Enhancing Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials Makes Advanced Materials Modeling More Accurate and Accessible

Machine learning has been steadily reshaping scientific research for years, and computational materials science is one of the areas where its impact is becoming especially clear. A new study published in Nature Communications (2025) introduces a major step forward in how scientists model materials at the atomic level. Researchers from EPFL (École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne) have developed a new machine-learning interatomic potential that is not only more accurate but also far more accessible than many existing approaches.

Interatomic potentials are mathematical models that describe how atoms interact with one another. They are essential for simulating materials, predicting their stability, and understanding properties such as conductivity, melting points, and phase changes. Traditional quantum-mechanical calculations are extremely accurate, but they are also computationally expensive. Machine learning has helped bridge this gap by producing fast, approximate models that retain much of the accuracy of quantum methods. However, this field still faces several persistent challenges.

Why Existing Machine-Learning Interatomic Potentials Fall Short

Early machine-learning interatomic potentials, often called first-generation MLIPs, were designed for specific materials. Each system required careful tuning and deep chemical expertise, making the approach powerful but limited in scope. To overcome this, researchers later developed general-purpose or “universal” MLIPs, intended to work across many chemical systems with minimal adjustment.

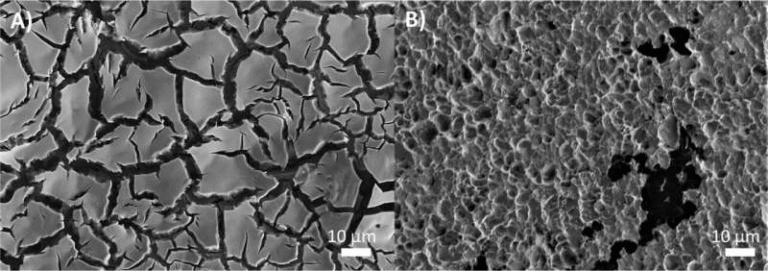

In practice, these universal models turned out to be less universal than hoped. The main issue was training data. Most available datasets came from large materials databases such as the Materials Project, which focus heavily on stable bulk materials with ideal crystal lattices. While valuable, these datasets do not adequately represent the messy, real-world scenarios scientists care about, such as surfaces, defects, adsorption, phase transitions, and molecular systems.

As one of the study’s authors explains, the community reached a point where strong models existed, but the data needed to train them properly did not. Without diverse and representative datasets, even the most advanced neural networks struggle to generalize.

Introducing PET-MAD and the MAD Dataset

The new study addresses this problem head-on with two major contributions: a new dataset and a new model architecture.

The dataset, called Massive Atomistic Diversity (MAD), contains 95,595 atomic structures spanning 85 chemical elements. It covers an unusually broad range of material types, including inorganic solids, organic compounds, molecular systems, nanoclusters, surfaces, and bulk structures. This diversity is critical for training models that can genuinely generalize across chemical space.

A key strength of MAD is consistency. Instead of combining data from multiple sources with different assumptions and computational settings, the researchers recalculated energies and atomic forces using a single, consistent density functional theory (DFT) framework. This makes the dataset more compact, information-dense, and efficient for machine-learning training.

Importantly, the MAD dataset is freely available through the Materials Cloud archive, making it a resource for the broader scientific community rather than a closed, proprietary database.

