What Really Happens to Golden Eagles After Rehabilitation and Release Back Into the Wild

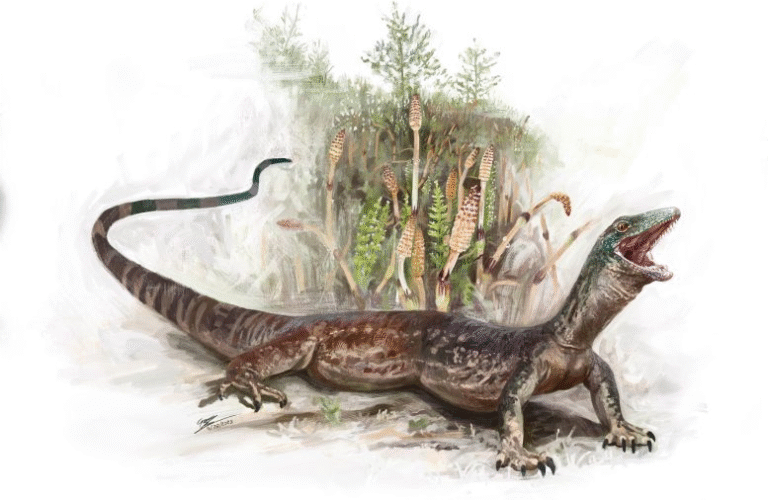

Rehabilitating injured wildlife often feels like a clear win for conservation. An animal is rescued, treated, and released, ideally returning to its natural role in the ecosystem. But when it comes to Golden Eagles, the reality after release is far more complicated. A new scientific study has taken a close look at what actually happens to these powerful raptors once they leave rehabilitation centers and re-enter the wild—and the results raise important questions for conservation policy, wildlife management, and how we measure success.

Golden Eagles face many human-caused threats, including electrocution from power lines, lead poisoning from ammunition fragments, vehicle collisions, wind turbine strikes, rodenticides, and illegal shooting. These pressures are increasing as human development spreads across their range in western North America. While some of these deaths are illegal, others occur as a byproduct of lawful activities such as energy infrastructure development.

Under the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act of 1962 (BGEPA), the United States recognizes a concept known as incidental take. This means that eagles may be injured or killed unintentionally during legal activities. When this happens, companies—such as electrical utilities or wind energy developers—can receive permits from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, but only if they take steps to minimize harm and offset eagle losses.

One potential offset strategy is the release of rehabilitated eagles back into the wild. Until recently, however, there was limited data showing whether this approach actually works.

A Close Look at Rehabilitated Golden Eagles

The study, titled “Post-Release Survival of Golden Eagles in Western North America Following Clinical Rehabilitation from Injury and Disease,” was published in the Journal of Raptor Research in 2025. Led by researcher Robert K. Murphy, the project involved collaboration with wildlife rehabilitators, state agencies, and conservation organizations across several western U.S. states.

The research team tracked 27 rehabilitated Golden Eagles that had been treated for injuries or illness and then released near their original rescue locations. Just before release, each eagle was fitted with a satellite transmitter, allowing scientists to monitor movements, survival, and causes of death in unprecedented detail.

The results were sobering.

Within the first year after release, 15 of the 27 eagles died, representing more than half of the study group. The fate of three additional eagles remained unknown, likely due to transmitter failure or loss of signal. Only nine eagles were confirmed alive after one year.

Causes of Death Reveal Persistent Threats

For most of the eagles that died, researchers were able to determine the cause. These causes closely mirrored the threats faced by wild eagles, including:

- Electrocution

- Vehicle collisions

- Wind turbine strikes

- Shooting

- Lead poisoning

- Rodenticide poisoning

- Starvation

Among these, starvation emerged as the most frequent cause of death for rehabilitated eagles. This finding is particularly notable because starvation is not a common cause of mortality among healthy, wild Golden Eagles. Researchers suspect that lingering physical or neurological impairments—undetectable during final health checks—may reduce an eagle’s ability to hunt effectively after release.

Survival Rates Compared to Wild Eagles

Using statistical survival models, the team estimated a first-year survival rate of 0.31 for rehabilitated Golden Eagles. In contrast, wild adult Golden Eagles typically show survival rates around 0.87 during the same time period.

This dramatic difference led to a critical conclusion: approximately 3.5 rehabilitated eagles must be released to equal the survival value of one wild adult eagle in population terms. This figure has major implications for how rehabilitation is used as a mitigation strategy under the BGEPA.

Breeding and Long-Term Success Remain Limited

Survival alone does not guarantee population recovery. Successful breeding is equally important. Of the 10 breeding-age eagles that survived for multiple years after release, none established consistent nesting territories, and only one eagle showed partial breeding behavior during a single season.

Two eagles displayed especially unusual behavior, embarking on long-distance movements of up to 5,300 miles, traveling in directions and seasons when Golden Eagles typically remain localized. Both birds eventually died. Researchers believe head trauma, sustained during vehicle collisions prior to rehabilitation, may have disrupted their orientation or navigation abilities.

Why Rehabilitation Outcomes Can Be Uncertain

Rehabilitation centers invest enormous effort, expertise, and funding into saving injured raptors. However, this study highlights an uncomfortable truth: clinical recovery does not always translate to ecological success.

Even subtle impairments can affect an eagle’s ability to:

- Capture prey efficiently

- Compete with other eagles

- Defend territories

- Navigate landscapes safely

- Locate mates and reproduce

These challenges help explain why rehabilitated eagles face a lower chance of long-term survival, despite appearing healthy at release.

Why This Research Matters for Conservation Policy

The findings provide much-needed data for wildlife managers and regulators. When incidental eagle deaths occur due to legal activities, decision-makers must determine how best to compensate for those losses. This study shows that while rehabilitation does contribute value, it cannot be treated as a one-to-one replacement for wild eagles.

The research also emphasizes that mitigation should not rely on rehabilitation alone. Preventing injuries in the first place—through safer power line designs, reduced lead ammunition use, better turbine placement, poison restrictions, and public education—is far more effective for maintaining stable populations.

The Bigger Picture: Why Golden Eagles Matter

Golden Eagles are apex predators, playing a crucial role in regulating prey populations and maintaining ecosystem balance. Their presence signals healthy landscapes, and their decline can ripple through entire food webs.

As human development continues to expand across the western United States, pressures on Golden Eagles are expected to increase. Understanding the limits of rehabilitation helps conservationists focus resources where they can have the greatest impact.

The study’s authors stress the need for further research, particularly into the breeding success and long-term contributions of rehabilitated eagles. Only with this information can conservation strategies evolve to meet the growing challenges these birds face.

Rehabilitation remains a valuable and compassionate tool—but as this research shows, saving Golden Eagles requires prevention, policy, infrastructure reform, and science working together, not just second chances after injury.

Research Paper Reference:

https://doi.org/10.3356/jrr2469