Chemist Proposes Shared Model Proteins to Improve Reproducibility in Protein Science

Protein science has reached an interesting crossroads. The field is advancing rapidly, powered by new experimental tools, massive datasets, and artificial intelligence. At the same time, researchers across labs often struggle to compare results or reproduce findings because experiments are performed under different assumptions, protocols, and measurement standards. A new proposal by Marc Zimmer, a chemist at Connecticut College, suggests a practical way forward: the adoption of a small, shared set of model proteins that the global research community can rally around.

Zimmer lays out this idea in a recent Perspective article published in the 40th-anniversary issue of Protein Engineering, Design and Selection. His central argument is straightforward but ambitious. Just as biology was transformed by shared model organisms like fruit flies, mice, yeast, and C. elegans, protein science could benefit from formal agreement on a handful of reference proteins that serve as common benchmarks across experiments, disciplines, and even computational studies.

Why Reproducibility Remains a Challenge in Protein Science

Protein researchers work across a vast range of subfields, including biophysics, structural biology, enzymology, protein engineering, synthetic biology, and machine-learning-based protein design. While this diversity is a strength, it also creates friction. Different laboratories often use distinct experimental conditions, measurement techniques, and reporting formats. Even when two studies examine similar proteins, comparing their results can require extensive interpretation and translation.

Zimmer points out that this problem is not due to poor science, but rather a lack of shared reference points. Without agreed-upon standards, researchers spend valuable time trying to reconcile incompatible datasets instead of building directly on one another’s work. A shared model protein system, he argues, could dramatically reduce this friction.

Learning From the Success of Model Organisms

The inspiration for this proposal comes from the history of biological research. Model organisms became powerful tools not simply because their biology is conserved, but because scientific communities coordinated around them. Researchers agreed on common strains, protocols, databases, and benchmarks. As a result, findings from one lab could be readily compared with those from another, accelerating discovery and improving reliability.

Zimmer believes protein science is now mature enough to adopt a similar framework at the molecular scale. Many proteins already serve as informal standards in specific subfields. His proposal seeks to formalize and expand this practice in a way that benefits the entire research community.

What Zimmer Means by Model Proteins

In Zimmer’s framework, model proteins are not meant to replace the study of diverse or novel proteins. Instead, they act as shared anchors. These proteins would be widely studied, deeply characterized, and paired with common benchmarks and reporting standards.

The proposal includes several key components:

- Formal identification of a small group of widely used proteins as model systems

- Shared benchmarks for structure, function, stability, and performance

- Curated, gold-standard reference datasets available to the community

- Minimal reporting requirements to ensure results are comparable and reproducible

The goal is not rigid standardization, but coordination. Researchers would still pursue their own questions, but with the option to connect their work to well-understood reference systems.

The Five Proteins Proposed as a Starting Point

Zimmer suggests beginning with five proteins that are already extensively used and studied across different areas of protein science. He emphasizes that this list is a practical starting point, not a permanent or exclusive canon.

The proposed proteins are:

- Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP)

- Lysozyme

- Hemoglobin and myoglobin

- RNase A

- Bacteriorhodopsin

Each of these proteins has a long research history, well-resolved structures, and extensive experimental data. They also span a range of protein classes, including enzymes, binding proteins, oxygen carriers, and membrane proteins.

Why GFP Is a Standout Example

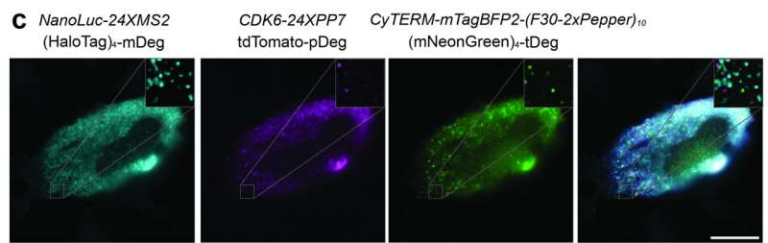

Among the proposed proteins, GFP serves as the clearest demonstration of how a model protein system can work in practice. GFP fluoresces only when it folds correctly, providing a direct and quantitative readout of protein function. This makes it uniquely useful for comparing results across organisms, experimental platforms, and laboratories.

Over decades, the scientific community has built a rich ecosystem around GFP. This includes engineered variants, standardized brightness benchmarks, plasmid libraries, and extensive public datasets. Because GFP behaves consistently across systems, researchers can directly compare findings without extensive recalibration. Zimmer presents GFP as proof that coordinated standards can emerge naturally and deliver long-term value.

The Growing Role of AI and Why Standards Matter More Than Ever

Zimmer also connects his proposal to the rapid rise of artificial intelligence in protein research. Machine-learning models are now used to predict protein structures, design new sequences, and evaluate protein function. However, these models depend heavily on training data and benchmarks.

Fluorescent proteins, including GFP, have become popular test cases for AI-driven protein design because fluorescence provides a clear indicator of success or failure. Zimmer argues that as computational tools become more influential, shared standards will be essential. Without them, comparing model performance across studies becomes just as difficult as comparing experimental results.

Community Reactions to the Proposal

The proposal has attracted attention from respected voices in the field. Nobel laureate Martin Chalfie, whose work helped establish GFP as a foundational research tool, has emphasized that the real value lies in community coordination rather than formal labels. The idea is less about naming model proteins and more about encouraging researchers to work together around shared systems.

Rita Strack, Ph.D., chief editor of Nature Biomedical Engineering, has described the proposal as overdue. She has noted that formal model proteins could strengthen benchmarking practices, improve reproducibility, and encourage broader sharing of community resources.

Next Steps Toward a Model Protein System

Zimmer outlines several practical steps for turning this idea into reality. These include convening a cross-disciplinary steering group, defining transparent criteria for selecting model proteins, and developing minimal reporting checklists that journals and researchers could adopt. Another key element would be the curation of high-quality reference datasets that researchers can rely on with confidence.

The long-term aim is efficiency. By spending less time translating between incompatible practices, protein scientists can focus more energy on discovery, innovation, and collaboration.

Why This Proposal Matters for the Future of Protein Science

Protein science underpins much of modern biology, medicine, and biotechnology. From drug development to synthetic biology and AI-driven design, the reliability of protein data matters more than ever. Zimmer’s proposal does not promise a quick fix, but it offers a clear and achievable path toward better coordination.

By agreeing on a small set of shared model proteins, the field could improve reproducibility, enhance data reuse, and make both experimental and computational results easier to compare. It is a proposal rooted in practicality, community effort, and lessons learned from decades of biological research.

As protein science continues to grow in complexity and scale, shared standards may prove to be one of the most important tools for keeping the field moving forward together.

Research paper reference:

https://doi.org/10.1093/protein/gzaf014