning Is Far More Widespread in Birds Than Scientists Once Believed

A new review published in The Quarterly Review of Biology is challenging long-held assumptions about how birds learn and understand sounds. For decades, the scientific focus has been on a small set of birds—songbirds, parrots, and hummingbirds—because these groups are known for their ability to learn to produce new sounds. But this new article argues that the ability to understand sounds, known as vocal comprehension learning, is actually far more common across the bird world than the ability to produce novel vocalizations. In fact, the research suggests that comprehension learning may form the evolutionary foundation upon which more complex vocal behaviors, including human language, eventually developed.

The paper, titled “Vocal Contextual Learning in Birds” and authored by William A. Searcy and Eleanor M. Hay of the University of Miami, reviews decades of scientific work to evaluate how birds learn the meanings of sounds through experience. Their findings reveal that at least 17 of 37 avian orders show natural, real-world evidence of vocal comprehension learning—spanning nearly every major branch of the global bird family tree. This means that the ability to interpret sounds is not limited to a few advanced species but may be an ancient and widespread trait that emerged early in bird evolution.

The authors highlight that the skill of interpreting sound is generally much better developed than the ability to encode new information in vocalizations. In simple terms, many types of birds can learn what sounds mean, even if they cannot learn to make new sounds themselves. This insight significantly expands the scientific understanding of how birds communicate and how vocal abilities evolve over time.

Examples of Vocal Comprehension Learning in Nature

Across hundreds of studies, Searcy and Hay point to numerous real-world examples that demonstrate just how sophisticated birds can be when it comes to interpreting vocal information.

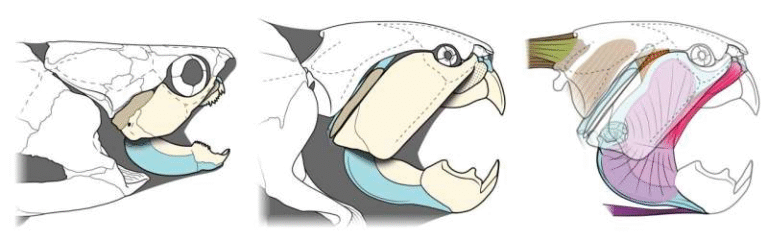

- Mate recognition in gulls: Several gull species can identify their mates strictly through vocal cues. Even in noisy environments, these birds distinguish the unique sound profiles of their partners.

- Parent-chick recognition in penguins: Penguin parents locate their offspring in densely packed colonies using individual signature calls. These calls allow them to find their chicks among thousands of nearly identical juveniles.

- Eavesdropping in songbirds: Many songbird species listen to aggressive or courtship interactions happening between other birds and use this information to better understand social relationships in their environment. This behavior helps them decide when to defend territory, when to avoid conflict, and which individuals pose a threat.

- Third-party knowledge in acorn woodpeckers: The cooperatively breeding acorn woodpecker shows an ability scientists call third-party knowledge. These birds can keep track of social relationships between other members of their group, even when they are not directly involved. This level of social awareness is rare among non-human species.

These examples demonstrate that comprehension learning is not just a laboratory phenomenon—it is something birds naturally rely on for social organization, survival, mate recognition, and navigation through complex environments.

Why Vocal Usage Learning Is Much Rarer

The review also discusses another type of learning: vocal usage learning, which refers to when a bird learns to modify the context in which it produces specific vocalizations. Unlike comprehension learning, usage learning appears in only four avian orders, and often only under laboratory conditions.

Many of the best-known examples come from training experiments, such as African gray parrots that can learn to label colors, shapes, or numbers. While these cases are famous, they are not typical of how most birds behave in nature.

A few natural examples exist:

- Canebrake wrens learn new duet patterns after forming new breeding pairs.

- Zebra finches adjust call timing to avoid overlapping with the songs of nearby birds.

Even so, the paper stresses that usage learning is “strikingly rare,” especially when compared to the widespread presence of comprehension learning. The authors note that many natural signaling systems in birds are so simple—often involving only two categories of calls—that learning may not be needed for correct vocal usage.

Evolutionary Insights From the Study

The authors performed evolutionary analyses to determine how vocal behaviors may have developed over time. Their results suggest that vocal comprehension learning likely evolved very early in bird evolution. Meanwhile, vocal usage learning evolved later and in a more scattered manner.

Because comprehension learning offers clear survival benefits—such as recognizing mates, chicks, predators, or neighbors—this skill may have been strongly selected for over millions of years. Birds that could interpret sound-based information had better chances of successful reproduction, effective parenting, and efficient social navigation.

This insight supports a broader idea: understanding sound may be a more fundamental and ancient adaptation than producing new sounds.

What This Means for Understanding the Origins of Language

One of the most intriguing implications of the paper is how it relates to the evolution of human language. Traditionally, scientists have used vocal production learning in birds as an analogy for how humans learn to speak. But if comprehension learning is more widespread and evolutionarily older, it may represent a closer parallel to the earliest stages of human language development.

The authors suggest that language may have first emerged through the expansion of comprehension abilities—the ability to extract meaning from sound—long before humans developed complex syntax or flexible vocal production. Only later would more elaborate vocal usage patterns have appeared.

This viewpoint reframes the study of language evolution by highlighting the importance of understanding meaning rather than focusing solely on producing new vocal forms.

Additional Context About Vocal Learning in Birds

To better appreciate the significance of the new research, it helps to understand how scientists have traditionally approached vocal learning.

Historically, the field has centered on production learning, especially in songbirds, parrots, and hummingbirds. These species share a specific neural architecture that supports learning and producing novel vocalizations. Specialized brain structures, such as the HVC region in songbirds, have been studied extensively.

However, these structures are not present in most other birds, leading researchers to assume that vocal learning was uncommon outside these specialized groups. The new review challenges that assumption, presenting evidence that comprehension learning does not depend on the same neurological systems used for song production. This suggests that many bird species have evolved flexible sound-interpretation abilities through different mechanisms.

It also supports the growing belief among researchers that vocal learning is not simply all-or-nothing. Instead, it exists on a spectrum, ranging from innate calls to learned usage and learned comprehension. This spectrum may also apply to other animals, including humans.

Where Future Research Is Needed

The authors highlight several areas where more scientific work is necessary:

- Understanding neural mechanisms behind comprehension learning.

- Conducting controlled experiments with more non-songbird species.

- Exploring complex vocal usage patterns in species with duet systems or intricate social structures.

- Clarifying how birds encode individual vocal identities, such as mate or chick signatures.

As research expands, scientists may discover even more bird species capable of learning meanings from sound, further reshaping our understanding of avian cognition.

Research paper:

Vocal Contextual Learning in Birds – The Quarterly Review of Biology (2025)