Chirality in Synthetic Polymers Dramatically Boosts Conductivity After Doping

A new study published in Nature Communications reports an unexpected and potentially game-changing discovery: introducing and controlling chirality in synthetic polymers can greatly enhance their electrical conductivity once the materials are chemically doped. This finding adds a fresh and promising design parameter to the field of organic electronics, where researchers are continually searching for cost-effective, flexible, and sustainable alternatives to traditional inorganic materials.

The work comes from a collaboration involving researchers at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, the University of Arizona, Georgia Tech, and North Carolina State University. The team includes Ying Diao and Joaquín Rodríguez López from Illinois, Jean-Luc Brédas from Arizona, John Reynolds from Georgia Tech, and Dali Sun from NC State. Their combined expertise spans polymer chemistry, electrochemistry, and materials science, making this an unusually comprehensive investigation into how molecular structure affects doping behavior.

At the center of the discovery is chirality, a structural feature that arises when a molecule cannot be superimposed on its mirror image. In polymers, chirality can form through persistent twisting along the chain backbone, producing helical or spiral-like structures. Chirality is already known to play a major role in biological systems and certain nanoscale technologies, but up until now, it hasn’t been viewed as a factor with meaningful impact on polymer doping efficiency. Doping—the process of introducing chemical species that donate or accept electrons—is essential for increasing conductivity in materials used for devices like diodes, transistors, and sensors.

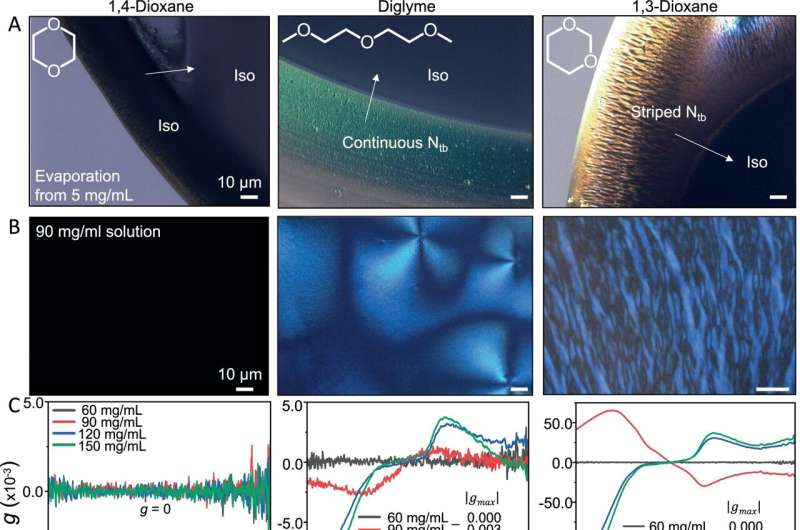

The researchers examined a polymer system called PE2-biOE2OE3, exploring how it behaves in different solvents such as 1,4-dioxane, diglyme, and 1,3-dioxane. Each solvent created distinct solution-state assembly pathways, which ultimately influenced the chirality of the final polymer film. What makes this significant is that the assembly method itself—especially when paired with solvent processing—lets the researchers control how twisted or chiral the polymer becomes. This structural tuning happens before doping and sets the stage for how the material will respond once dopants are added.

In earlier work, the same research group found that higher chirality actually reduced charge mobility. The logic was straightforward: twisting the polymer backbone localizes charges, meaning electrons or holes cannot move as freely. More localization means lower mobility, which typically leads to lower conductivity. Everything about the conventional understanding of organic semiconductors suggested that chirality should be detrimental.

But the new results overturn that expectation. After doping, more highly twisted polymers demonstrate significantly higher conductivity. This was surprising even for the scientists involved, because it indicates a fundamental shift in how chirality interacts with the doping process. Instead of hindering charge movement, chirality seems to boost the chemical reactions that occur during doping. The dopants may integrate more efficiently, or the chiral structure may stabilize the charged states better. While the research confirms the effect, the mechanism remains uncertain.

One proposed explanation relates to electron spin. Chirality is known to influence spin-selective electron transport, a phenomenon widely studied under the umbrella of chiral-induced spin selectivity (CISS). In CISS, electrons with a certain spin orientation move more efficiently through chiral systems. If doping reactions are sensitive to spin orientation—and some chemical processes are—then the presence of chirality could accelerate or strengthen these reactions, improving doping efficiency and ultimately enhancing conductivity. It’s still a hypothesis, but it fits with established observations in spin-dependent chemistry.

Another possibility is that chirality affects molecular packing and nanoscale order. Chiral polymers often assemble into structures with unique symmetry and orientation. These arrangements may facilitate better pathways for charge transfer or improve interactions between the polymer chains and dopant molecules. Enhanced crystallinity or more favorable packing motifs could be playing a role.

The team emphasizes that more work is needed to understand the mechanism. The discovery opens the door to designing materials where chirality becomes a tunable engineering parameter, but moving from laboratory findings to practical devices requires deeper understanding and replication across diverse polymer systems.

To help readers unfamiliar with chirality in materials science, it’s useful to zoom out. Chirality shows up across chemistry and biology, from amino acids to pharmaceuticals to nanomaterials. In electronics, chiral molecules have recently become interesting because they can filter electrons based on spin, which could lead to low-power spintronic devices. In polymers, chirality can arise during synthesis or assembly, and controlling it has been a challenge due to the complex ways polymer chains interact. The current study demonstrates that manipulating chirality through processing—specifically through solvent choice and controlled film formation—can make a measurable difference in electronic performance.

Doping, the other core concept here, is foundational to semiconductor technology. In inorganic semiconductors like silicon, doping is routine and well understood. But in polymer semiconductors, doping is more complicated because the polymer chains are flexible, their packing varies, and the dopants must interact with the polymer at a molecular level. Anything that alters how easily dopants can insert themselves or how effectively charge can delocalize after doping has a major impact on performance. That’s why discovering that chirality strongly modulates doping is a significant breakthrough: it offers a new way to improve conductivity without changing the polymer chemistry itself.

The research also matters because synthetic polymers present a more sustainable alternative to expensive and unsustainable minerals often used in electronics. They’re lightweight, flexible, and can potentially be produced at scale with lower environmental impact. If chirality-engineered polymers can be optimized for real devices, applications could include flexible displays, wearables, soft robotics, disposable sensors, and organic transistors.

Still, the scientists caution that practical applications are not immediate. They need to verify whether chirality affects all dopant types in the same way, whether the effect scales in larger device structures, and how stable the chiral features remain over time. There is also interest in exploring whether the concept extends to optoelectronic properties such as photoluminescence, energy transfer, or solar cell efficiency.

Beyond the specifics of this study, chirality and doping are part of a much broader landscape of polymer semiconductor research. Scientists continue to experiment with new backbone structures, side chains, doping agents, and assembly techniques. The fact that something as subtle as supramolecular chirality can strongly influence performance shows how sensitive and tunable polymer systems really are. Each new discovery helps push organic electronics closer to mainstream, high-performance applications.

For now, the key takeaway is simple: twisted polymer structures, once thought to hinder electronic behavior, can dramatically enhance conductivity when doped, and this unexpected effect may reshape how next-generation polymer semiconductors are designed.

Research Paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-62915-3