Where Kentucky’s Elusive Hellbenders Thrive and What They Need to Survive

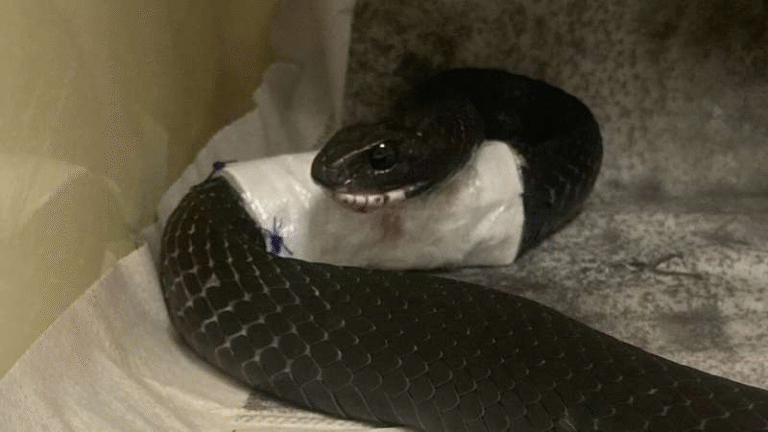

A new study from the University of Kentucky is shining light on one of the state’s most secretive creatures—the Eastern hellbender, a large, fully aquatic salamander sometimes affectionately called the “snot otter” or “lasagna lizard” because of its slippery skin and wrinkled folds. The research, published in Freshwater Biology (2025), dives deep into where these elusive amphibians still live in Kentucky and what their survival depends on.

A Statewide Search for a Vanishing Salamander

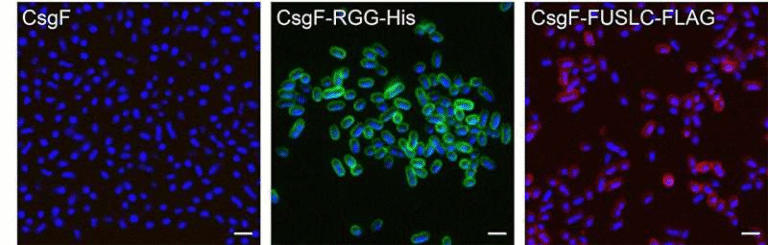

Led by Sarah A. Tomke during her Ph.D. in the Martin-Gatton College of Agriculture, Food and Environment, the project used environmental DNA (eDNA) to detect hellbenders across 90 sites in 73 rivers throughout Kentucky. eDNA is a relatively new technique that allows scientists to find traces of species by testing water samples for genetic material they shed—such as skin cells or mucus—rather than physically capturing or seeing them.

The researchers filtered water samples and tested for a hellbender-specific gene, creating one of the most extensive eDNA surveys ever conducted in the state. This method helps biologists identify where to focus fieldwork without disturbing heavy rocks or snorkeling for hours in cold, murky rivers.

What the Researchers Found

Hellbender DNA was detected at 22 sites across the state, including 12 rivers where the species had been historically recorded. These results gave researchers a clearer picture of the amphibian’s current distribution, showing that while the species still persists, its range has significantly contracted over the years.

To understand why hellbenders were present in some rivers but absent in others, the team analyzed how environmental factors affected both occupancy (whether hellbenders were actually there) and detection probability (how easily their DNA could be found). They discovered that local habitat quality mattered far more than broad-scale environmental factors like overall land cover or water chemistry.

Streams with clean, rocky bottoms—rich in cobble, gravel, and bedrock—were the most likely to host hellbenders. In contrast, areas where fine sediment filled the spaces beneath rocks were much less likely to have them. This sedimentation problem clogs the small shelters hellbenders rely on to hide, reproduce, and protect their larvae.

Interestingly, the study also found that streams with higher total organic carbon (TOC) in the water made eDNA harder to detect. This is important because it helps future researchers design more accurate surveys by understanding how water chemistry affects genetic sampling.

