A Breakthrough Non-Contact Fentanyl Detection Method Promises Safer Tools for First Responders

Scientists from the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) and Florida International University’s Global Forensic and Justice Center (FIU-GFJC) have unveiled a promising new way to detect trace amounts of fentanyl without ever touching the drug itself.

This development matters because fentanyl is not only extremely potent—roughly 50 times stronger than heroin—but even tiny amounts can pose a risk to law enforcement officers, forensic teams, customs officials, and emergency responders who often encounter unknown substances in the field. The team’s work focuses on harnessing advanced materials, handheld detection tools, and vapor-based chemical signatures to make the process faster, safer, and significantly more reliable.

What makes this achievement stand out is its emphasis on non-contact detection. Instead of testing a powder sample directly, the method detects a chemical vapor that fentanyl naturally emits as it breaks down. This signature molecule is called N-phenylpropanamide (NPPA), and it acts like a unique fingerprint floating in the air near fentanyl-containing materials. By focusing on NPPA vapors rather than the drug itself, the research team has created a safer approach that avoids accidental exposure—something that has long been a major concern among first responders.

How NPPA Became the Key to Detecting Fentanyl in the Air

Fentanyl has an extremely low vapor pressure, meaning it doesn’t easily evaporate. For years this made air-based detection nearly impossible. Traditional methods usually rely on swabs, direct sample collection, or destructive chemical processing. All of these require physical contact and carry some degree of risk.

The NRL–FIU team solved this by targeting NPPA, a small by-product that fentanyl releases into the air during natural degradation. Even though this molecule is emitted only in trace amounts, it offers a detectable and consistent marker.

To verify that NPPA was reliable enough for field use, researchers used Solid Phase Microextraction (SPME). In simple terms, SPME uses a specialized fiber that soaks up airborne chemicals. After absorbing enough vapor, the fiber is inserted into Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS), a laboratory tool that separates and identifies chemical compounds. Through this method, scientists confirmed that NPPA is consistently emitted from fentanyl and related synthetic opioids, even when mixed with common street adulterants such as mannitol, lactose, and acetaminophen.

The SPME–GC-MS analysis established a scientific foundation: NPPA is a dependable fentanyl vapor marker. But the challenge remained—how do you detect it quickly and safely outside a laboratory?

Improving Real-World Detection With a Handheld Ion Mobility Spectrometer

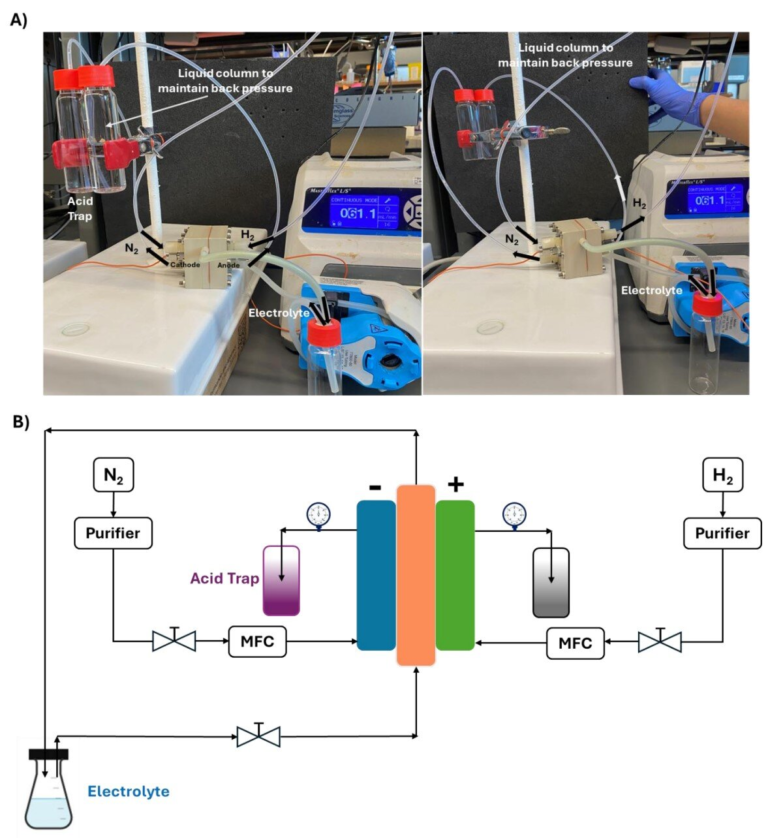

To answer that question, the team enhanced a portable Ion Mobility Spectrometer (IMS), a type of handheld device already familiar to many airport security operations and hazmat teams. An IMS works by measuring how charged particles drift through gas; every compound’s ions have a unique drift pattern, allowing the device to identify them.

