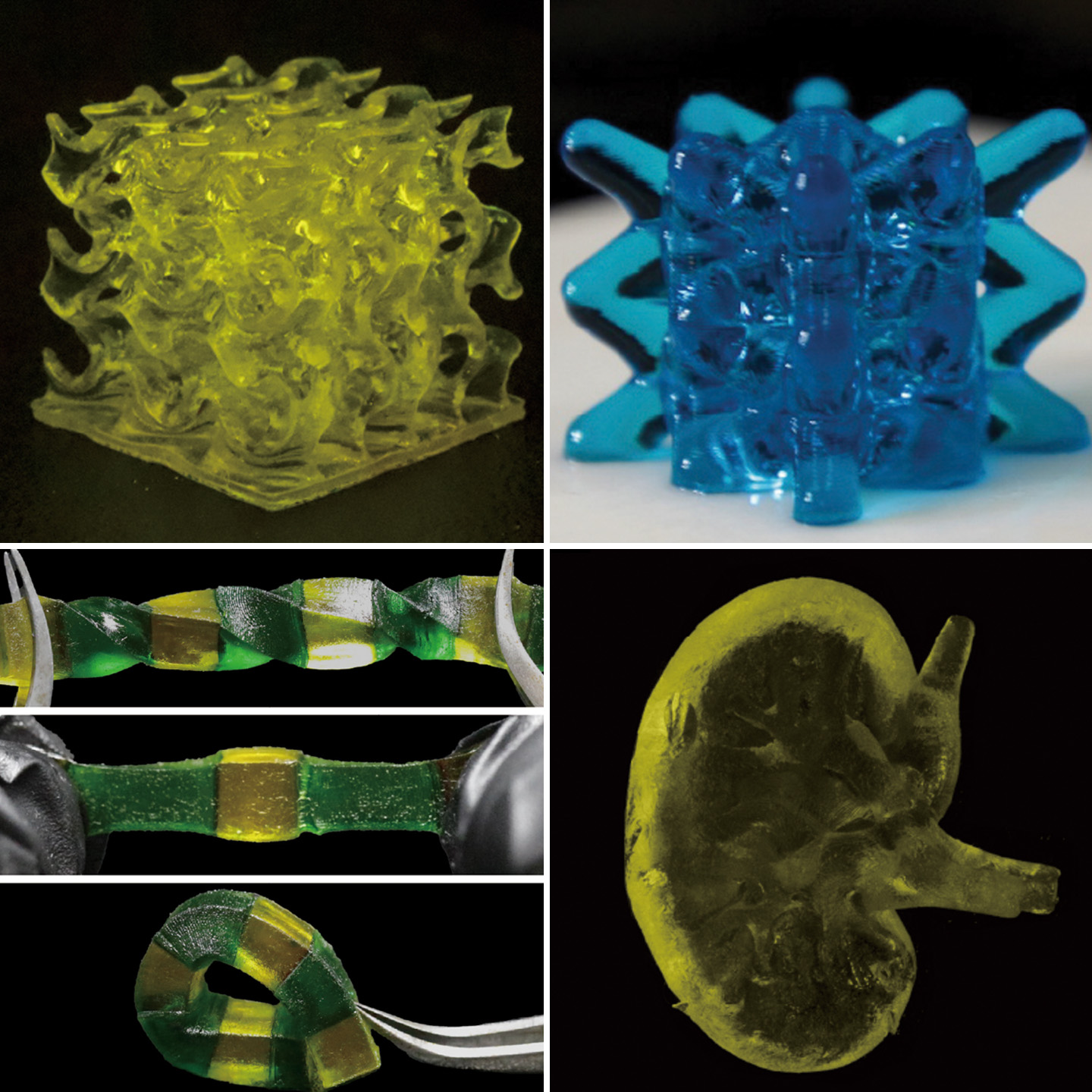

A Breakthrough 3D-Printable Polymer Brings Artificial Organs and Advanced Batteries Closer to Reality

A research team from the University of Virginia has developed a new 3D-printable polymer that could reshape the future of artificial organs, drug-delivery systems, and even next-generation batteries. What makes this development especially exciting is that the material is not only highly stretchable but also biocompatible, meaning it can exist alongside living cells without causing harm. This combination is rare, and it’s the main reason this breakthrough is gaining so much attention.

The research comes from the Soft Biomatter Laboratory at UVA, led by Liheng Cai, an associate professor of materials science and engineering and chemical engineering. The first author on the publication is Baiqiang Huang, a Ph.D. student in UVA’s School of Engineering and Applied Science. Their findings have been published in the journal Advanced Materials, and the details reveal a major leap forward in polymer design that solves long-standing limitations.

Understanding the Problem with Conventional PEG Materials

The team’s work focuses on polyethylene glycol, commonly known as PEG. PEG is already widely used in biomedical fields such as tissue engineering, implants, and drug delivery. It is valued for being safe, non-toxic, and compatible with biological systems.

But PEG has a major structural limitation.

Traditional PEG networks are made in water by crosslinking linear PEG polymers. Once the water is removed, the resulting structure becomes crystallized and brittle, especially in dry form. These materials can’t stretch much at all, and any meaningful strain causes them to break, crack, or lose integrity.