A Different Approach to Neural Network Design

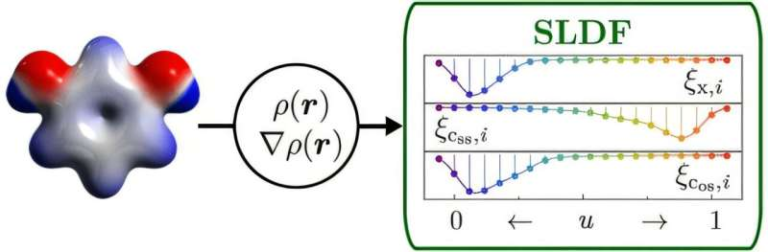

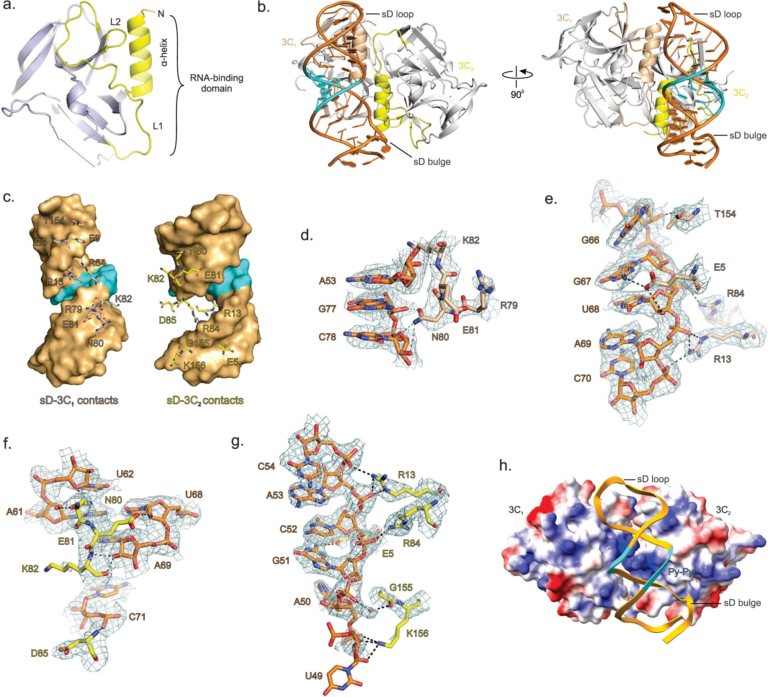

Alongside the dataset, the researchers developed a new model called PET-MAD, built on an original Point-Edge Transformer (PET) neural network architecture. Traditionally, MLIPs have relied heavily on embedding physical and chemical knowledge directly into their design. This includes enforcing symmetries, such as ensuring that a molecule’s energy does not change if it is rotated in space.

PET-MAD takes a different route. Instead of hard-coding these rules, the model is designed to learn symmetries during training. While this means the predictions are not mathematically perfect with respect to orientation, the deviations are so small that they do not affect real simulations. The benefit is a model that is faster, simpler, and more flexible than many existing universal MLIPs.

This design choice reflects a broader trend in machine learning: letting data and training guide the model’s behavior, rather than constraining it too tightly from the start.

How Well Does PET-MAD Perform?

