Chemists Reveal the Hidden Structure of the Fuzzy Coat Surrounding Tau Proteins

One of the defining biological features of Alzheimer’s disease is the buildup and clumping of a protein called Tau inside the brain. As the disease progresses, these Tau proteins form tangled fibrils, and the severity of this clumping closely tracks how advanced the condition becomes. While scientists have studied Tau for decades, a large portion of its structure has remained stubbornly mysterious—until now.

Chemists at MIT have made a major breakthrough by uncovering the structure of what researchers call the “fuzzy coat” that surrounds Tau protein fibrils. Using advanced nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, the team has shown that it is possible to study not just the rigid inner core of Tau fibrils, but also the highly dynamic, disordered outer regions that make up most of the protein. This discovery could have important implications for understanding how Tau aggregates form and how future drugs might disrupt them.

Why Tau Proteins Matter in the Brain

In healthy neurons, Tau proteins play a crucial role in stabilizing microtubules, which act like internal scaffolding and help maintain the structure and transport systems of brain cells. Under normal conditions, Tau proteins are largely unstructured, meaning they don’t fold into a fixed shape.

Problems arise when Tau becomes misfolded or chemically altered. Instead of remaining flexible and functional, Tau proteins begin sticking together, forming insoluble fibrils that accumulate inside neurons. These fibrils are a hallmark not only of Alzheimer’s disease, but also of other neurodegenerative disorders such as frontotemporal dementia and certain rare tauopathies.

For years, scientists have focused mainly on the rigid inner core of these fibrils, because that part is relatively stable and easier to study using conventional structural biology techniques. But that core represents only about 20 percent of the full Tau protein. The remaining 80 percent forms a fluctuating, mobile outer layer—the fuzzy coat.

What Exactly Is the Fuzzy Coat?

The fuzzy coat consists of disordered protein segments that wrap around the rigid core of the Tau fibril. These regions are constantly moving, bending, and changing shape, which is why they have been so difficult to analyze. Traditional methods like X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy struggle to capture structures that refuse to sit still.

Despite being overlooked for years, the fuzzy coat is believed to play a key role in how Tau fibrils interact with other molecules inside the brain. Any drug designed to break apart or prevent Tau aggregation would likely need to pass through this fuzzy outer layer before reaching the core.

How NMR Made the Difference

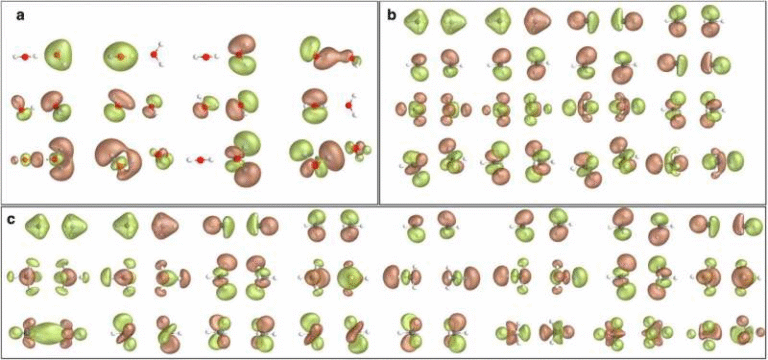

The MIT researchers developed a specialized NMR-based approach that allowed them to study the entire Tau fibril, including both rigid and flexible regions. In one of their key experiments, they selectively magnetized protons in the most rigid amino acids and then measured how long it took for that magnetization to spread to more mobile amino acids in the fuzzy coat.

By tracking this transfer, the scientists could estimate how close different regions of the protein are to each other, even when those regions are highly dynamic. They combined this with additional NMR measurements that revealed how much each segment moves, giving them a detailed picture of the protein’s internal dynamics.

This approach allowed the team to analyze the full-length Tau fibril in a way that had not been possible before.

A Burrito-Like Structure

Using their NMR data, the researchers proposed a structural model that describes the Tau fibril as resembling a burrito. At the center lies the rigid beta-sheet core, while multiple layers of the fuzzy coat wrap around it.

Tau contains roughly 10 distinct domains, and these domains fall into three broad categories based on how much they move:

- The rigid core, which is tightly packed and structurally stable

- Surrounding regions with intermediate mobility

- An outermost layer made up of highly dynamic segments

This layered organization helps explain why the fuzzy coat has been so difficult to characterize—and why it is so important.

The Surprise Role of Proline-Rich Regions

One of the most unexpected findings involved protein segments rich in the amino acid proline. These proline-rich regions are located near the rigid core in the Tau sequence and were previously assumed to be relatively immobilized.

Instead, the NMR data showed that these segments are among the most mobile parts of the fuzzy coat. The researchers believe this high mobility arises because these regions carry positive charges that repel the positively charged amino acids in the rigid core. Rather than sticking close, they are pushed outward, remaining flexible and dynamic.

This insight changes how scientists think about the spatial organization of Tau fibrils and their chemical interactions.

What This Means for Tau Propagation

Tau aggregation is thought to spread through the brain in a prion-like manner. Misfolded Tau proteins can latch onto normal Tau molecules and act as templates, forcing them to adopt the same abnormal structure.

There are two main ways new Tau proteins could attach to an existing fibril: by binding to the ends or by sticking to the sides. The fact that the fuzzy coat completely wraps around the rigid core suggests that side binding is less likely._attach to the ends of existing fibrils, making them longer over time.

This insight helps explain how Tau tangles grow and spread in neurodegenerative diseases.

Implications for Drug Development

From a therapeutic perspective, the fuzzy coat is both a challenge and an opportunity. Any small-molecule drug designed to break apart Tau fibrils or prevent their formation must be able to penetrate this dynamic outer layer.

By revealing how the fuzzy coat is organized and how it moves, this research provides valuable guidance for drug designers. Understanding which regions are most flexible, which are closer to the core, and how charges influence structure could help scientists design compounds that interact more effectively with Tau fibrils.

Additional Background: Why Disordered Proteins Are Hard to Study

Tau belongs to a broader class of proteins known as intrinsically disordered proteins. Unlike classic enzymes or structural proteins, these molecules do not adopt a single stable shape. Instead, their flexibility allows them to interact with many different partners.

This same flexibility, however, makes them prone to misfolding and aggregation, especially under stress or disease conditions. Many neurodegenerative diseases—including Parkinson’s and Huntington’s—are linked to disordered or partially disordered proteins. Advances in techniques like NMR are therefore opening new doors across multiple areas of neuroscience.

What Comes Next

The MIT team now plans to investigate whether misfolded Tau proteins taken directly from Alzheimer’s patients can be used as templates to induce normal Tau to form disease-specific fibrils. This could help explain why Tau aggregates differ between disorders and even between patients.

By combining detailed structural data with biological experiments, researchers hope to get closer to stopping Tau aggregation before it causes irreversible brain damage.

Research paper:

https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.5c18540