Why Don’t Antibiotic-Making Bacteria Self-Destruct When They Produce Powerful Drugs?

Early in 2025, scientists made a discovery that quietly reignited hope in the global fight against antibiotic resistance. A soil sample taken from a lab technician’s backyard led to the identification of a promising new antibiotic called lariocidin, produced by a naturally occurring bacterium from the Paenibacillus genus. What makes this discovery especially intriguing is not just the antibiotic’s ability to kill dangerous, drug-resistant bacteria, but the clever biological trick that allows the producer bacterium to survive its own lethal weapon.

The research, published in ACS Infectious Diseases, dives into a deceptively simple question: why doesn’t an antibiotic-producing bacterium kill itself? The answer reveals a highly specific self-defense mechanism that could shape how future antibiotics are designed and evaluated.

A New Antibiotic Found in an Unexpected Place

The discovery of lariocidin came from an effort to explore understudied soil bacteria, especially slow-growing microbes that are often overlooked in traditional antibiotic screens. Soil remains one of the richest natural sources of antibiotics, yet decades of searching have yielded diminishing returns. Many researchers now believe that untapped microbes, rather than exotic locations, may hold the key.

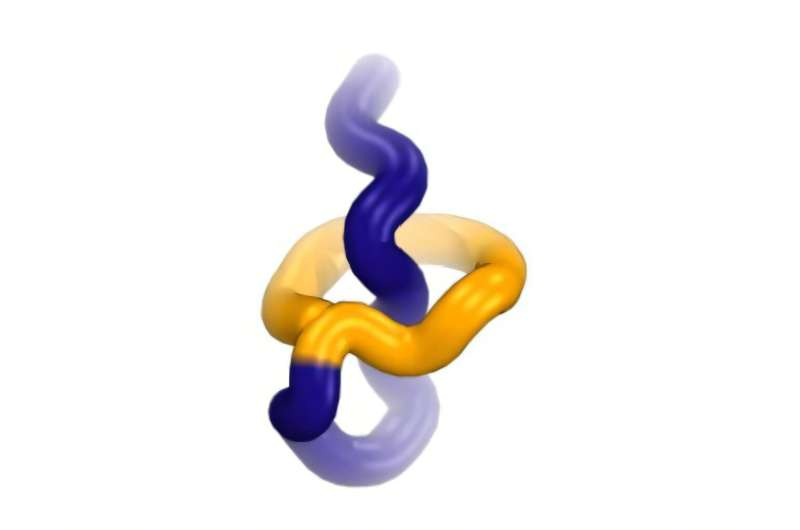

Lariocidin stood out almost immediately. It showed broad activity against pathogenic bacteria, including strains that are resistant to multiple existing drugs. This alone would be notable, but lariocidin also belongs to a rare group of compounds known as lasso peptides. These molecules have a distinctive structure that resembles a looped rope, where the tail of the peptide threads through a ring, forming a mechanically locked shape.

This unusual structure gives lariocidin exceptional stability, which is one reason scientists are excited about its therapeutic potential.

How Lariocidin Kills Other Bacteria

Lariocidin works by targeting one of the most essential components of bacterial life: the ribosome. Ribosomes are molecular machines made of ribosomal RNA and proteins, and they are responsible for building proteins inside the cell.

Specifically, lariocidin binds to ribosomal RNA and disrupts protein synthesis. Without the ability to make proteins, bacteria cannot grow or survive. This mechanism places lariocidin among a class of antibiotics that interfere with translation, but its binding site and molecular interactions are distinct from many existing drugs. That distinction matters, because it reduces the likelihood that bacteria already resistant to other antibiotics will automatically resist lariocidin as well.

The Big Question: Self-Resistance

Producing such a powerful antibiotic raises an obvious problem. If lariocidin shuts down ribosomes, why doesn’t it shut down the ribosomes of the bacterium that makes it?

To answer this, the researchers focused on the Paenibacillus strain responsible for lariocidin production. They suspected that the bacterium must possess a built-in resistance mechanism, and their experiments confirmed that suspicion.