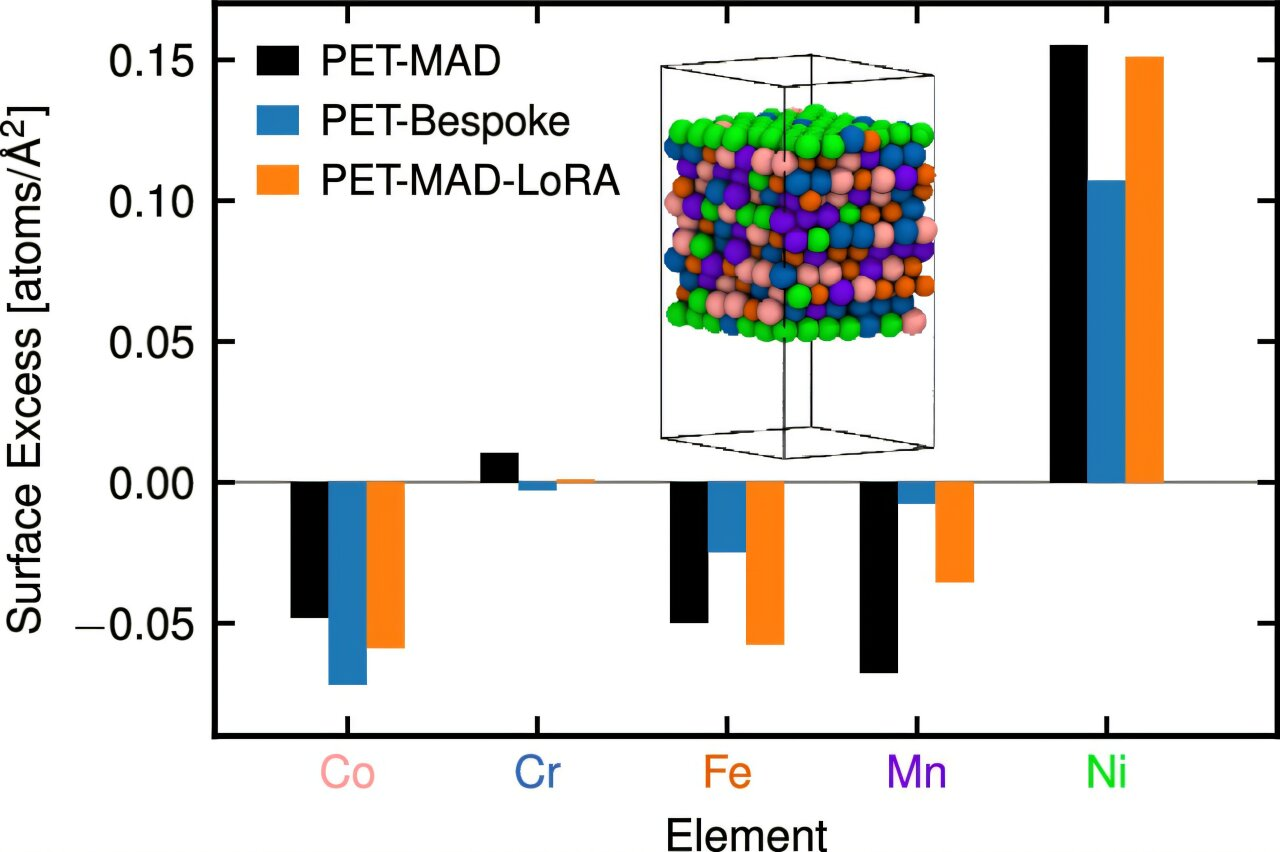

To test PET-MAD’s capabilities, the researchers ran six detailed case studies, each representing a different class of materials problem. They compared PET-MAD’s predictions with those from specialized models trained specifically for each task.

In most cases, PET-MAD achieved comparable accuracy without any system-specific fine-tuning. This is significant, because specialized models often require weeks or months of careful optimization. PET-MAD, by contrast, can be applied out of the box.

Some of the most notable demonstrations include:

- Ionic transport in lithium thiophosphate, a key material class for solid-state batteries. PET-MAD can screen large numbers of electrolyte materials and estimate ionic conductivity efficiently.

- Melting point prediction for gallium arsenide, highlighting the model’s ability to handle phase transitions, a notoriously difficult problem in materials modeling.

- Quantum nuclear effects on NMR chemical shielding in organic crystals, showing that PET-MAD can bridge the gap between traditional materials science and molecular-scale chemistry.

These examples span everything from energy materials to spectroscopy, underscoring the model’s versatility.

Why Accessibility Matters

One of the most important implications of PET-MAD is its cost efficiency. Many recent universal MLIPs have been trained on hundreds of millions of structures, requiring enormous computational resources that are out of reach for most academic labs. PET-MAD demonstrates that careful dataset design can dramatically reduce training costs without sacrificing accuracy or transferability.

This makes advanced materials simulations accessible to small research groups and institutions with limited budgets, potentially democratizing a field that has increasingly favored well-funded labs with access to massive computing clusters.

Current Limitations and What Comes Next

Despite its strengths, PET-MAD is not the final word in universal interatomic potentials. The model relies on relatively simple electronic-structure approximations, and future versions could benefit from more accurate DFT functionals. The current implementation also focuses primarily on short-range interactions, with plans to better incorporate long-range effects such as electrostatics.

Expanding the dataset further to include even more material classes and extreme conditions is another clear direction for future work.

Understanding Machine-Learning Interatomic Potentials

For readers new to the topic, MLIPs are a critical tool in modern materials science. They enable simulations that are thousands of times faster than direct quantum-mechanical calculations, making it possible to explore large systems and long timescales. Applications range from battery design and catalysis to semiconductors and pharmaceuticals.

The challenge has always been balancing accuracy, speed, and generality. PET-MAD represents a strong step toward achieving all three at once.

The Bigger Picture

By combining a thoughtfully constructed dataset with a flexible neural network architecture, the PET-MAD project shows that bigger is not always better. Smarter data selection and efficient modeling can deliver powerful results at a fraction of the cost.

In doing so, this work not only advances materials modeling but also sets an example for how machine learning can be applied responsibly and inclusively across scientific disciplines.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-65662-7