This brittleness prevents PEG from being used in applications that require flexibility, movement, or large, complex 3D shapes. In other words, it severely limits PEG’s potential—especially for soft robotics, synthetic organs, and flexible medical devices.

The UVA team set out to solve this problem by making PEG truly stretchable without sacrificing strength.

The Foldable Bottlebrush Architecture That Changes Everything

The key to this breakthrough is a molecular structure known as a foldable bottlebrush design.

Cai’s lab had previously developed methods for creating extremely strong and stretchable synthetic polymers by using internal molecular structures that store extra “hidden” length—similar to how a folded accordion can expand. Huang applied this concept specifically to PEG.

In this architecture:

- A central polymer backbone acts as the core.

- Many flexible side chains branch off like bristles on a bottlebrush.

- These side chains can collapse inward and unfold outward as needed.

- This unfolding stores and releases molecular “slack,” giving the material remarkable stretchability.

By using this architecture, Huang created PEG networks that are both strong and flexible, something traditional PEG materials fail to achieve.

To form this structure, the precursor solution is exposed to UV light for just a few seconds. This triggers polymerization and forms the bottlebrush network. Because the process is UV-driven, it can be used in 3D printing platforms—making the material ideal for custom shapes.

The result: highly stretchable PEG-based hydrogels and dry elastomers that maintain elasticity even at room temperature.

Why Stretchability Matters for Medical and Engineering Applications

This new stretchable PEG unlocks possibilities that were previously out of reach.

Flexible materials are essential for:

- Scaffolding for artificial organs

- Soft implants that can move with the body

- Wearable biomedical devices

- Drug-delivery implants that need to flex or expand

- Soft robotics for medical use

The ability to adjust both stiffness and softness—while maintaining stretch—means designers can create different parts of a structure with different mechanical properties. For example, one area of a printable organ scaffold can be stiff while another remains soft and flexible.

Another major advantage is that these materials are biologically friendly. In lab tests, cells cultured next to the PEG networks survived comfortably, proving that the polymer does not trigger obvious immune reactions. This biocompatibility is crucial for any material intended for human use.

Expanding Possibilities: Batteries and Beyond

While biomedical uses may be the most exciting application for many readers, the UVA team also discovered something important for energy technology.

Compared to existing solid-state polymer electrolytes, the new PEG materials show:

- Higher stretchability at room temperature

- Greater ionic conductivity

- Better mechanical flexibility under deformation

This suggests the material could work as a solid-state electrolyte in advanced battery technology. Today’s solid-state batteries often struggle with brittleness or poor performance when bent or stretched. A stretchable, conductive polymer like this PEG network could help create:

- flexible batteries

- safer batteries

- wearable energy storage devices

- stretchable electronics

Cai’s team is continuing to explore how this material might reshape battery engineering.

How UV Shaping Allows High-Complexity 3D Structures

Another impressive part of this breakthrough is the design versatility.

Because polymerization is driven by UV exposure, researchers can control the structure simply by shaping or patterning the UV light. Huang explained that this allows the creation of intricate geometries, with:

- stiff regions

- soft regions

- variable thicknesses

- interlocking structures

- internal channels

- multi-phase materials

All of these features are essential for engineering functional synthetic organs, complex biomedical devices, and new types of materials where mechanical performance can be “encoded” at the molecular level.

What This Means for the Future of 3D-Printable Biomaterials

This breakthrough demonstrates that PEG—one of the most widely used biomaterials in the world—still has unexplored potential. By shifting from traditional linear structures to a bottlebrush network, researchers have effectively given PEG a new life.

Several long-term implications include:

- Realistic artificial organs may become possible if scaffolds can be printed to match the flexibility of real tissue.

- Drug-delivery systems may become safer and more efficient with materials that don’t break under strain.

- Next-generation batteries may benefit from flexible, durable solid-state electrolytes.

- Multi-material 3D printing may allow fabricating entire devices in a single manufacturing step.

This study is early-stage, but the potential impact across medicine, biotechnology, and energy storage is enormous.

Additional Background: Why PEG Is So Widely Used in Biomedical Science

Since the article revolves around PEG, it’s worth understanding why PEG already dominates biomedical applications.

PEG is widely used because it is:

- non-toxic

- water-soluble

- compatible with living cells

- chemically stable

- low-cost

- FDA-approved in many forms

PEG appears in drug formulations, hydrogels, medical coatings, implants, cryoprotectants, and tissue-engineering scaffolds. Its main weakness has always been mechanical fragility—especially in dry or semi-dry states.

This new research directly solves that limitation, which is why it is being regarded as such a promising advancement.

Additional Background: What Bottlebrush Polymers Are

Bottlebrush polymers have gained attention in materials science because their unique structure offers:

- low entanglement

- tunable stiffness

- high stretchability

- predictable mechanical response

- customizable side-chain chemistry

They can be engineered to be soft like tissues, rigid like plastics, or anything in between.

Cai’s lab had previously developed extremely strong bottlebrush-based synthetic polymers, and this new work shows how that architecture can be adapted to create multiple forms of PEG networks—both in hydrogel (wet) and elastomer (dry) states.

This adaptability is one reason bottlebrush polymers are considered a powerful platform for designing next-generation materials.

Research Reference

Additive Manufacturing of Molecular Architecture Encoded Stretchable Polyethylene Glycol Hydrogels and Elastomers

https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202512806