The team identified a single enzyme, referred to as lrcE, that plays a critical protective role.

The Role of the LrcE Enzyme

The lrcE enzyme modifies lariocidin after it is produced. More specifically, lrcE adds a functional chemical group to the antibiotic molecule. This small modification has a big effect: it prevents lariocidin from binding to the bacterium’s own ribosomal RNA.

In simple terms, the bacterium produces a version of the antibiotic that is harmless to itself but remains lethal to competitors in the soil. Once released into the environment, lariocidin can exert its antibacterial effects on neighboring microbes that lack this protective enzyme.

One particularly encouraging finding is that lrcE is highly specific. It modifies lariocidin and does not interfere with other antibiotics such as aminoglycosides or streptothricins. This specificity suggests that resistance to lariocidin is not easily transferable to resistance against other drug classes.

What the Genome Reveals

To better understand the broader implications, the researchers analyzed the genetic blueprint of the Paenibacillus strain. They identified the gene responsible for producing the lrcE enzyme and then searched for similar genes in other organisms.

Their search uncovered related genes in some environmental bacteria, including certain Bacillus species and environmental proteobacteria. Importantly, no similar resistance genes were found in known human pathogens.

This matters because one of the biggest concerns in antibiotic development is the possibility of horizontal gene transfer, where resistance genes jump from harmless environmental bacteria to disease-causing ones. While such transfers do occur, the researchers emphasize that they are generally slow and rare, especially across very different bacterial populations.

Still, the team notes that if lariocidin or related compounds move toward widespread clinical use, ongoing surveillance for emerging resistance genes will be essential.

Why This Matters for Antibiotic Development

Discovering a new antibiotic is only the beginning. To assess whether a compound has real clinical potential, scientists must understand how resistance could arise. That is why uncovering the lrcE self-resistance mechanism is such a crucial step.

According to the researchers, studying self-resistance allows scientists to pressure-test the novelty of an antibiotic early in development. If resistance mechanisms are already widespread or easily transferable, the drug’s usefulness could be limited before it ever reaches patients.

In the case of lariocidin, the results are encouraging. The resistance mechanism appears highly specialized, uncommon in human pathogens, and not easily adaptable to other antibiotics. All of this strengthens the case for lariocidin as a next-generation antibiotic candidate.

A Closer Look at Lasso Peptide Antibiotics

Lariocidin belongs to a growing family of antibiotics called lasso peptides, which are attracting increased attention in drug discovery. These peptides are ribosomally synthesized, meaning they are built using the same basic machinery cells use to make proteins. After synthesis, they undergo precise chemical modifications that create their locked, lasso-like shape.

This structure gives lasso peptides several advantages. They are often highly stable, resistant to degradation, and capable of interacting with difficult biological targets. However, they have historically been challenging to develop as drugs due to production and delivery issues. Advances in synthetic biology and microbial engineering are now making it easier to explore their potential.

The Bigger Picture in Antibiotic Resistance

Antibiotic resistance remains one of the most urgent challenges in modern medicine. Many existing drugs are losing effectiveness, and the pipeline for new antibiotics has been dangerously thin for years.

Discoveries like lariocidin highlight an important shift in strategy. Instead of modifying old drugs, researchers are increasingly looking to novel structures, new targets, and natural microbial competition for inspiration. Understanding how bacteria naturally manage toxicity and resistance offers valuable clues for designing safer and more durable treatments.

What Comes Next

While lariocidin is still far from clinical use, the findings reported in ACS Infectious Diseases represent a significant step forward. Further research will need to address issues such as scalability, safety in humans, and long-term resistance risks. But for now, lariocidin stands out as a rare example of a truly novel antibiotic discovery, paired with a clear understanding of its self-resistance mechanism.

In a field where breakthroughs are increasingly rare, this study serves as a reminder that even ordinary soil can still hold extraordinary solutions.

Research paper:

https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsinfecdis.5c00885