A New Injectable Hydrogel That Turns Solid at Body Temperature Could Change the Future of Bioelectronics

Researchers at the University of Delaware have developed a first-of-its-kind conductive hydrogel that can switch back and forth between a liquid and a gel simply by changing temperature. This new material is designed to work seamlessly with the human body, opening up exciting possibilities for injectable bioelectronics, wearable sensors, and removable medical devices that do not require invasive surgery.

At its core, the idea is surprisingly elegant. Imagine a material that can be injected into the body as a liquid, then solidify at body temperature to record electrical signals or deliver stimulation, and later return to a liquid form so it can be easily removed. That is exactly what this new hydrogel is capable of doing.

The research was led by Laure Kayser, assistant professor of materials science and engineering at the University of Delaware’s College of Engineering, with Vidhika Damani as the first author. Their work was published in the journal Nature Communications, marking a significant milestone in the field of soft bioelectronics.

Why This Hydrogel Is Different From Existing Materials

Traditional electronic materials used in medical devices are often metal-based and rigid. While effective, these materials are not easily degraded or removed from the body. Implanting and removing them frequently requires surgical procedures, which come with risks, recovery time, and high costs.

This new hydrogel takes a completely different approach. It is carbon-based, soft, and designed to interact more naturally with living tissue. Most importantly, it is thermo-reversible, meaning it changes its physical state based on temperature.

The hydrogel transitions from a liquid to a gel at around 35°C, which is just below normal human body temperature (37°C). As a result, it can be applied or injected while cool and fluid, then quickly solidify once it comes into contact with warm tissue. If cooled again, it reverts to a liquid and can be removed without surgery.

This reversible behavior gives the material a major advantage over conventional conductive hydrogels, which often form permanent or semi-permanent structures once implanted.

How the Material Was Created

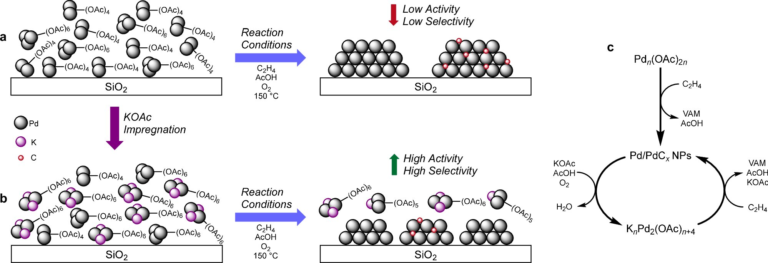

To build this unique hydrogel, the research team combined two well-known polymers in a novel way.

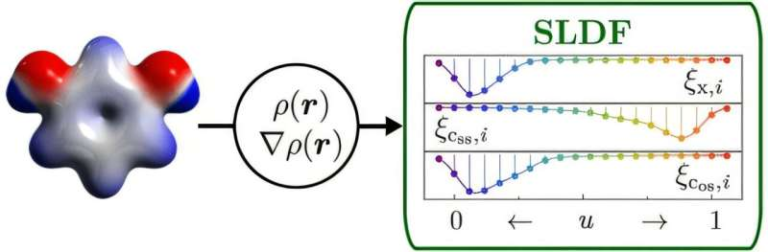

The first is PEDOT:PSS, a widely used conducting polymer known for its ability to carry electrical signals. PEDOT:PSS is already popular in bioelectronics because it can conduct both electronic signals from devices and ionic signals produced by the body.

The second component is PNIPAM, a heat-responsive polymer that becomes stiffer and more hydrophobic as temperature rises. PNIPAM is famous for its sharp response near body temperature, making it ideal for biomedical applications.

Instead of simply blending these two materials together, the researchers used a more precise method known as block copolymer synthesis. This approach chemically links the polymers at the molecular level, allowing them to self-assemble into stable structures that respond predictably to temperature changes.

After optimizing the molecular design, the team achieved a material that reliably forms a gel above 35°C while remaining fluid below that temperature.

Fast, Reliable, and Reversible Performance

One of the most impressive features of the hydrogel is how quickly it responds. Tests showed that one milliliter of the material can transition from liquid to gel in just 20 to 40 seconds. This rapid response is critical for real-world medical applications, where timing and precision matter.

The material was also tested for durability. It successfully switched between liquid and gel states at least 10 times without losing its electrical conductivity or mechanical integrity. Even after being stored as a gel for three months, it could still be converted back into a liquid simply by cooling.

Advanced microscopy and scattering experiments revealed why this behavior is so reliable. The block copolymer structure creates well-organized, self-assembled networks that allow the material to reversibly gel. Less controlled mixtures of polymers do not show the same consistent behavior.

To better understand these mechanisms, the University of Delaware team collaborated with Enrique Gomez’s laboratory at Pennsylvania State University and Darrin Pochan, a distinguished professor of materials science at UD.

Designed to Work With the Human Body

Another standout feature of the hydrogel is its ability to conduct both electronic and ionic signals. Most existing materials can do one or the other, but not both. This dual-mode conduction means the hydrogel can create a more accurate and detailed interface between electronic devices and biological tissues.

The material also adapts well to irregular or uneven surfaces, such as scar tissue or hairy skin. Pre-formed electrodes often struggle to make good contact in these situations, leading to weak or noisy signals. In contrast, this hydrogel molds itself to whatever surface it touches, improving signal quality and reliability.

Testing in Cells, Animals, and Humans

The hydrogel’s compatibility with living tissue was tested extensively. Experiments in cell cultures and rat models, conducted by collaborator Jonathan Rivnay and his team at Northwestern University, showed that the material was well-tolerated and did not cause harmful reactions.

To explore its potential as a wearable sensor, the researchers attached small samples of the gel to a human forearm and measured electrical activity as the volunteer opened and closed their fist. The results were striking. The electrical signal amplitude was reported to be 250 times stronger than that of a commercially available electrode.

This level of performance highlights the hydrogel’s promise for applications ranging from muscle monitoring to neural interfaces.

Potential Applications in Medicine and Wearable Technology

The possibilities for this material span a wide range of fields. One of the most intriguing is the idea of injectable bioelectronics. Instead of implanting rigid devices, doctors could one day inject a conductive liquid that temporarily solidifies inside the body to perform its function, then remove it without surgery.

The hydrogel could also be used in wearable devices, especially in situations where traditional electrodes struggle to maintain good contact with the skin. Its ability to conform to complex surfaces makes it ideal for long-term monitoring.

Beyond gels, Kayser’s lab is already exploring thin-film electronics made from the same material. These include organic electrochemical transistors, which are highly sensitive biosensors. Because the material responds to temperature, such devices could potentially act as both sensors and therapeutic tools. For example, detecting localized inflammation and triggering targeted drug release.

Intellectual Property and Future Research

The University of Delaware has filed a U.S. patent application for the material through its Office of Economic Innovation and Partnerships, which manages the university’s intellectual property.

Interest in the hydrogel is already global. Kayser’s lab has been shipping samples to research groups around the world, where scientists are exploring new applications for the material in their own work.

Each step forward brings researchers closer to a future where bioelectronics are soft, adaptable, reversible, and truly compatible with the human body.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-66034-x