The researchers tuned the IMS to specifically recognize NPPA even at extremely low concentrations—down to 5 nanograms (five-billionths of a gram). This level of sensitivity is crucial because fentanyl vapors exist in minuscule amounts, especially when the original material is sealed, diluted, or mixed with fillers.

Importantly, the modified IMS could distinguish NPPA from common benign substances normally found in seized drug samples. False alarms are a major issue in forensic fieldwork, so the ability to ignore harmless fillers while still detecting real fentanyl signatures increases the practical value of the system.

The Role of Silicon Nanowire Technology in Boosting Detection

Even with IMS tuning, the vapor levels are often so low that they require additional concentration. This is where the project’s most innovative component comes in: a silicon nanowire (SiNW) preconcentration array.

This miniature sensor array, coated with an acrylate-based polymer, adsorbs NPPA molecules from ambient air and then releases them in a concentrated pulse. The effect is a dramatic improvement in detection capability—as much as 14 times higher sensitivity during laboratory tests.

The nanowire structure gives the device an extremely high surface area, letting it capture far more NPPA molecules than traditional surfaces. The polymer coating ensures selectivity, meaning the device is tuned to preferentially trap fentanyl-related vapors over irrelevant airborne chemicals.

Another important accomplishment is that the SiNW array maintains its performance even in the presence of typical street-level adulterants. Fentanyl rarely appears in pure form when seized by authorities, so testing the system against real, messy, unrefined samples was crucial.

Confirmed Results From Real Seized Samples

Laboratories at the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and Maryland State Police supplied actual seized fentanyl materials—both pure and heavily adulterated. The NPPA vapor detection worked on all samples tested, verifying the method outside strictly controlled laboratory conditions.

These successful field tests support the system’s intended role as a presumptive detection tool. It won’t replace confirmatory forensic analysis, but it gives first responders and investigators a rapid warning that fentanyl is likely present.

Why Non-Contact Detection Matters So Much

The need for non-contact detection is driven by both science and safety. Fentanyl’s potency means that even 2 milligrams can be potentially lethal, particularly through inhalation or accidental dermal exposure. While accidental overdoses among trained professionals are statistically rare, anxiety among responders is widespread—and justified. Unknown powders at crime scenes, overdose sites, or border checkpoints create a constant sense of risk.

A portable, non-contact detection system reduces that stress. Responders can scan a scene, suitcase, or suspicious container without touching anything. This increases safety, saves time, and reduces the need for specialized hazmat procedures in routine operations.

Beyond fentanyl itself, the approach may eventually expand to other synthetic opioids or emerging designer drugs with similar vapor-based signatures. As drug chemistry continues to evolve, having flexible, vapor-based detection tools will become even more important.

A Look at Future Development

The researchers aim to develop a full working prototype of the silicon-nanowire-enhanced IMS system by the end of 2026. If successful, the device could be deployed in law enforcement agencies, customs checkpoints, emergency response units, and even military settings where fentanyl might be encountered as a chemical threat.

The project aligns with broader national efforts to reduce risks associated with synthetic opioids, improve forensic technologies, and equip responders with safer, smarter tools. The NRL–FIU collaboration also shows how combining materials science, analytical chemistry, and forensic innovation can produce practical solutions for real-world problems.

Understanding Fentanyl and Its Global Impact

Since this news centers around fentanyl detection, it’s useful to understand why fentanyl poses such a challenge.

Fentanyl is a lab-created opioid originally designed for medical pain relief. Its extremely high potency means that only tiny doses are required to produce strong effects. Unfortunately, this also makes it easy for illicit manufacturers to transport, conceal, and mix into street drugs to increase potency or profit.

Some additional points about fentanyl’s broader context:

- It is responsible for a large share of overdose deaths in the United States each year.

- Illicit versions often contain unpredictable amounts of the drug.

- It is frequently mixed with heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, and counterfeit pills.

- Many synthetic analogs—sometimes called fentalogs—emerge constantly and can be even more potent.

Because fentanyl powders can be airborne or can contaminate surfaces, investigators and responders face constant uncertainty when approaching drug-related scenes. Tools that remove the need to physically handle substances help reduce exposure fears, speed up on-site decision-making, and allow better risk assessment.

Research Reference

Reference: http://www.nrl.navy.mil/