Timing Is Everything

The Kentucky team didn’t just look at where hellbenders live—they also tested when it’s best to look for them. Sampling across different seasons revealed that early fall, especially September, produced the strongest eDNA signals. This period coincides with the breeding season, when hellbenders shed more DNA into the water. For future studies and conservation work, that timing will make searches more efficient and successful.

Beyond the Lab: Confirming the Results

Although Tomke’s original study didn’t discover new populations beyond one well-documented site during her doctoral work, it served as a roadmap for conservation teams. Later, Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources biologists confirmed the presence of hellbenders at two streams that had tested positive for eDNA, proving that the genetic survey method worked as intended.

Department interim chair Steven Price called it the most comprehensive eDNA effort for hellbenders in Kentucky to date, helping to fill a long-standing information gap about where these animals remain.

Why Fine Sediment Is a Big Problem

Fine sediment might sound harmless, but for a species like the hellbender, it’s disastrous. Sediment can fill up the spaces under rocks where adults hide and larvae take refuge. Without these tiny shelters, the animals can’t survive long or reproduce effectively. Sediment comes from many sources—eroding streambanks, construction runoff, poorly managed farmland, and road ditches—all of which can wash into streams after heavy rains.

Price and his colleagues emphasize that keeping sediment out of streams is the single most important action people can take to protect hellbenders and other aquatic life. Steps like stabilizing eroding banks, replanting trees along streams, and improving farm and construction practices all make a measurable difference.

The Bigger Picture: Why Hellbenders Matter

Hellbenders aren’t just a curiosity—they play a crucial role in river ecosystems. As top predators of crayfish and insects, they help maintain balance in aquatic food webs. Their presence also acts as an early warning system for environmental health. When hellbenders disappear, it often signals that the water quality has deteriorated to the point that other species will soon follow.

These salamanders are also ancient survivors. Fossil evidence suggests that their ancestors have been around for millions of years, making their decline in modern times especially concerning. They are found across the Ohio River basin and Appalachian region, but their populations have dropped sharply throughout their range because of habitat loss, pollution, and disease.

Kentucky’s Hellbenders Today

Historically, hellbenders were widespread across Kentucky’s cool, well-oxygenated rivers. Today, sightings are rare, and holding one in the wild has become a special moment even for seasoned biologists. Adults can grow up to two feet long, making them one of North America’s largest salamanders. They prefer to stay hidden under broad, flat rocks in fast-flowing streams where the water stays clear and cold.

Because these conditions are becoming rarer due to sedimentation and human activity, protecting the remaining habitats is critical. The study’s results give conservationists a clear plan: reduce sediment, preserve rocky streambeds, and maintain healthy forested streambanks.

The Promise of eDNA

One of the most encouraging outcomes of the project is how well eDNA sampling worked. Traditional surveys involve turning over massive rocks or diving into rivers to search manually—methods that are not only labor-intensive but can also disturb habitats. eDNA allows researchers to test more sites, faster, and with less environmental impact.

However, eDNA isn’t foolproof. Water chemistry and sampling timing can influence results, and a lack of DNA in a sample doesn’t necessarily mean the species is absent. Still, when paired with habitat data, the technique gives scientists a much clearer picture of where to look next.

Looking Ahead

The University of Kentucky study provides a much-needed framework for managing and protecting one of the state’s most remarkable species. It shows that conservation success depends on local action—cleaning up sediment, restoring streambeds, and maintaining tree cover along waterways.

For local residents, landowners, and communities, this research offers practical steps: reduce soil runoff, plant trees near streams, and protect the natural rocky structure of rivers. Even small efforts can help rebuild the kind of clean, connected streambeds that hellbenders need to survive.

This project, supported by the McIntire-Stennis Cooperative Forestry Research Program of the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) and the Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources, is a reminder that science doesn’t just uncover data—it guides action.

By understanding exactly where hellbenders still live and what they need, Kentucky now has a roadmap to help one of its oldest residents thrive again. Clean water, rocky streams, and mindful land management aren’t just good for hellbenders—they’re good for everyone who depends on healthy rivers.